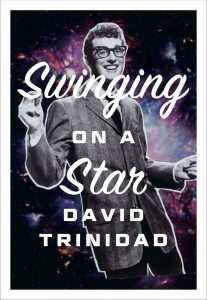

The occasion of “Ode to Buddy Holly,” which occupies the entire second part of the new collection Swinging on a Star, is a journey by David Trinidad to Lubbock, Texas, birthplace of Charles Hardin Holley. The poem begins with a portent. When the poet was a small child, two planes collided in the air near his home in Southern California, and the burning wreckage fell on Pacoima Junior High School. Three students were killed and many others hurt. By a twist of fate, one of the school’s students, Richie Valens, was not at school that day. Like Buddy Holly, Valens would go on to top the rock and roll charts with his hit “La Bamba” (the Pacoima plane crash is the first scene in the Valens biopic of the same name), and, along with Holly, Valens would die in a plane crash in an Iowa cornfield near Clear Lake, Iowa, which would also claim the life of the Big Bopper on February 3, 1959.

The occasion of “Ode to Buddy Holly,” which occupies the entire second part of the new collection Swinging on a Star, is a journey by David Trinidad to Lubbock, Texas, birthplace of Charles Hardin Holley. The poem begins with a portent. When the poet was a small child, two planes collided in the air near his home in Southern California, and the burning wreckage fell on Pacoima Junior High School. Three students were killed and many others hurt. By a twist of fate, one of the school’s students, Richie Valens, was not at school that day. Like Buddy Holly, Valens would go on to top the rock and roll charts with his hit “La Bamba” (the Pacoima plane crash is the first scene in the Valens biopic of the same name), and, along with Holly, Valens would die in a plane crash in an Iowa cornfield near Clear Lake, Iowa, which would also claim the life of the Big Bopper on February 3, 1959.

Despite this uncanny connection to two of the most famous plane crashes of the middle twentieth century, Trinidad did not know of Holly until the song “American Pie” hit the charts in 1971. “The day the music died” lyric in the song refers to the fateful crash. Trinidad says,

From that moment on

you became

a heroic figure—

random victim

(despite your fame)

of indifferent fate,

the burgeoning artist

cruelly denied

fulfillment

of his gift.

Trinidad’s interest in Holly is rekindled years later by an invitation to give a poetry reading at Texas Tech University. He pores over the details of the musician’s life on the internet and, while in Lubbock, pays a visit to the museum and two to his gravesite.

The poem is an ode to Holly. The poet at times addresses the late musician directly and, though the poem is long, its lines are short, as though each seeks to remind the reader of a life cut short.

. . .

you strum your

1958

Fender Stratocaster

and sing

into the silver mic,

the lenses

of your black-rimmed glasses

(not yet iconic)

glinting

in the camera’s flash.

On his choice of an ode as the form of the poem, Trinidad says,

I wrote “Ode to Buddy Holly” when I was in the middle of reading Pablo Neruda’s odes (all 225 of them). It took about a year and half to read them, roughly one a day. I’d written a skinny Neruda-esque ode before (to the ’70s gay porn star Dick Fisk), so I was familiar with the form. There’s a lot of freedom in writing a long poem in short lines; its threadlike momentum pulls you along. And I love addressing poems to celebrities, having a conversation with them, their spirit. It really is an intimate engagement.

Critics are accustomed to determining the voice of the “speaker” of a poem, but “Ode to Buddy Holly” announces itself quite clearly as a lived experience of the poet, an observer who witnessed firsthand a plane crash and contemplates the physical artifacts of a life stolen by destiny.

As the poet explains,

I was inspired to the write the poem when I was asked to give a poetry reading in Lubbock, Texas, Holly’s hometown. As I prepared for the reading, I connected with Holly and his music. It’s all depicted in the poem, the journey I took, both in my life as a poet and my communing with Holly. Holly the rock star and Holly the vulnerable human being. I’ve written about my first memory—the plane crash in Pacoima, California, when I was three years old—but revisiting it in this context enabled me to make sense of it in a deeper way, one that felt poetic and spiritual. I would say that “Ode to Buddy Holly” is a poem and a work of nonfiction. It’s all autobiographical, all exactly as I lived it. It’s driven by a desire to report, to record, and also by intuition. The whole experience was like diving into a mystery.

—Ian Morris, Managing Editor

Swinging on a Star will be published by Turtle Point on October 3.