A Look Back at a New Narrative

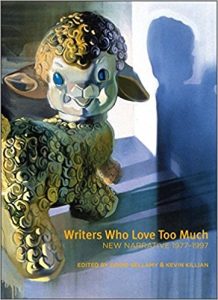

Writers Who Love Too Much: New Narrative 1977-1997

Nightboat, 511 pages, $24.95

Edited by Dodie Bellamy & Kevin Killian

New Narrative, a late twentieth-century art movement that fused queer praxis, radical politics, and daring writing, is now on arguably on its third or fourth “wave,” but I had not encountered it until recently. Now the similarly uninitiated can thank Nightboat for publishing the delightful and overdue anthology Writers Who Love Too Much: New Narrative 1977-1997. As editors Dodie Bellamy and Kevin Killian explain in their introduction, the movement reshaped narrative into “a system of writing designed to be optimally responsive to cultural and political change.” Indeed the personal essays, auto-fiction, interviews, and criticism in this collection explode notions of “good” writing and art in order to build something true to modern lived experience.

New Narrative, a late twentieth-century art movement that fused queer praxis, radical politics, and daring writing, is now on arguably on its third or fourth “wave,” but I had not encountered it until recently. Now the similarly uninitiated can thank Nightboat for publishing the delightful and overdue anthology Writers Who Love Too Much: New Narrative 1977-1997. As editors Dodie Bellamy and Kevin Killian explain in their introduction, the movement reshaped narrative into “a system of writing designed to be optimally responsive to cultural and political change.” Indeed the personal essays, auto-fiction, interviews, and criticism in this collection explode notions of “good” writing and art in order to build something true to modern lived experience.

Take Robert Glück’s “Sanchez and a Day,” in which a narrator and his dog must evade a truck of threatening homophones. Glück’s complex layering of memory and sensation sets up a left turn towards intimate (and overtly political) direct address: “I had angry dreams. Even in my erotic fantasies I couldn’t banish a violence that twisted the plot away from pleasure to confusion and fear. And what I resolved was this: that I would gear my writing to tell you about incidents like the one at Sanchez and Day, to put them to you as real questions that need answers, and that these questions, along with my understanding and my practice, would grow more energetic and precise.” The questions raised by Glück dictate the mode of writing, regardless of inherited notions of taste and “show, don’t tell.” As a reader, there’s some whiplash when the artful anecdote goes from consumable experience to a shared, solvable problem.

In Dodie Bellamy’s “Dear Gail,” the narrator describes her future lover’s eye contact as a “missile dying for a target.” That phrase could be used to describe many of the characters who knock around this collection. Indeed much of the writing, which first grew out of a free poetry workshop in San Francisco in the late seventies, uses desire as the lens through which the view the self, taking more narrative cues from pornos than from what’s traditionally considered literary canon. In Dennis Cooper’s “Square One,” a skin flick idol is held up as divine harbinger of grace and loss. “The actor’s beauty is God. Their sex is heaven . . . Never again will his face be as gripped by what’s deep inside him but slipping from his possession.” Eros and politics are forever intersecting, whether in excerpts by better-known figures like Eileen Myles’ (Chelsea Girls) and Chris Kraus (I Love Dick), or those by cult favorites like Lawrence Braithwaite. In the Braithwaite’s Wigger, language, desire, and racism push language to its breaking point: “He’d tug at the crotch of his slacks / rub his big belly—have his hand up by his chest (it looked like a thermal-photo) as Brian swayed, paced and gestured in his boxers / telling him about his plans to annihilate a body w/ the seduction of words and weapons / /”

Power dictates how stories get told, so it’s worth examining how narrative builds and reflects our understandings of the world. Writers Who Love Too Much offers an array of off ramps away from pre-made conclusions and towards more nontraditional (aka dangerous) modes of meaning-making. It can be hard to unlearn inherited notions of right and wrong. By making the “wrong” parts of personal experience (politics, kitsch, desire) so central to their work, the writers of New Narrative have complicated and broadened conceptions of what the modern nonfiction essay can do.

Timothy Parfitt is a Chicago-based essayist and translator. His writing has appeared in Deadspin, Thread, Newcity, Chicagoist, Timeout Chicago and Wassup.