Racking-up Signposts

Grandma Walters’s souvenir spoons hung on a three-tiered spoon rack in a nook next to her kitchen hutch while I was growing up. The spoon rack consisted of three horizontal 1x1x15 inch pieces of wood on a 15×15 inch back panel with additional wood framing each side.

When I visited the farm as a child and wasn’t busy playing with my cousins and sisters, I’d occasionally climb on top of the Z-shaped metal stool with an orange vinyl-covered cushion stored underneath the spoon rack to order the spoons alphabetically by state. I apparently had no concern about whether my grandma had arranged them in a particular way, though if she had, she never scolded me for rearranging them to my liking. However, given that I remember organizing the spoons multiple times, someone else must have rearranged them too.

My process was straightforward and logic-driven: take all the spoons off the spoon rack, lay them out on the nearby kitchen table to sort them alphabetically, and then place them back on the spoon rack. The final step became an issue when I realized the spoon rack didn’t have fifty slots for all fifty states—it only had thirty slots (ten cavities per row), and though she didn’t have a spoon for every state, she did have multiples of some states. I compromised by pairing spoons from the same state and pairing similarly sized/shaped spoons ordered next to one another as needed.

One time, after finally arranging the souvenirs to a standard I could live with, I announced, “There, Grandma! Your spoons are organized!”

As she walked over from the stove, to survey my handiwork I assumed, she off-handedly remarked, “Oh, I have some more in here, honey-girl!” and pulled a glass filled with additional souvenir spoons out of the hutch.

I sighed and resigned myself to the work ahead.

My compulsive organization has a long history. When I was as young as eight, I’d pull out the fresh laundry my dad had put in my dresser drawers, refold them, and arrange them in the drawer to my liking. To this day, I am particular about having things organized—my husband, Ben, curses my knowingness: “You can tell if a cereal box is moved two inches to the right!”—and my spoon rack today follows the same ordering system I implemented on my grandmother’s.

…

I started collecting state souvenir spoons when I was 21. Ben and I had decided to go camping at Itasca State Park after he had been horrified to learn that I had never been camping: “How can you call yourself a Minnesotan?”

“My grandparents have a cabin on a lake in a tiny town in northern Minnesota that I’ve visited multiple times nearly every year of my life” I huffed. “It doesn’t get much more Minnesotan than that!”

Indeed, the summer I was born, my parents dipped me in the cabin’s lake off the side of the boat. The cabin itself is around 450 square-feet that we cram ten or more people into for sleeping purposes each summer. The furnishings are all odd cast-offs from various home updates and garage sales. Many are still the originals placed there when my grandparents bought the cabin in 1970, including the heavy, yellow Formica and chrome chairs and expandable table from the 50s. It is not a lake house.

Acknowledging my experience, but still unsatisfied I had never slept outdoors, Ben borrowed a tent from his parents, and we gathered food, bug spray, outdoor clothing, sleeping bags, and other essentials before setting off to our remote campsite.

While biking around the trails at the park, we stopped in the Jacob V. Bower Visitor Center to view the displays and considered the souvenirs available in the gift shop as we were leaving. As I rotated a rack of magnets, pens, keychains, and postcards, a flash of silver caught my eye.

“What’d you find?” Ben asked when I walked up to the cash register.

“A souvenir spoon!” I replied as I handed him the five inches of detailed metal with an Itasca State Park sticker on the handle.

…

Seven years later, my souvenir collection contains 22 spoons, but I hope to collect one from all fifty states. Twenty spoons are from states I have travelled to—I am particular on this point. I only collect them for places I have visited and done something significant in, i.e., around five years ago, Ben and I road-tripped from Minnesota to Colorado and back. Spoons from Iowa (my parents lived there), Missouri (my parents now live there), Kansas (my parents lived there), Colorado (we visited a variety of places near Denver), South Dakota (we visited the Black Hills), North Dakota (Fargo is the sister-city of Moorhead where Ben and I met), and Minnesota (hello, Itasca State Park) hang on my spoon rack. However, I didn’t buy a spoon in Wyoming since we merely drove through a corner of it.

