Introduction: “In the Land of Fire and Ice”

When I learned the sixth NonFictioNow Conference would be held in Reykjavik, Iceland, it occurred to me that the trip would provide a perfect opportunity for a collaborative travel essay about a country that until recently was not high on tourists’ visiting lists. Who better than accomplished nonfiction writers to describe and explore this spectacular and once seemingly lonely land from outsiders’ points of view? The call for contributions went out to all conference participants, with the main guideline being that the pieces reflect some aspect of the conference or the Icelandic experience and that no submissions exceed 300 words (at least not by much).

Iceland is not so lonely anymore. Now according Conde Naste Traveler, “data from the Icelandic tourism board shows that there are officially more tourists than there are residents in the country, and the tourist number is so massive that Americans alone outnumber the Icelanders.” But if you travel the ring road around the country—as I did following the conference with my husband and two friends—traversing vast stretches between homes, villages, and gas stations, the island seems to be inhabited primarily by sheep.

During the trip, we had many adventures. My favorites included hiking a glacier (where I tumbling into a crevice and battered my knees), floating in the blue lagoon, taking a ferry to Hrisey Island where forty species of birds reside and visiting the tiny village of Seyðisfjörður nestled at the apex of a fjord. The only spots that seemed over run by tourists were in the golden circle, near Reykjavik, particularly at the famous geyser in Haukadalslaug National Park—though the number of people did not begin to rival Yellowstone where I remember from many years ago, a parade of cars inching toward Old Faithful.

As I made purchases and ate in restaurants, I felt gratified that tourism helped Iceland recover from its financial crisis between 2008 and 2011, when all of its major banks failed. That said, I was also keenly aware during most of the trip that it was a privilege for me to be there; neither my parents nor grandparents would have even considered a trip to Iceland, seemingly the land of Vikings and fearless adventurers. I was also mindful of the negative impact such a huge influx of people (visible or not) have on both the land and the economy. Several Icelanders told us how it was harder for young people to rent apartments because anyone who owned an extra place made a greater profit by renting it to tourists as an Airbnb than on a monthly basis to residents. (We stayed in several Airbnb’s; at one of these, the older Icelandic proprietors seemed delighted in their newfound source of income.) A waiter, who was considering moving to Chicago where we live, mentioned how he resented tourists because of what they were doing to the environment, citing a natural landmark that had been trampled into oblivion by tourists. I didn’t catch the name of the polysyllable place and was too embarrassed to ask him to repeat it, knowing I still probably would not have been able to pronounce it.

Travel is a dilemma. I know visitors influence traditions, the economy, and the environment. Yet, I also believe travel—to actually experience other countries—is one of the best ways to attempt to understand and appreciate other cultures, as long as we always respect them. I hope the following collaborative essay gives readers a sense of this spectacular country, as well as the conference, from a variety of perspectives an assortment of voices.

Curating the essay is one of those happy times when the results surpassed my expectations. Many of the accepted pieces seemed to fit together almost organically as they arrived in my inbox. All of them present either idiosyncratic observations and/ or exquisite writing styles (or images), resulting in a stunning collage. However, I can no longer call it a travel essay since segment #11 was written by an Icelander. I want to thank all of the writers for their generosity of spirit and their courage in contributing to an experiment that had a deadline just weeks following the conference and whose results they had little control over.

—Garnett Kilberg Cohen, Coeditor, Punctuate. A Nonfiction Magazine (with Re’Lynn Hansen),

July 2017

In the Land of Fire and Ice

1 On Likeness

Shortly after arriving in Iceland, I described the place as a rugged version of Ireland, another European island country in the North Atlantic. Their names share all but one letter. Iceland’s chilly, overcast, drizzly weather struck me as reminiscent of my ancestors’ home. The greenery, though not ubiquitous, is vibrant. While many houses and shops in Reykjavik are constructed of corrugated metal, Iceland shares a history of turf houses with Ireland. Many Icelanders speak English fluently. The two countries value reading and writers, a reason four hundred of us gathered in Reykjavik.

Quickly, Iceland felt less like another place—less familiar as it became more familiar—and I felt uncomfortable with my initial urge to compare it with somewhere. Within days, a fellow writer compared Iceland to the moon, and I bought a T-shirt that says, “Don’t go to the moon. Visit Iceland.” Neil Armstrong, humanity’s first moonwalker, called the optical properties on the moon “quite peculiar.” Buzz Aldrin, the second person to step onto the surface of another celestial body, called the moon “magnificent desolation.” Of course.

But Iceland is not much like the dust-covered moon, which has one-sixth the gravity and four times the curvature of our planet. Only twelve people could make that comparison with firsthand knowledge. For the rest of us—for any of us, grappling with the unfamiliar—likeness is imagination. Iceland is utterly earthly, a place where pieces of the earth’s crust come together, where the heat of this planet is palpable.

Iceland is active volcanoes, spouting geysers, and moss-covered lava fields. One of its islands is my age. Likeness delineates variation and departure, and vice versa. Seeing—seeking—likeness acknowledges both the distinction and the slippage between here and there. We seek a here there, a there here, a there there.

