NOTE: Opinions and political views expressed by reviewing contributors are those of the contributor and do not necessarily represent the view of Punctuate.

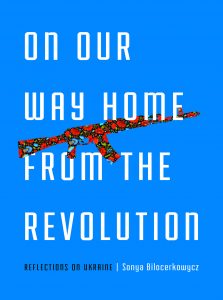

On Our Way Home from the Revolution: Reflections on Ukraine

Sonya Bilocerkowycz

21st Century Essays, $15.96

On January 8th, 2020, I awoke to the news that a Boeing 737 operated by Ukraine International Airlines and bound for Kiev had crashed shortly after takeoff from Tehran, killing all 176 on board. In the aftermath of the crash, aviation officials stated that their working theory was that the plane had been shot down by a surface-to-air missile, a theory which was corroborated three days later when Iran admitted that its military, on high alert in the wake of the US assassination of its top general, had indeed shot down the passenger plane because it mistook the craft for an American cruise missile being fired at an Iranian military target.

As these events were unfolding, I experienced an unsettling symmetry, having just finished reading the essay collection On Our Way Home from the Revolution: Reflections on Ukraine. I recalled the way in which Sonya Bilocerkowycz describes an eerily similar incident from 2014 in her eponymous essay:

MALAYSIA AIRLINES MH17 FLIGHT CRASH: 20 FAMILIES GONE IN ONE SHOT. While we were up on a mountain in Montana, kissing the cool air, an airplane was falling from the sky in Eastern Ukraine. Rebel fighters in the Donbass shot down Malaysia Airlines Flight 17 with a Russian-made Buk missile. The plane fell into a sunflower field.

Though the two events are separate conflicts and happened years apart, it struck me that they are both symptoms of imperial meddling: Russia in Ukraine and the US in the Middle East. For both countries the game has been on for decades and has been played using a full arsenal of creative strategies. In considering this, it also struck me that if even one American had been on the flight Iran shot down, our government would most likely have used it as a “shock doctrine” pretext for further escalation. We’ve seen it all before, many times over.

I think that is why another quote from Bilocerkowycz’s book has been ping-ponging back and forth in my head. It comes from the essay “Samizdat:” “History is on fast-forward, or maybe on replay.” Emblematic of one of her book’s major assertions, she uses this logic as an attempt to rationalize how Ukraine is struggling to free itself of occupation, a fight it’s been having for centuries against Russian forces or otherwise. Variations of this idea echo throughout her essays as the author situates herself as a Ukrainian-American seeking to disentangle the complicated histories of her family’s, and her country’s, struggle for survival and self-determination.

“I feel as if I am looking backward and forward at once, as if history is on a loop,” she writes in the essay “Swing State,” while regarding President Trump’s cozying up to Vladimir Putin; and later, in “The Village (Reprise),” while reading a pamphlet from 1950 meant to help Ukrainians fight the Bolsheviks: “as I read the first instruction (‘Explain to children that Russians are not our older brothers’), a hundred headlines from the current war shoot through my brain.” Her country’s long-standing suffering under Russia’s imperial zeal has created similar headlines, and similar traumas, across decades and generations of Ukrainians, like scars that still bleed.

This slippery relationship to time that Bilocerkowycz describes feels uncannily current, like an essential method of reckoning with the déjà-vu-inducing global events of the 21st century. There is a popular internet meme that comes from the television show True Detective (via Nietzsche, I should clarify, lest I invoke the wrath of any philosophers reading this) that is captioned with the quote “Time is a flat circle.” It is often deployed as a reaction to news that seems to indicate we are in the process of rehashing an idiotic strain of discourse, a deleterious cultural trend, or a particularly calamitous policy decision by one or another of our elected leaders. So, when the United States began the decade with an extrajudicial assassination of Qasem Soleimani, one of Iran’s most popular and influential figures, thereby dragging us closer to yet another war of aggression in the Middle East, I felt quite like Bilocerkowycz feels when regarding the Ukraine/Russia dynamic—that time is indeed a flat circle.