Two spoons were kindly gifted to me by my sister, Amanda, after she travelled to Texas and Oklahoma on a Students Today Leaders Forever trip in college. But, as I have not yet travelled to those states, they are separated from the rest of the collection by a 45thwedding anniversary spoon passed down to me by a great-grandmother. Ben and I haven’t quite hit that mark as we got married just last year, so it serves as a clear boundary between the two sets of state souvenir spoons.

As I look at my collection, the similarities and the differences among them draw my attention. The spoons are usually silver colored, though two of mine (Illinois and South Dakota) are gold colored and the exception to the rule. They typically come in two lengths: three inches or five inches, plus any additional adornment on the finial (the end of the handle). Most commonly, the finial denotes the state or a specific location within the state via a sticker or a plate within a metal design, though the bowl of the spoon may also have words, images, or an outline of the state etched into it. Some spoons have unique finials, such as my Missouri spoon that is shaped like the skyline of Kansas City or my Hawai’i spoon with silver sea turtles and the Hawaiian Islands raised in a painted blue circle with silver trim. Additionally, some have a charm that dangles in a circle underneath the top decal, such as the Space Needle charm on my Washington spoon.

Some of my most unique spoons include my North Dakota spoon, which is real plated silver and quite tarnished. It has the state name engraved along the neck and the years 1889-1989 engraved diagonally in the bowl to commemorate the centennial denoted in its finial. I inherited it from a great-grandmother, who obtained it while visiting relatives there. I bought my Colorado spoon at the Denver Mint’s gift shop, and it has a blackened paisley print along the neck and clear crystals around the circular plate of the finial.

My Massachusetts spoon was purchased quickly at Boston’s airport in a gift shop, and it may be my most disappointing piece. The finial is ovular with the Old North Church emerging, while Paul Revere riding a horse along with the word Boston are raised from the bowl. Despite common and satisfactory features, the metal is what disappoints me—it is a matte metal that looks handmade and as if it is painted silver. Some may argue that the metal makes the souvenir unique among my collection, but I prefer uniform, stamped shiny metal among my spoons, despite their individual distinctive features. As I recall, I could not find a spoon fitting my preferences in Boston, so I purchased the one I now have to avoid the risk of not buying one at all—and indeed, I didn’t see any others on our short trip. So, I have a spoon from Massachusetts.

…

I’m keen to only purchase spoons from places I’ve been because I see them as a figurative map on the wall with colored pins inserted where the owner has visited. They are tokens that invoke stories about travels. They are tangible evidence of memories. As I’ve asked my grandpa, dad, aunts, uncles, and cousins about Grandma’s spoons, their faces have lit up in remembrance of the trips they were part of and stories they were told about the travels.

“Your grandpa drove their motorhome through Times Square!” my dad laughed.

“You know they drove that motorhome up where they weren’t supposed to in Yellowstone,” my aunt, Betty, snickered. “He had to back that motorhome down the edge of a mountain.”

“I remember looking through Grandpa’s eight-tracks when we went with them out west,” my cousin, Jason, grinned. “Country-western and gospel—nothing I was interested in.”

I look at my spoon from Oregon and remember renting a car with two friends and driving from Portland, where we were presenting at a conference, to Cannon Beach to put our feet in the Pacific Ocean and see Haystack Rock. I pick up my Kentucky spoon and recall the grind of a long week of contract work, but also the pleasure of making new friends, trying new food, and visiting Churchill Downs.