2 Fear of the Unexpected

The way the hooves strike the earth is genetically distinct. Our horses spook at the sight of a blue nylon tent, illegally pitched. Even vacant, it is perceived as dangerous. Our guide explains that the horses have never seen such a shape—as alien to them as the vast volcanic stretch is to us.

3 Shipwreck

“Please do not disturb the remains,” reads the sign at the head of the beach at Drjupalonssandur. Across the dark strand, shapes of twisted iron lodge between the rocks, half buried in sand; all that remains of the Epine GY7, a British trawler that left Grimsby on the Yorkshire coast for a fishing voyage to Iceland on March 1st 1948. Twelve days later she hit rocks off the shore where we stand. Of the nineteen men on board, only 5 survived.

Garth, a sculptor, is obsessed by the weathered iron shapes and traverses the beach photographing every one he can find. According to the Wreck Report, filed in Southhampton on the 17th of September that same year, the Epine was a single screw, single deck vessel outfitted with three compasses, one Marconi echometer, a wireless transmitter and radio and other navigational aids all in working order. Sixty-nine years later, only bits of iron remain.

I walk the waterline where waves crash into a bed of polished black stones, each a voluptuous black pearl. I can’t stop looking at the waves, how they rise up white, then show a surprising blue underside, the clearest aqua blue, as if each one is a liquid glacier, before toppling down. Then the entire beach becomes music, the waves pulling and pushing the stones, which roll and clatter in a tremendous din.

When you died it was dawn. Through the hospital window, peach-colored light was filling the sky and the world went still with sudden beauty, as did your face, each wrinkle softening like a the petal of a rose.

This is the hardest part of letting you go. I won’t be able to tell you about this place, this dark fairytale landscape we’ve been traveling through. The world in all its wonder and drama.

4 Speechless

To an English-speaker’s ear, Icelandic sounds like ice—a considerable slab—is getting in the way of words in a native’s mouth. And the words, made of unfamiliar letters and surprising marks, befuddle newcomers and can’t be easily reproduced. You can’t say what street you’re on or where you’re headed, or later recommend a restaurant to a fellow traveler. “I think it starts with a kind of a D, but it doesn’t sound like that,” you mutter. You can’t tell a story that shows you’re figuring anything out, and this is especially disconcerting for writers. Since you barely sleep in the sunny night, even after plenty of drinks, you are bumbling, or maybe you mean to say humbling, it’s all humbling. The wind blunts and muffles, affirming a sense of your extraordinarily remote location. You are decidedly away, wherever and whenever the air smells so sweet. You are speechless in a new silence.

5 Police

The woman with curly hair said, “We were on a panel once. You are an ex-cop, right?” She was with a man I knew. She smoothed her hair and fluffed it again. People at conferences pretend to have a good time when their hearts are breaking. All our hearts were breaking from the election. The woman’s nose was beautiful and curved to the right before ending in a point, like the nose of Madame X in the painting by Sargent. I was seeking comfort in nature. That day I had seen baby lambs and palominos with Bowie haircuts along the roads leading out of Reykjavik. An Icelandic woman had told me, “We are against armies, and we embrace gay people.” I said, “If only I could afford a cup of coffee here.” Every drive is a drive away from sadness. I said to the woman with curly hair, “Yes, I was a cop.” I would have agreed to anything she asked. I could see myself in the uniform. The uniform invents the danger, handcuffs jingling off a back pocket, a holster hugging a hip, a hat with a shiny black visor. I wanted to walk along the shore with her, hunting beach glass. I was wounded, although no more than anyone else. Maybe a bit more self-pitying. I could see from her eyes she liked that about me. I said, “Before astronauts jetted to the moon, they walked on the moss-covered lava of Iceland. The moss takes a hundred years to mature and sometimes grows across crevices hikers fall through. Five mammal species are native here: reindeer, mice, rabbits, arctic fox, and mink.” She said, “I believe nonfiction should be factual.” We floated into the white night, past a cemetery, where women held glass jars of wine and sang a drunken song in Norwegian. She said, “Are you hungry?” I said, “I am always hungry.” I didn’t care about advancing from point A to point B.

6 Tender

D said her parents told her they remembered when there was just one black man in the whole country. And no black women or children. The Nordic House is surrounded by the University of Iceland but the Nordic librarian is wistful for the early days when it was surrounded by green. The guidebook says that hello is Soell for greeting a man and Soel for a woman, but the librarian says everyone says Hi. I have learned how to say Thank you very much. The guide book tells how to say, Stop, thief! but not how to ask for the check. It is similar to the German Rechnung. D is from Iceland and is spending the summer tagging fish with her father. They scoop them up and shoot metal in their foreheads. A slippery sole got tangled in their SUV. Soles, she says, can live for a while out of the water. She wears gloves when she works. During the war British and American soldiers outnumbered the Icelanders. The Allies wanted to stave off a Nazi invasion. All the menus are bilingual. I haven’t seen a third language. Just because it is still light out does not mean the stores stay open till midnight. D said Costco just opened, and the lines were out the door. It was heaven, she said. Food prices are high for us and high for the Icelanders. But at Costco it is cheap and so the stores around town are going to have to lower their prices, she said. There was something miniature-fernlike in my salad tonight. (Tender fresh mussels and clams, salad, bread, $45, the mussels almost too tender they were so fresh.) The greens seemed fresh. Waffles on the street, plain, are almost 600 kroner, about $6.

