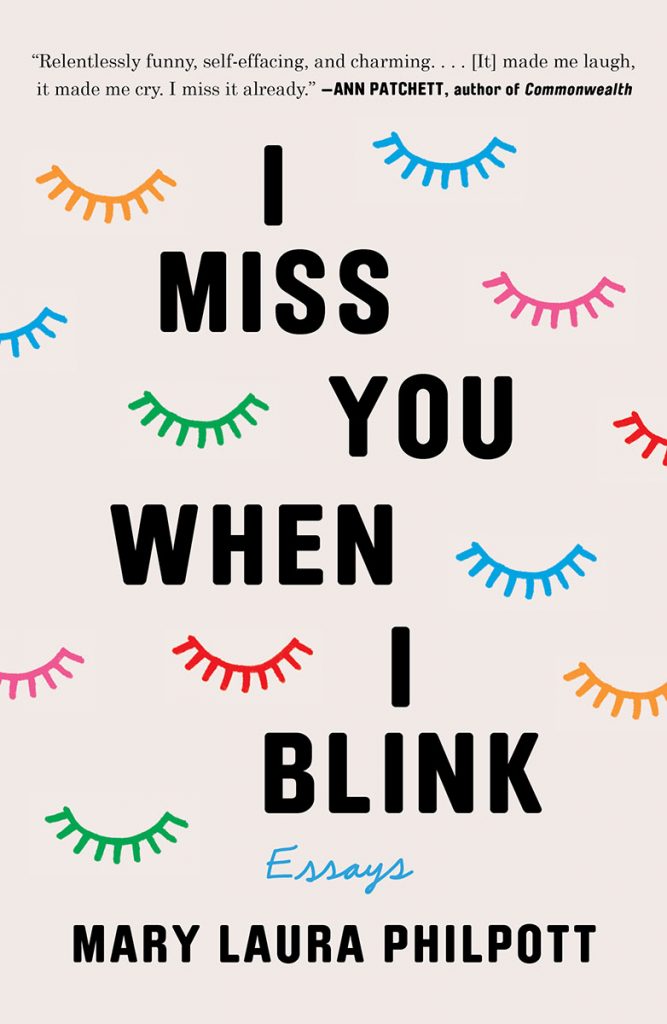

I Miss You When I Blink

Mary Laura Philpott

288 pages

Atria Books, $26.00

Mary Laura Philpott’s I Miss You When I Blink is not a self-help book, but there are so many gems about how to live one’s life in this memoir-in-essays collection that I’d like to bestow this honorary genre upon it as well. It’s funny, poignant, thought-provoking, and also a page-turner to boot. It’s easy to follow Philpott on her journey, dipping into her childhood and college years, to her twenties and thirties, and to her current world as a freelance writer, cartoonist, wife, mother, and self-admitted Type-A person.

In the book’s titular essay, Philpott reveals the meaning behind the phrase. Her six-year-old son was singing to himself, coming up with rhyming sounds for works that ended in -ink, and “I miss you when I blink” halted Philpott’s struggle to come up with tantalizing copy to describe luggage. She adopts this “go-to chorus” because it “helps her slow down and absorb each instant instead of rushing,” especially during those tiny adult identity crises. All throughout our lives we’re going through small life transitions: a new job, a new role as a parent of a teenager instead of a middle-schooler, a new phase in which you’ve outgrown friendships or relationships. Because “so many ways of being are being pitched to us—particularly to women—as either-or choices,” career or family, “a domestic goddess that cans her own strawberry jam, or a trainwreck that flaunts the wine in her coffee mug . . . pious or profane,” it’s helpful to pause and remember who she is, who she’s been.

Concepts of selfhood, identity, and the “blink” echo throughout the book as we learn about the cast of characters in Philpott’s life. In her essay “Rock You Like a Hurricane,” Philpott recounts her time learning guitar and her love of “trying on a different persona from time to time.” Specifically, she describes Halloween costumes she’s had over the years, and the “thrill to look at the mirror, blink your eyes and see the glittery eyelids of a different person looking back. It makes you think Who are you?—which is a useful question to ask yourself from time to time.” I love that Philpott has these pauses in her life—the moments where she stretches herself, interrogates herself, thinks. No matter how many times I read about how fast life moves by, especially American life, with our constant rushing and working, I still need reminders like this to look at myself and my life and make sure I’m living it the way I want to.

Philpott also describes her encounters with depression across several essays, notably in one entitled “Ungrateful Bitch.” She explores the times in her life when she missed feeling known and times when she wanted to be “unwitnessed,” especially when she was despairing but could point to no real cause. I found it profoundly moving when she plainly writes, “Unfortunately, having a fine life doesn’t exempt anyone from existential angst.” How helpful it was to read this line, how it reminded me of my own feelings of guilt when feeling down; I felt a softening toward myself. In this chapter, she reckons with the fact that her depression doesn’t have any inciting incident she can point to, no concrete trauma, but that it’s there nonetheless, and possibly even more frustrating because of it. Quotes like “One person’s more-sad doesn’t cancel out another person’s less-sad” make clear something I’ve tried myself to put into words for years.

It’s her voice that I find most powerful in this book, and her ability to laugh at herself, her foibles, her life. Her writing is funny. Entire essays made me guffaw on every other page. In the final essay, when she’s describing the lessons she’s learned in her role as an interviewer on television, she says that during filming, “you must hold the electrified posture of a startled ballerina if you want to look like you’re sitting up straight.” In “This is Not My Cat,” Philpott meditates on a recipe for “Hot Buttered Crackers.” She asks, “Why does this require a recipe? Is it gross?”

She also meditates on past conversations with other adult women, her hunger for meaningful discussion palpable but futile. Philpott writes, “I couldn’t pretend to give a shit about chicken salad any more than I could find the right moment to jump in and add to the conversation or change the subject.” I’ve been there, and I love that Philpott found a way to render this with humor and earnestness in equal measure.

Her humanity reminds me of my own, but by reading this book, I realized I might not be as Type A as I’ve originally thought. In “The Perfect Murder Weapon,” Philpott writes, “If success came in a snortable form, I’d sniff it up each nostril and rub the residue on my gums.” She jokes that despite having no murderous intentions, she still finds herself, after having watched some killer drama on TV, re-plotting a flawless murder, deeply committed to finding a way to get it perfect. She writes, “My name is Mary Laura, and I’m addicted to getting things right.” There’s a small chance that Philpott is exaggerating here, but it made me appreciate my ability to relax, take life as it comes, and even my capacity to let myself make mistakes.

It’s not an exaggeration to say this book can teach you how to live. In her essay “The Joy of Quitting,” she writes, “Deciding what you won’t have in your life is as important as deciding what you will have.” It’s a profound interrogation of the self and the mutability of it, how quickly we can change, even without realizing it. Reading it made me feel more at home with myself, and reminded me to ask questions I don’t often think about in my daily life: Who are you?

Lauren Rheaume is an essayist and the HR & Operations manager at GrubStreet. She’s been published at Boston Accent and GrubWrites. You can find her on Twitter and IG at @laurenxelissa and online at https://lauren-rheaume.com/.