Sure, some I have bought in retrospect from an initial visit, like my Iowa, South Dakota, and Wisconsin spoons, but they still represent a life lived and a continent explored. I couldn’t place the first time I travelled to Wisconsin and Iowa if I tried, given that I grew up in southeastern Minnesota, approximately eleven miles from the Iowa border and 125 miles from Wisconsin. But I do remember going to Lake Okoboji in Iowa on a boating trip with my family when I was around ten, just as I recall driving to Madison, Wisconsin to buy a car with Ben in my twenties and anxiously watching the grey-green sky for hail as we drove home. My Wisconsin spoon was bought in an antique shop in Duluth. I purchased my Iowa and South Dakota spoons when Ben and I visited the states on a road trip, though I had visited the Black Hills in my teens with my family. So, ideally, I buy the spoons when I initially visit, but when that’s not possible, or not considered, I look for new adventures to obtain them.

When Ben and I recently visited New Hampshire for a friend’s wedding, we didn’t encounter any gift shops or gas stations selling the spoons. I was so disappointed we hadn’t found a spoon that I ordered one off of Amazon when we arrived home. In retrospect, I wish I’d asked my friend to find one for me, but not wanting to be a bother, I took the easy route. The spoon’s arrival was anti-climactic and disappointing. There’s something about the hunt of finding them that is essential to my collecting experience.

One may ask, how did my grandma accumulate all of her spoons if she and my grandpa were farmers? Well, when my grandpa retired from farming and the local bar he subsequently bought and sold in his late forties, he and my grandma bought a 1977 GMC Midas motorhome that they used to travel around the continental United States. Along the way, my grandma, a perpetual collector of antiques and dishes, bought her spoons. They took a three-week trip out to the East Coast to see the monuments and museums, in addition to trips to Florida, Texas, Tennessee, Las Vegas, California, and Yellowstone. Their travels were helped by my family living in Nebraska for a few years and my uncle, Jeff, moving to Colorado. After living on a farm in southern Minnesota for her whole life, my grandma wanted to see as much of the United States as she could, and my grandpa went everywhere my grandma did after they got married when she was 19 and he was 21. They didn’t see all 50 states, but I’d like to think they saw enough for my grandma’s liking before nestling down on the farm again, my grandpa’s favorite place.

…

My sentiments and desires toward collecting the souvenir spoons are certainly grounded in the fact that my grandmother collected them. My grandma was rarely out of the kitchen for long, so as I organized her spoons as a child, I’d ask her about when she got certain ones, and she’d tell me about the trip to that state. Sometimes they were labeled with a place I couldn’t connect to a state (for example, my Itasca State Park spoon has no mention of Minnesota on it), so I’d ask her where the spoon came from. Occasionally, she’d have to come over and look at the souvenir herself before closing her eyes, as if to place herself at the location in her mind’s eye, before telling me where she bought it.

Her kitchen was the location of endless conversations and card games, as well as numerous memorable meals. Along with the traditional fixings, Thanksgiving meant her signature, slightly lumpy mashed potatoes; pumpkin pie doused in whipped cream; raspberry Jell-O with garden raspberries immersed; and two dozen or more devilled eggs. Christmas Eve meant chili and oyster stew with aunts, uncles, and cousins crammed around the kitchen and random card tables. Afterward, as we digested, we’d play rummy, tic, 500, or if you could partner off from the large group, cribbage.

In early November, during my senior year of high school, my family found out that Grandma Walters had colon cancer, and the prognosis wasn’t good. She started the process of chemotherapy but stopped and moved to hospice after deciding she didn’t want to live the remainder of her life in misery from its effects. I was conscious of the necessity to record the recipes that she used no recipe cards for. However, my anticipatory grief and need for hope prevented me from acting on that awareness. She died in May, two weeks before I graduated. Her death left me searching for ways to recreate that kitchen, both in taste and feeling.

…

In the past year, I inherited my grandmother’s spoon rack due in large part to my grandpa moving off the farm and into assisted living after he fell multiple times. Since my grandpa’s move, my dad and his siblings have been organizing, dispersing, and throwing out 100 years’ worth of possessions collected on the farm. My sister, Makayla, was there one weekend when they were sorting through items in the garage and out buildings, and when she saw grandma’s spoon rack in a discard pile, she pulled it out and noted that I’d want it for my spoons. It was quite dusty when I received it, and it doesn’t hang flat on the wall after being stored in a garage and thus exposed to Minnesota’s temperature changes. Nevertheless, I happily removed the flat spoon rack I’d found at an antique shop from my kitchen wall and replaced it with my grandmother’s cleaned and warped one.