7 Fever Dream

Our plane chases the rising sun across the Atlantic. Neither of us sleeps. When my son turns three in one week, he will cross many milestones, such as going into the pool without me in his swim class. But we don’t have to face that yet. We go straight to the Blue Lagoon, where steam collects around his head as he latches his legs around my waist. With his floaties, he looks like an angel. He stares into my eyes with an expression of devotion (usually, he just says no a lot.) He’s psychotic with fatigue. Iceland not ice land, he says on the ride to the city through the Dr. Seuss landscape. It rock land. It lava land. There is no day there is no night, it is said about the weeks postpartum. Your baby latches on to you and wakes every two hours day and night, and so do you. You lose your outlines. He believes your body to be a part of his. In Reykjavik, I sit up with him waiting for jet lag to wear off. I have read that the sun will set at eleven and arrive at three, but I did not take into account that the four hours in between will consist of dusk and then a cruel lightening of the night sky. The child does not sleep. I, too, become psychotic with sleep deprivation. When the babysitter arrives, he says, Mommy, I very love you. He refuses the babysitter. He cries, saying, I love you so very much. I say, Love should make you happy, not sad. A week later he really does turn three. He really does go into the pool with the instructor. It is as if none of this happened. It was all a fever dream.

8 Notes on Lagoons

Lagoon: A shallow body of water protected from a larger body of water (usually the ocean) by sandbars, barrier islands, or coral reefs.

The Blue Lagoon: Manmade in 1976. 10 km from the Greenland Sea. Formed by the runoff of the Svartsengi Power Station. Maybe they were drawn to the milky blue water, or the runoff’s warmth: the Svartsengi workers started bathing in the runoff post-shift. After several dips, psoriasis seemed to disappear.

Premium: For $102 USD, you can purchase the Lagoon’s ‘most popular spa package,’ which includes the use of one bathrobe, a towel, slippers, a drink, and a reservation at the Lagoon’s restaurant. For $61, you can enter the Lagoon and use the complimentary Silica mud mask: but remember to bring your hotel’s stained towel, which you will carry home cold and damp.

Mom: Wants to talk about Trump and school gun policies and Michael Moore documentaries through her free Silica mud mask. Silenced by J: A friend who, against all of the warnings on the signs, dips her dark hair into the Lagoon and floats until she is nothing but a smear of red lipstick in turquoise. Not wearing her free Silica mud mask until after our Lagoon photos have been uploaded to Instagram.

Svartsengi Power Station: The world’s first geothermal power plant whose blue runoff fills the bathing pool of the Lagoon.

Thirteen: Number of production boreholes connected to Svartsengi.

Jón Halldór Sigurðsson: Died in his apartment on February 6, 2017, when the gasses from one of Svartsengi’s thirteen boreholes leaked into his water supply, filling his apartment with hydrogen sulfide and carbon monoxide.

White: The color of the lava rocks beneath our feet. The color of the mud masks on our faces. The color of the tourists’ skin beneath the masks.

9 Vesturbaejarlaug

I pay 900 ISK to enter Vesturbaejarlaug, plus 300 ISK for a rental towel. It’s a pubic geothermal spa is in a northern neighborhood of Reykjavik, located between my small temporary apartment and a muddy beach that looks out to sea.

The scene would make a lackluster tourist ad. A young couple is turned toward each other in the shallow pool. He’s lying outstretched, the locker key fob on his ankle. She’s floating on her stomach, shoulder bones protruding under her wet hair. Two thin women hold their toddlers upright in the water, likely talking about the children’s habits, preferences, and progress. A stooped man of eighty closes his eyes gently, beside a crop of teenage boys. A woman with bottle-red hair crosses her arms over the rounded ledge. She’s looking at the big pool where a dozen other women in skirted one pieces bob up and down in synchrony, waving their arms. Drifting above is the opening trumpet line of “La Vie En Rose,” a track played on the aerobics instructor’s CD player.

The bathers lack the glamor of the blond woman swimming through the pages of Iceland Air’s in-flight magazine; face mask set, cocktail in hand. She is meant to represent me, were I to visit the Blue Lagoon. There, the electric blue water is pristine and surrounded by volcanic rock. Entry fee, 6100 ISK, plus 2300 ISK for the cocktail.

Here, the water is clear and the frigid pavement is coarse and familiar. I ease into the shallowest pool where the bathers rest their backs against the curved edge, toes floating inches from each other. I slide down until water rests at my neck. After a few moments of total immersion, muscles tenderize, and thoughts slow.

