Much like any great feat that we learn about in history class, the history of radio also involves tons of drama, competition, and lies. In honor of National Radio Day, let’s take a look at how radio has transformed from a singular letter being broadcasted across a pond to the communication waves transmitted right from our hands.

The first steps into developing the modern radio started out as merely a theory. Way back in 1820, Hans Christian Oersted, a Danish physicist, was the first to proclaim that a magnetic field can be created around a wire that has a current running through it. This was the first scientific connection ever found between electricity and magnetism (which is, like, really important.) This great proclamation was tested in 1830 by English physicist Michael Faraday and was able to confirm Oersted’s theory. He then established the principle of electromagnetic induction.

It wasn’t until 1865 that James Clerk Maxwell, an experimental physics professor at Cambridge University, published a theoretical paper stating that electromagnetic currents could be ‘perceived at a distance.’ Maxwell also threw up in the air the idea that these waves travelled at the speed of light.

In the late 1880s, German physicist Heinrich Hertz tested Maxwell’s theory. He succeeded in producing electromagnetic waves, and confirmed Maxwell’s prediction about their speed.

Marconi, 1890s

In comes Guglielmo Marconi, an Italian Inventor. Marconi was pretty much obsessed with Hertz’s success and realized that the waves produced could be used to send and receive telegraph messages. In 1896, Marconi’s first signals were able to be broadcasted but only about up to a mile away. He realized that this could be a huge deal and offered it up to the Italian government to continue his research. They denied (yikes) and he decided to move on over to England and take a patent out on his discoveries to further his experimentation.

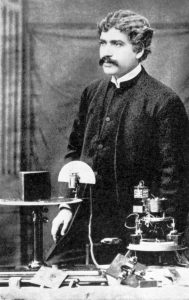

JC Bose, 1897

Around the same time, Indian scientist J.C. Bose demonstrated a radio transmission in Calcutta in front of the British Governor General. The transmission was over a distance of three miles from the Presidency College and Science College in Calcutta. Unfortunately, Bose is often overlooked when discussing the ‘discovery’ of electromagnetic waves and their uses. Bose literally solved the problem of the Hertz (signals) not being able to penetrate through walls, mountains, and water.

Here’s where the historical tea kicks in. Bose repeated his earlier demonstration at the Royal Society in London in 1899 in the presence of a bunch of very important scientists and noblemen. Our good pal Marconi was also present at this Royal Society meeting (this will be important to note…)

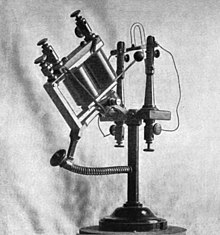

A coherer

In 1901, Marconi launched the Mercuri Coherer, a form of radio signal detector used in the first radio receivers that all of these guys were trying to perfect. Mr. J.C. Bose just so happened to lose his notebook at the Royal Society meeting. In that notebook Bose had included a drawing of the “Mercuri Coherer with a telephone detector.” Coincidentally, the coherer drawn in Bose’s notebook was the same exact one that Marconi had launched. Apparently, Marconi was unable to explain how he got the design. He said that an Italian Navy engineer, Solari (Marconi’s BFF), had developed it, but Solari later denied it. Marconi then said that Italian professor Tomasina gave it to him, which later was exposed as a lie by another Italian professor, Angelo Banti. Unfortunately, Marconi had already been receiving international recognition for this great feat, thus leaving Bose in the dust (in terms of celebrity.)

Stubblefield, with his later, induction, wireless telephone, 1908

Within the scientific community, it can be said that Nathan B. Stubblefield, a farmer from Kentucky, made a voice transmission four years before Marconi transmitted radio signals. The story goes, in 1892, Stubblefield handed his friend Rainey T. Wells a box and told him to “walk away some distance.” Wells said later: “I had hardly reached my post.. when I heard ‘HELLO RAINEY’ come booming out of the receiver.”

For years and years, Stubblefield denied up to half a million dollars worth of investments from scientists, investors, and clout chasers alike to help further advance his contraption. Some time later, he was swindled out of all of his stocks in an investment company and died alone in his shack in 1928. His cat had mutilated his eyes in search of water and all of his radio equipment was gone.

Although we may not know exactly who physically put together the first radio device, it is widely known that in 1893, Nikolai Tesla demonstrated a wireless radio in St. Louis, Missouri. Despite this demonstration, Marconi is the person most often credited as the father of the radio. Marconi was awarded the very first wireless telegraphy patent in England in the year 1896, landing his recognition in radio’s history. A year later, Tesla filed for patents for his basic radio in the United States. His patent request was granted in 1900. Regardless of who created the very first radio, on December 12, 1901, Marconi’s place in history was forever sealed when he became the first person to transmit signals across the Atlantic Ocean. (Broadcasting a single letter, ‘S’.)

The Brox Sisters, a popular singing trio, listening to the radio together in the mid 1920s

Now, let’s fast forward to the late 1920’s to the early 1950’s. This specific time period had every industry booming, crashing, as well as some amazing innovations. This period is also considered the Golden Age of Radio, in which variety shows, game shows, and popular music of the time drew in millions of listeners across America in search of entertainment. The radio is where people gathered together to get their daily dose of Louis Armstrong tunes and stock market updates. It was a very important piece of technology. With the introduction of television in the 1950s, the Golden Age began to fade. TV became ‘the thing’ and resulted in a difficult transition period. However, developments like stereophonic broadcasting, which began in the 1960s, helped radio maintain its popularity within society and kept it from bleeding out.

Some may say that radio is dead, but according to a 2019 study from Nielsen, 92% of the population (in America) still listen to radio every week. That’s approximately 272 million people! We also can’t forget to include the podcast craze that has been popularized by comedians, beauty gurus, and political science bros alike. It is very safe to say without the drama of racing to be the first to invent the radio, we wouldn’t have our beloved true crime podcasts. What else would we be listening to on our daily walks?