Paint Songs

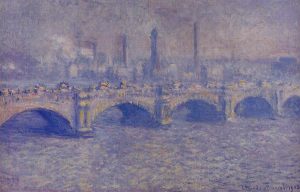

There I am: a child, a century after the final painting in Monet’s bridge series is finished, coloring butterfly masks with my mom and my brother on the cement front porch of my childhood home. My mother had printed and cut out stencils for us to scribble on in the June mountain afternoon, and we were huddled between plastic totes of crayons and faded markers. I don’t remember what mine or my brother’s mask looked like, only that my mother’s was clean and purple and well-blended, and that I thought it was the most beautiful thing I had ever seen.

There I am: a child, a century after the final painting in Monet’s bridge series is finished, coloring butterfly masks with my mom and my brother on the cement front porch of my childhood home. My mother had printed and cut out stencils for us to scribble on in the June mountain afternoon, and we were huddled between plastic totes of crayons and faded markers. I don’t remember what mine or my brother’s mask looked like, only that my mother’s was clean and purple and well-blended, and that I thought it was the most beautiful thing I had ever seen.

I never used a lot of paint when I was little. Don’t misunderstand me: I painted all the time. But some pressing minimalism or frugality—really, when I think about it: a fear of using too much— kept my art sparing and seemingly sun-faded. My strokes were light, my colors always cool. I came to prefer watercolors because of how unobtrusive they were. The pastels and gradients soothed me. I understood that I could layer what I was trying to tell someone, but I couldn’t fix spilled paint. I was coloring lightly while my brother and friends broke crayons and pencil nibs to cover fridge doors with fearless saturation. I was holding my breath. I only realized this much later. You have to remember—the impressionists tell you to look at things from a distance.