10 Videy Island

In Reykjavik, there is nothing left to do but board a small boat and motor across the harbor to uninhabited Videy (pronounced fithy) Island to walk and stand in the company of stone plinths imagined by Richard Serra and assembled in 1990. Serra is a frequent companion of mine in San Francisco where his work inhabits an indoor space, free to all visitors. I wander there in his curving iron facades and remember that art is all that matters. Here in Iceland, in his largest land art installation, en pleine air, the stone towers frame the entire sea and sky, blue and pale pink and all getting more vivid as the sun burns through cloud. Arctic terns besiege the bright green, flower-japped four-hundred-acre island, nesting and gaining strength for the world’s longest avian migration. They are indifferent to the Serra work, as birds tend to be about art in general, yet their presence and their sharp cry are immutably attached to experience of these stones on this island in this moment in time.

11 Springbreaking Sweet

For me NonFictioNOW was like a special celebration of the coming of spring. After a long dark winter in Iceland we celebrate spring and summer to the extreme. We even have a holiday called the First Day of Summer. Everything that cheers us up is a token of the arrival of spring. So it was inspiring to join in the busy crowd and feel the energy at the conference.

In April the First Day of Summer is celebrated outdoors with parades all over Iceland, usually in quite cold weather. It is also traditional to give summer gifts on that day. Nowadays the kids get small toys to use in outdoors play.

Several northern towns do not have any sunlight for a few months. In those places, it has become a tradition to celebrate on the day the sun is seen again, sometimes after as many as three months of absence. Reykjavík is not among them, but winter can be bleak here, especially if there is no snow like last winter.

And everybody waits for the Golden Plover. A little bird that flies half the globe to stay here for the summer. It is beautiful, the black chest embroidered with white as if it is wearing a Chanel jacket. All news media compete to be the first to convey news of its arrival. It is called the Springbreaking Sweet and there are many poems and songs about it.

12 Conference Impressions

Over the last few years, my impression has been that literary/creative nonfiction is becoming more diverse and inclusive, as well as more expansive. And that sense of things evolving and changing became even more evident at the recent NonfictionNow conference in Iceland. I say this because the range, scope and variety of the majority of panels and round tables is making me think that we are perhaps in the midst of a paradigm shift, what Phillip Lopate calls “the new nonfiction.”

By this I mean that at NonfictionNOW there was less emphasis on the more traditional forms of narrative nonfiction, and less on/about issues of craft than I’ve seen at past conferences. This year I attended several discussion/presentations on hybrid and interactive forms; sessions, for example, on/about mixed media, graphic and visual, lyric/poetic forms. Moreover, there were panels on/about gender and identity politics; political, social, and cultural matters (environment, climate change, place, marginal populations; world events, etc), in addition to sessions on/about identity politics, ethnography, scholarship, and research.

All of that said, this isn’t a rant, complaint, or a judgment. Given the significant changes in the larger culture, this is an inevitable shift—an indication, I believe, of how wide-ranging and experimental the genre has become. It’s much like what’s happening in the other contemporary fine arts–visual art, dance, theater, and music-both in composition as well as in performance.

NonfictionNOW then, was exactly what it’s title suggests. It’s a big tent, however; and there’s room for everyone–from traditional to experimental. It’ll be interesting to see how these changes will play out in our own writing and teaching of the form.

13 Ragnar Kjartansson’s An die Musik

My mind is fine-tuned to visual art at this particular stage of my writing and after three days of conferencing, a gallery is important: consolidation and reflection. I walk into the space and hear a dissonance of sound, but it’s a floating dissonance, so it’s something I know to be curious and conceptual, something seducing. There are five pianos, the tops of which are lined with fruit, wine, beer, chocolates, pastries, and there’s a pianist and opera singer at each piano who all perform the same song—Shubert’s “An die Musik,” but do so at different times so that they’re slightly off. They do this for seven hours straight with only a fifteen-minute break, and it’s a mess, actually, and I laugh and I laugh and I laugh. Eventually I’m crying. There’s great beauty in this chaos. While I’ve been in Iceland to further a conversation I want to have with others who also want to have it, my middle child is vomiting daily with abdominal migraines (the name! the name!) and I feel guilty and wrong that I’m enjoying myself, meeting new people over lobster bisque, taking photos of glaciers and soaking in hot springs when I’m not devouring Daudet’s In the Land of Pain. But from this distance I can see the beauty in the chaos of his illness that sucks me in daily, and I know that there’s no place I’d rather be than with him, unless it’s here, now, listening to this. I think about the chaos of the caring and of the loving and I smile and I smile and I smile, and still I cry.

14 Geysir

The Golden Circle lightened our window frames. All lava rock and waterfall, Iceland filled passenger side and driver’s side, windshield and rearview. My husband and I called our style of travel ready for discovery, but maybe we were unprepared. Always, we wanted the landscape to surprise us.

Truth is, there was hardly time to picture it. Moments before descending the deep green of Þingvellir, the crevice of Law Rock, the plunge of Gulfoss, I flipped open the travel guide and read a few paragraphs aloud. We looked at each other and opened the car doors for an experience.