Receiving my grandma’s spoon rack helped bring her presence into my kitchen, but it also made me wonder where her souvenir spoons went. I’ve since confirmed that my aunt, Debbie, my grandma’s only daughter, has them, which is fitting. I’d love to have the spoons, but I respect her privilege to them. In particular, I’d be interested in spoons from states I visited prior to beginning my collection. Many I have not visited again to be able to buy a spoon from, such as states I visited on a week-long school-organized bus trip to Washington D.C. as a high school freshman. Since my grandparents never travelled outside the continental United States, I’ll have to either visit places such as Puerto Rico again, which I travelled to on a training trip for swimming in college, search for the spoons in antique shops, which is satisfactory in its own way, or purchase them on the internet, which is particularly disappointing.

…

In addition to the souvenir spoons on my rack, there also hang four stainless steel Stanley Roberts Lancelot teaspoons, which I treasure more than all the souvenir spoons. As I’ve gotten more and more of my grandmother’s (and now mother-in-law’s) itch for antiquing, I’ve also been on the lookout for additional silverware to make a complete set, and recently picked up a matching box of six knives. They’re heftier than the spoons.

Each individual spoon is heavier than any other teaspoon I’ve held and consciously paid attention to its weight. The spoons are thick—nearly twice the depth of most spoons I’ve seen. Beyond the neck of the spoon, the handle is a honeycomb pattern with a dot in each honeycomb. There are four dots going down the center and five along each side of the center. Between the dots and the honeycomb outline, the metal has been darkened.

These four were given to me when I was in my early teens by Grandma Walters. She always had a hodgepodge of silverware sets, but these four spoons didn’t have any matching forks or knives in her silverware drawers on each side of the kitchen sink. I’d always seek out one of the spoons when I ate ice cream at the farm. I’d pull the Kemps gallon ice cream bucket out of the freezer located underneath the windows at the end of the kitchen counter, along with a glass jar filled with garden raspberries out of the fridge.

Each summer, my grandma would go out and pick ice cream buckets full of raspberries and black raspberries from the roughly 10×16 feet patch behind her garage. (If I was “helping,” more berries were making their way into my mouth than the bucket.) After rinsing the berries off inside, she’d spread them out on cookie sheets and coat them with sugar. Then, they’d be divvied up into any jars she had available and frozen.

After my ice cream turned burgundy from all the berries I dolloped on it in one of my grandma’s Anchor Hocking Fire King milk glass chili bowls, I’d grab my spoon and settle in on the couch to savor the delicious treat. I loved to take a scoop and flip the spoon’s bowl upside down in my mouth, to make sure I didn’t miss a drop. After noticing that I always pulled one of those spoons out to eat, Grandma Walters said I should take them home with me if I liked them that much, so I did.

…

I wonder what my future children will collect, if anything, how it will be influenced by the people in their life, and what it will mean to them—just as I wonder how my future children will remember the sleek concave set of silverware Ben and I received as a wedding gift, if they place any significance on the household silverware at all. They will certainly see my souvenir spoon collection in a warped spoon rack on the wall, though, and hopefully they’ll ask me about it. Maybe they’ll even create some of their own memories by acquiring some of the spoons with me.

