I Remember Joe Brainard’s Cock Pics

I remember the first time I saw Joe Brainard’s cock pics. His lover Kenward kept a box and I was Kenward’s curious assistant. The cock was lovely, the photos keepers, the sentiment a reminder things don’t change much. I’ve traded such with loves and lovers and strangers. We seek revelations, and seeing Joe’s cock was such a revelation, a more intimate look into his erotic art, or at least his erotic life, a look at his life with Kenward through printed black and white pics, snapshots kept in a box on a shelf not shared with strangers—though they’re likely public now, sent and stored with Kenward’s papers at the University of California, San Diego Library, so much for cocksure anonymity in any age, at any age, dead or alive, and no secrets kept in a world penned, painted, and photographed by New York School poets who kept and keep sharing each other’s art and private lives for others to look at and into through language and visuals.

I remember the first time I saw Joe Brainard’s cock pics. His lover Kenward kept a box and I was Kenward’s curious assistant. The cock was lovely, the photos keepers, the sentiment a reminder things don’t change much. I’ve traded such with loves and lovers and strangers. We seek revelations, and seeing Joe’s cock was such a revelation, a more intimate look into his erotic art, or at least his erotic life, a look at his life with Kenward through printed black and white pics, snapshots kept in a box on a shelf not shared with strangers—though they’re likely public now, sent and stored with Kenward’s papers at the University of California, San Diego Library, so much for cocksure anonymity in any age, at any age, dead or alive, and no secrets kept in a world penned, painted, and photographed by New York School poets who kept and keep sharing each other’s art and private lives for others to look at and into through language and visuals.

Not much is hidden of Joe—tan crisp, cock long and thick, balls heavy—in these pics, although he sports a skin-tight, tie-dyed tank top. It’s the cool kind of strange to realize these are all 1960s originals, down to the tie-dye, photographed in Kenward’s Vermont bedroom. Joe’s arms are crossed in front of and behind him. Kenward’s not the best photographer and crops off the top of Joe’s forehead, keeping his focus below the thick eyebrows, on his young god’s goods. Joe’s look is put-on bored and curious, a soft pout proud and pensive, strangely both pornographic and poetic. Kenward’s shots are amateur, without so much consideration as to clean up the background. In one picture there is laundry on the rocking chair. Another pic Joe’s sitting on the rocking chair, his underwear thrown on Kenward’s bedroom floor, next to the coiled rug, where never very much has been swept under.

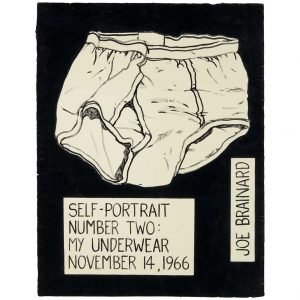

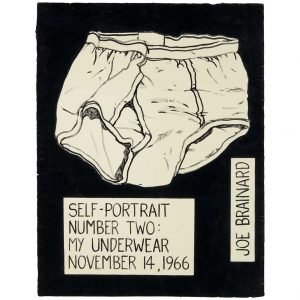

Of course I looked at Joe’s cock—it was Joe Brainard’s cock!—but I kept seeing the whitest thing in the black and white photograph. I kept looking at the briefs crumbled on the floor, knowing with the strange sensation that I’d seen the same white shape before, although myself no stranger to underwear quickly tossed disrobing for a lover or to send a potential lover a hasty unconsidered composition. I carried the picture along Kenward’s storied stairwell, among Joe’s art, looking for the image I knew I’d seen before, framed among Kenward’s collection walls.

I found it: Joe’s lightly penciled pair of crumbled paper briefs. I kept comparing the pic with the white collage, confirming a photo-to-art match. I admit to admiring Kenward’s collection of Joe’s cock pics, kept undisclosed for more than fifty years, stored now I suppose with so much boxed material sent to UCSD. It’s strange to consider what you can find when you know where to look.

Chip Livingston is the author of the novel Owls Don’t Have to Mean Death; a collection of essays and short stories, Naming Ceremony; and two poetry collections, Crow-Blue, Crow-Black and Museum of False Starts. His poems, essays, and stories have appeared in Ploughshares, Prairie Schooner, Mississippi Review, Cincinnati Review, Court Green, The Journal, and on the Academy of American Poets and the Poetry Academy websites. Chip teaches in the low-residency MFA program at the Institute of American Indian Arts. He lives in Montevideo, Uruguay.

Joe Brainard’s art work used by permission of the Estate of Joe Brainard and courtesy of Tibor de Nagy Gallery, New York.

“Hi, my name is Natalie King. I am interested in taking some acting classes.”

“Hi, my name is Natalie King. I am interested in taking some acting classes.”