I used to say I hated the moment an essay made the leap to Latin or Greek, didn’t believe the ancient had the power to reveal something new. It takes conscious work to perform an etymological search, to drag out an oversized edition of the OED or find a trustworthy website, work still to fold a word’s origin neatly into the expanse of an essay. It’s all mental stretch, all argument for metaphor’s sake. It’s all imagining the context of history—emperors, wars, suffering—but never inhabiting it.

That’s language for you. Failing.

Rarely do we stumble—in real time—upon the origin of a word.

But at the Golden Circle’s farthest reach, we did. Geysir anciently churns in that place, a thing named not for the phenomenon it represents, but the idea’s explosive source. Seeing that hot sulfurous pool is word made flesh, is time turned vaporous mist.

In the parking lot, I read that Geysir no longer erupts. Geologists have declared its dormancy.

And yet, I was moved by walking toward it, by standing close and still, imagining the power of the old thing.

15 Snæfellsjökull

The guide stopped every so often as we made our way up Snæfellsjökull, a stratovolcano with a glacier on top. During our third break, as we regarded our surroundings—snow and ice underfoot, sky too blue to be called blue, grey and black massifs in the distance, dark clouds threatening to erase the color overhead—he told me that extraterrestrials had been expected to arrive at Snæfellsjökull on November 5, 1991, to be exact. “There were many people here. And TV crews. A lot of Americans, I think.” I might have at least said something hollow in reply: “And I take it the aliens didn’t show?” or “They were all disappointed, I’m sure. The people, I mean.” Instead I smiled and dug my trekking pole in a little more deeply. I wanted to feel the snowpack’s stiff resistance. As I gazed at the Snæfellsnes peninsula, I wondered what it would be like to be out there alone.

The view sufficiently taken in and our group of nine reassembled, we resumed our trek to the summit we never quite reached. Three decided to hang back. A blizzard soon slowed the rest of us down. We put on harnesses, tied ourselves to each other, and trudged upward through boundless whiteness. After an hour of painstaking progress, the guide stopped, examined his devices, and yelled through the wind and snow: “We are close! We are close! There is a steep cliff somewhere here! I can’t see it.”

Earlier in the day, as I’d waited for the guide to pick me up in front of Reykjavik City Hall, a passerby had pleasantly said, “Hello.” And then, with a gravity that made me wish not to answer him: “Where are you from?”

16 Litill

I am deep inside a fissure in the Þingvellir National Park, rock walls on either side of me. I am between worlds here, the Eurasian tectonic plate on one side, the North American plate on the other. Halfway down the fissure is a placard which informs me that this is the site of historical executions- burnings at the stake at Brennugjá (Fire Gorge), beheadings, the drownings of suspected witches in Drekkingarhylur (the Drowning Pool). Above me is Gálgaklettur, “Gallows Rock”, where thieves’ bodies were strung up between two rocky peaks, their bones picked clean by birds before bleaching and hardening in the midnight sun. In ensuing centuries, their disarticulated skeletons scattered among the rocks as they were swallowed back into the fracture of the earth’s crust.

To be in Iceland is to feel my vulnerability splayed out irrefutably in the landscape before me. Everything here is infinitely greater than I: the weather, the incinerating heat rising from the earth’s core, the volcanoes jutting from the planet’s explosive outward force. The topography is a reminder of a vast timeline upon which my lifespan is wholly insignificant. Standing at the edge of Gullfoss waterfall, its enormous power causes my whole body to tremble with emotion, and a thought comes unbidden: If I were to take one simple step from my rock perch into this raging stampede of cold glacier water, it would engulf me instantaneously and snuff me out as effortlessly as the insects in its path.

I step back from the spray, a prehistoric instinct of self-preservation. In this tiny breath of time, I am still part of the landscape. I claim my stake, and hike back up the trail toward the car.

17 What Are You Doing Here?

We clamber over hills of gray gravel to stand on the cliff edge. Below us, the glacier lake is edged with ice that has frozen into giant white ripples so it looks like a fancy cake trim. Icebergs drift in the water— snowy white, blue tinged, some streaked with gray. Beyond the lake, the glacier is a bright shining sheet covering the volcano Öræfajöjull. Drips and crackles are what we hear, and the harsh kee-errr of an Artic tern.

It’s like being in a childhood story: magical yet terrifying; chillingly visceral. Time seems not to matter, and yet it does. This glacial tongue, Fjallsjökull, is part of the Vatnajökullglacier. Some claim that in two hundred years Icelandic glaciers will have completely disappeared; sea levels will rise, animal habitats will be lost. At the guest house where we stayed last night, the owner told us that Fjallsjökull has retreated more than a kilometer since the 1980s, and where once there was one large glacial tongue, now there are three smaller ones. Something needs to be done, but what?

We run down the hill to the edge of the lagoon, pick up bits of ice. The low sun shines and the top of the glacier gleams. Later, we scramble over large rocks to reach the giant misshapen ice-fingers at the glacier edge. Up close we can see flecks of brown clay caught in the ice. How long has the clay been trapped there? Thousands of years? More? Less?

On the way back, after trudging across the gray gravel plain, we cross a swing bridge and meet a nanny goat and her kid. They pass us by but after, the goat stops to look back. A quizzical gaze, as if to ask, what are you doing here?