_____________________________

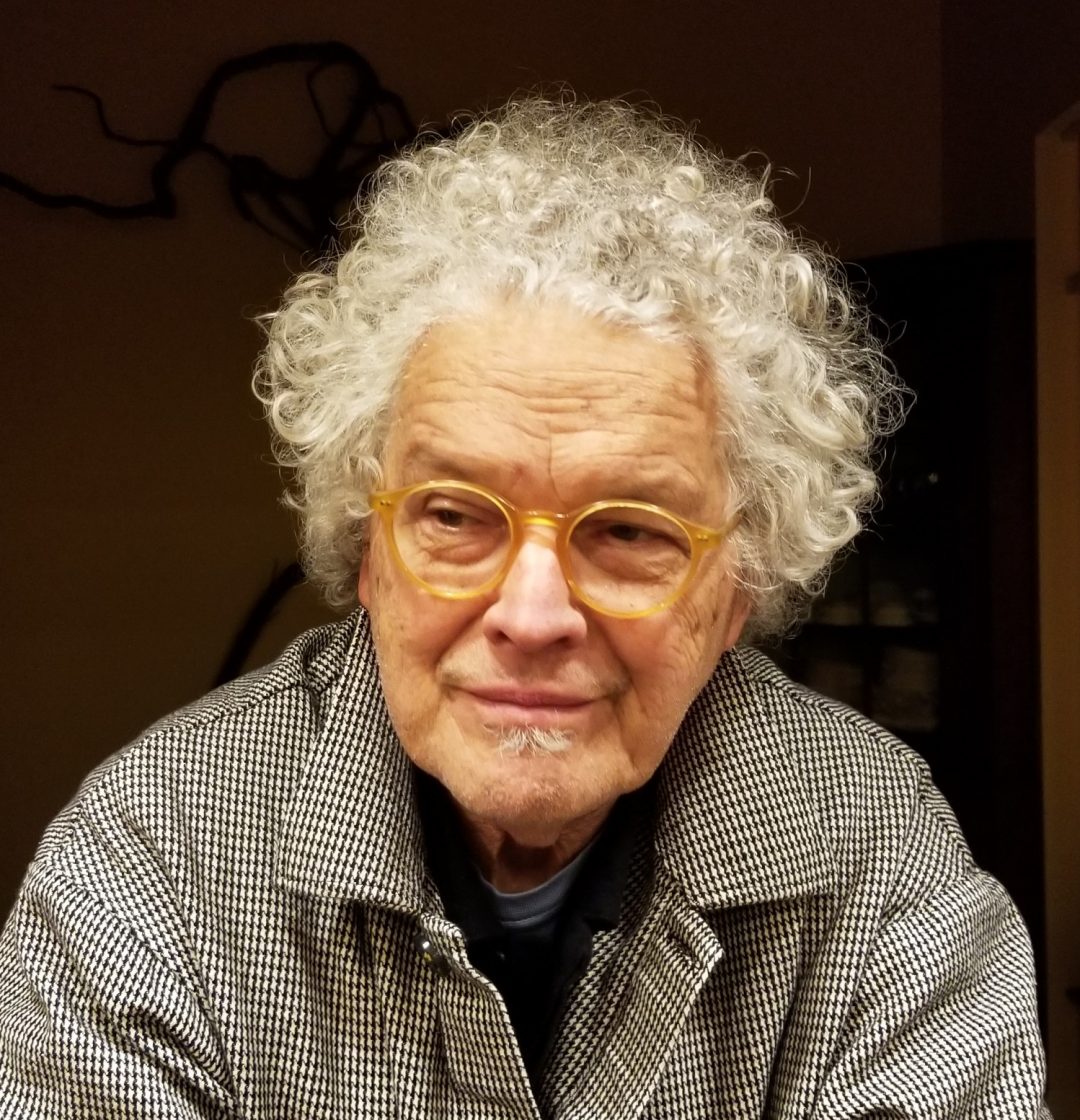

Bio: Whitney (Walters) Jacobson is an Assistant Professor at the University of Minnesota Duluth and an Assistant Editor of Split Rock Review. Her poetry and creative nonfiction have recently been published in DASH, Feminine Collective, Likely Red Press, Wanderlust-Journal, and Voice of Eve, among other publications. Visit her website at whitneywaltersjacobson.wordpress.com.