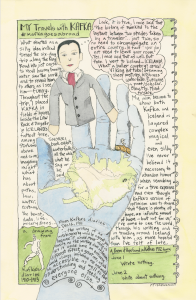

18 My Travels with Kafka

(See full size image in featured image above.) This essay appears in its designated spot in our print issue due out in October 2017.

19 Waterfalls/ water falls

This one shoots half way down the mountain before it flares on both sides, equally angled like the lacy skirt of a long skinny paper doll. These three appear in a row, thick and scraggly, the white beards of old men all needing a trim. That one folds over the edge like a table cloth. This one zigs and zags. That one forms water steps between the rocks. Many make me think of Rapunzel’s rippling hair cascading from her tower.

Over a snowy mountain pass, in the little fishing village of Seyðisfjörður with the requisite steeple-church and the boldly colored wooden houses, I count twenty-five. Down, down, down. Always descending. Dangling. Dripping. Dropping. Drizzling. Waterfalls. Water falls. Yet from a distance, they appear un-moving. Still. Washboards. Ropes. White chalk lines. The thinnest, nothing but strands of dental floss hanging from the cracks between Odin’s and Loki’s jagged rocky teeth.

20 In a Westfiords Hot Springs

Why do you think tourists come here?” asked Viktoria, who, seemingly out of nowhere, joined us in the isolated natural hot spring in Laugarholl, in the Westfjords. And we had thought the indiscernible steaming puddle of water, with moss-covered stones serving as tiles, was small for the three of us. How wrong we were.

“We don’t think we have anything to offer. We don’t have geysirs or anything here.”

It took us a good while to realize the tall, blond woman was serious, sitting there against the backdrop of dramatic mountains with the late evening sun coloring the wide-open, green space in front of them with a hue of yellow. After more than a decade abroad, she had returned to her nearby family farm and is raising five children. “I understand why the kids love it, but tourists?”

It wasn’t easy to convince Viktoria that we were genuinely smitten with the rugged Westfjords. With its hot springs. With its silence. With its cod and lamb diet. And with its frank people, who might jump in a pool with you and tell tales of a farm that had belonged to the family for almost a thousand years.

21 Fairytales and Myth

I did not expect to awaken my childhood passion for fairytales in Iceland, but the landscape teemed with the illusion of magic and myth. Wherever I looked while I traveled about, I expected to see sprites and trolls peeking out from beneath the roadside clumps of wild ladies’ mantel, or hiding under delicate leaves of maiden hair fern. I was sure I would eventually see a tiny fairy splashing about behind a waterfall pouring like a pitcher from the edges of nowhere, or catch a troll spying on me among the rocks in a lava fields wearing a coat of gray moss.

A fairy could easily be secreted away, I decided, in the lavender-colored lupine beside the banks of the countless icy blue streams I passed in my travels South, or tucked into the crags and cracks of lichen covered rocks along the way. And I found myself looking for them out the car window,

as mile upon mile of green, treeless, fields rolled by. Sometimes, I thought I saw tiny bits of their wings caught on the branches of the wooly willow bushes, leaving faint traces of gossamer and glimmer.

I easily imagined, while walking a trail, how spongy reindeer moss would make a luxurious bed for them—and so pretty, with a dotted coverlet of pink arctic wildflowers. Do they dine on the tiny wild strawberry berries, rhubarb, and basil that perfumed the air? Imagine the magical creatures of Icelandic lore sipping frothy glacier water stream side, from yellow buttercups. By trips end, it’s wasn’t hard for me to do.

22 Reykjavik Ink

It begins to rain cold and windblown as I walk the city so I wait out the weather in the Settlement Museum. Elevated above the ground as if upon a funeral pyre the shape of a Viking Longhouse has been reproduced with entryway, sleeping quarters, cook fire. Along the walls scraps of bone and driftwood where letters, maybe symbols have been scratched out. Notes of possession, the museum explains. In the children’s area, a pile of bones and a mystery for little ones to solve: at the threshold of a longhouse, buried among the wall’s stones the skeleton of a woman, three cats and the skull of a horse was discovered. Who, the display asks, do you think she was? Outside it is still raining so up the street I slip into the Reykjavik Tattoo Expo held in the ballroom of a hotel where crystal chandeliers snow dapples down the fancy wallpaper. A tattoo is something that outlives the spirit. Mostly the kids here are getting flash pieces inked, the easy choice. Smell of wet cigarettes, nervous sweat. I strip off my jacket and roll up my sleeves—the only time my arms are exposed in Iceland—and an artist from Austin, Texas, looks at my skin and its art and tries to get me to pay for a quick stamp of his needle. No. What would it mean? Languages die or live or survive like people, through love. Sometimes no one remembers them anymore but our human eyes recognize the scratch as something more than the fissures of time or the shaving of a glacier. Who was she? In my pocket, I finger a blank beach stone, my only souvenir. She was a question mark, shaped like a fishhook pulled down through dark water by the weight of a period.

23 At the Flea Market

In Reykjavik, I bought an antique thimble from a woman with a gray flat top and a long skinny braid down her back. “My mother was a seamstress,” I said.

“Where are you from?” She wore black jeans with a black T-shirt; her large breasts pushed against me. I told her the United States.

“Oh,” she said. Her body pushed in closer to me. It wasn’t sexual but there an urgency there to communicate, to share space and ideas.

“Yeah,” I said in answer to the question she hadn’t asked. “It embarrasses me to say I’m from the U.S. now. With him in charge.”

“What will happen?” Her eyes crinkled with concern.

“Hopefully he’ll do something so wrong, so quickly, that he’ll be fired.” My husband back in New York had stopped cutting his hair in protest and said he wouldn’t until Trump was out. His hair was a wild mess.

As I looked at a tiny doll holding a tiny cup, I told her I collected small things: fake food, children’s eyeglasses, antique paper clips, old thimbles. She nodded but looked distracted. I got the sense she wanted to talk politics, Trump, North Korea, maybe Brexit, but I wasn’t up to it. The midnight sun had hopped up my night owl tendencies tenfold. Each day kept giving and giving, and I kept taking. I hadn’t slept at all.

“My mother gave me a dollhouse when I was a child,” I said. “She sewed curtains for the windows and hung them with thumbtacks and dental floss.”

The woman must’ve seen me eyeing the antique thimbles, because she pulled one out and placed it in my hand. “This is old,” she said. “But useful.”

She threw in a skeleton key for free.

24 Endurance

Two days before I was to leave Iceland, with a hangover induced by potent Icelandic beer, I hurtled north in my rental car, aiming for the remote westfjords. I wanted to see something that would transport me, set fire to the heavy clothing of my anxious self. I was in such a hurry to see this something that I drove for twenty hours rather than sleep, knowing the light would follow me into the night. In early summer, the midnight sun seems to set and rise all at once, winking just near the horizon for nearly five hours straight. It was like a striptease, purpling and pinking the known world in a display that felt too grand for one—almost tragic in its excess. I drove until I could barely keep my eyes open, so exhausted I was nearly delirious. Then somewhere near a desolate pink beach under an ice-capped black mountain, but far from the nearest town, gas nearly on empty, I stopped to pee. Ass bared to the obscene sun, I recalled a conversation I’d had in a bar in Reykjavik. An artist and writer I’d just met said he was called to artists and writers whose work tested the limits of endurance, Ragnar Kjartansson, for instance, and Karl Ove Knausgaard. The act of endurance forces new ways of seeing, I had agreed. The mind is left with no other choice. For a moment, the sun seemed to fall away, like a star into space.

25 Oh, Darkness!

“It’s broad daylight outside and it is four o’clock in the morning. I haven’t gone to bed yet but am wide awake . . . I might as well write.”

—Harker’s 3rd Journal Entry, Makt Myrkanna (Powers of Darkness)

I barely slept during my week in Iceland, wind-throttled by day and disoriented by night. I found it thrilling. I let Iceland happen to me, in all its power and sulfur, starkness and majesty. Better to crave darkness, in the vampiric way, than try to keep hold of the diurnal routine.

I was smitten by Bríet Bjarnhéðinsdóttir, when I learned of her on a plaque in the old clothes-washing station in Laugardalur Park. Briet laid the ground for women’s rights in Iceland. She founded a journal, made speeches, built girls’schools and got elected to Reykjavik City Council. Also, I heard, she got the streets paved.

Briet’s husband, Valdimar Ásmundsson, scholar of sagas, translated Bram Stoker’s Dracula and serialized it in his newspaper Fjallkonan. In 1901, Icelanders read weekly installments, reviewing over laundry tubs the Englishman’s lust and cowardice. The “other” of Eastern Europe

and Dracula’s castle is also Iceland in Makt Myrkanna. It’s where light outruns darkness every spring and explodes as endless day, deranging the traveler. Where frank, determined women educate the unaware. Where ancestral castle is also the human heart, full of secret rooms and unexplored staircases, windows that open onto the wonder and horror of the world without.

Briet and Valdimar dreamed up Makt Myrkanna, lamps lit, children underfoot, in a new century and new Iceland theirs for the telling. It would fall to Briet to see the serial into publication as a book; Valdimar died in April, 1902, just as light began its annual reign over darkness, and Briet’s grief had nowhere deep to rest.

26

Possibly friendly but scary, near Lake Myvatn.

27 Laufásvegur Sunlight

The sun is out on this afternoon in Reykjavik, and as I walk past a house on Laufásvegur I see a woman standing up close to her front window, facing the street. Her eyes are shut and the sun illuminates her face. This spotlight of heat and light fixes her to her position, behind the schlumbergera plants on the sill and the decoration of ceramic angels hanging from the top of the window frame. The woman smiles into the sun, feeling its warmth on her closed eyelids. I soften my footsteps as I pass by, not wanting to come between her and the light.

When I tell Hilda, the young woman whose apartment I am sharing, about seeing the woman at her window she nods and tells me, quietly, “we have been waiting a long time”. After the long winter, the sun seems to fill your soul.

28 In the Midnight Afternoon

At 11:30 p.m. a police car streaks down Austurstræti. The spinning blue lights brighten our table at the Café Paris but my friend and I, talking hard, jazzed up by Reykjavik’s 24-hour daytime, do not look up until everyone else crowds the windows. What is it? Sirens are hourly in Chicago where I live. High-rise blaze? Heart Attack? Guns? Who knows. Chicagoans learn to partition attention but here one police car passes and everyone stops.

My friend and I go back thirty years. She lives in Boston now. We both believe in our clashing American cities, but are charmed by the space for friendship here, kept alert by the liminal vibe of all this light, talking deeper than we have for ages. A local told me he loves the cozy dark winters, but in summer he gets more done.

A tourist like me, with blond hair, tattoos, and a visibly queer disposition, has respite from my usual otherness here in this arty café city where the world’s first lesbian prime minister served almost a decade ago. Our local acquaintance told us women were not always welcome in politics, gays and lesbians were not always as visible as they are today, and trans people are still fighting. But Iceland, historically more often colonized than colonizer, seems less hostile than any place stateside. I can see the problems of my home in sharp relief from inside this hybrid night where no one expects the sirens.

The skirmish passing the Café Paris windows never comes to much. Our waiter says probably a drinking fight. Young Icelanders stroll hand-in-hand through the midnight afternoon, these bright nights their biggest bar season. But no, he says, police lights don’t pass by often here. We laugh, sharply. We are surprised to love this long tranquil daylight. When we get home we will think, when we hear sirens, in Iceland everyone would look up.

29 Keflavik Airport

Even though we are seasoned travelers, I try to listen to my twenty-five year old daughter answer the security guard’s questions before we board the plane. She looks at me and lifts her eyebrow, puzzled, but I can’t hear what they’re saying. Eventually, she boards the plane, and it’s my turn.

“Did you eat your grandma for lunch?” I wonder if it’s a trick question but he’s not smiling, so I answer, “No.”

“Did you or anyone else put the mouse in the freezer?” I shake my head negatively.

“Who is the last person that used your toothbrush?” This one makes me nervous since my daughter was always screaming that I was using her toothbrush. He finally lets me board the plane after I offer him my toothbrush.

I order a Bloody Mary, then one more before I start to read my graduate students’ creative writing papers. My daughter orders one drink after another and I give her that concerned look. “They’re free,” she says. She orders another and puts her headphones on to drown out me, the downer.

The first paper is twenty-seven pages and seems to be about a girl who dyes her hair often and has sex with endless classmates. I have an uncomfortable feeling this isn’t fiction, even though she classified it as such. I order one more Bloody Mary and turn on a movie.

30 Túnfisksalat

My suitcase is always heavier on the return. I’m drawn to how souvenirs turn the ephemeral into something tangible to hang on a wall. A scarf from a market or a glazed ceramic mug is an indicator of experience. “Objects are a way to orient yourself in the world” said the writers in the Object Lessons panel. But in the whirlwind 83 hours in Iceland, there was no time to browse vintage shops for knickknacks. My final purchase in Reykjavik was two Túnfisksalat sandwiches at the bus station. I ate the first sandwich standing by the open bus door two minutes before it pulled from the parking lot and brought us to the airport. “To write deeply about narrow subjects, you need to angle yourself into it, pick something small, use it as a returning point.” They said. What about writing narrowly about deep subjects? Can objects serve a similar purpose? A slice. A stand in. When trying to articulate the joyful entanglement of those four days Reykjavik, the timing of the trip during a personally dark, desperate winter, the perpetual daylight . . . I’m tempted to just focus on the Túnfisksalat. The cheap, prepackaged, white bread (soft, never soggy!) tuna fish salad sandwich available on all convenience store shelves. I couldn’t get enough of them. Maybe they were so good because they were always bought out of dire necessity: a quick bite between panels, a lining for the stomach before a night of dancing.

At home, in a bowl I picked up from a trip to Japan, I try to reproduce Túnfisksalat from online recipes. It’s not the same. The value of objects is largely weighted by time, by opportunity, the right thing at the right time.

Contributors

1.) Ann Leahy 2.) Dawn Raffel 3.) Leila Philip/Garth Evans 4.) Lisa Birnbaum 5.) Laurie Stone 6.) S. L. Wisenberg 7.) Elizabeth Kadetsky 8.) Ania Payne 9.) Lydia Wassan 10.) Leslie Roberts 11.) Asdis Ingólfsdóttir 12.) Michael Steinberg 13.) Heather Taylor Johnson 14.) Erica Trabold 15.) Suzanne Maria Menghraj 16.) Mieke Eerkens 17.) Catherine McKinnon 18.) Rebecca Fish Ewan 19.) Garnett Kilberg Cohen 20.) Piia Mustamäki 21.) Ryder Ziebarth 22.) Megan Baxter 23.) Anne Panning 24.) Kristen French 25.) Beth Cleary 26.) S. L. Wisenberg 27.) Vanessa Berry 28.) Barrie Jean Borich 29.) Diane Payne 30.) Verity Sayles