The structure of the essay collection as a whole keeps us keenly aware of this dynamic, circling back again and again to the pastoral setting of Bilocerkowycz’s ancestral Ukrainian village. The village, and its attendant history, is invoked in named interludes, but also breaks into other essays that otherwise take place in the present, creating through-lines that link events decades apart and cause the timeline to crease and warp. One of Bilocerkowycz’s central investigations is a recurring dive into the circumstances that forced her family to fight for survival as the land on which they lived was occupied by Poland, the Soviets, the Nazis, and eventually the Soviets again in the span of five years during World War II.

This is her family’s origin story, one that eventually leads to refuge in the Midwestern United States. We catch glimpses of the village through stories told by her grandmother from her Chicagoland kitchen as the smell of frying onions permeates the scene. We peer over her shoulder as she examines records from that tumultuous World War II era, trying to decipher what exactly happened when the Soviets had her great-grandfather, who was a leader in the village, disappear. And eventually, importantly, we see the village through her eyes as she visits her remaining relatives in search of some further connection to this place that seemingly will not retire quietly to the musty bookshelves of the past.

There is an admirable grappling here, as we see so often in books which invest time trying to describe a mixed heritage or immigrant mindset. Bilocerkowycz is not quite Ukrainian enough, having been born stateside, but still not quite American enough, evident in the way her childhood classmates would riddle her with questions about her unwieldy surname. This grappling is reminiscent in some ways of Aleksandar Hemon’s Book of My Lives, although it lacks the firsthand ties to “the old country” he gained growing up in Soviet Yugoslavia. This lack might have made Bilocerkowcyz’s collection seem disingenuous—like a way of inserting herself into a history she never truly experienced—were she not so upfront in her discomfort with this very fact.

In describing her time in Ukraine in 2013, during which she went to the Maidan protests that earned the country a new President, she writes: “I was a tourist. I left the revolution with a headache, and that’s all.” This discomfort persists—a nagging little notion that Ukraine is indifferent toward her, if not outright hostile. On one of her return trips to the village, her grandmother’s elderly cousin, Marina, forgets who she is and begins reprimanding her for being there: “Who are you? I don’t know who you are … Did you come here just to laugh at me? … I don’t know who you are, but you need to leave.” She does indeed leave, feeling guilty and rejected. But this does not stop her from continuing her search for answers.

While this discomfort is artfully portrayed, it is frankly expected that a collection whose subject feels split between two identities take pains to explore this difficulty. What I found myself truly enthralled by, what felt most urgent about On Our Way Home from the Revolution was Bilocerkowycz’s investment in dissent, in saying what is difficult, unpopular, or even downright dangerous to say. The essay “Samizdat” (a term referring to the dissident practice of copying and distributing literature banned by the Soviet state) is the collection’s best, weaving the author’s own experience being censured for an essay she wrote while teaching in authoritarian Belarus around the texts of other notable dissident journalists and novelists. Bilocerkowycz has an incredible talent for smuggling crystalline prose poems into her lucid analytical essaying—a bit like the act of distributing samizdat:

After classes, I gorge myself on experience: A bombing in the metro. The worst inflation rates in the world. Cookies with worms in them. Women tricked into ballerina bodies and sex tourism. Radiation fallout, blowing north with the wind, full of state secrets. Co-workers pointing to the ceiling when what they mean to say is our president. Jokes told over cognac.

Channeling the Romanian dissident author Herta Müller, she writes: “Grass grows inside your brain. It gets cut when you decide to speak.” After being suspended from (and subsequently reinstated to) her teaching job in Belarus for her essay critical of the dictatorship, she riffs on this line, writing that she is “an average sort of troublemaker, reckless with the lawnmower.”

This exploration of dissent segues into the essay “Swing State” which offers a scathing critique of the way many Americans—especially those in power—interpret ourselves and our partners in foreign relations. Characteristic of the collection, the essay builds a motif around a specific word: “thug,” using repetition with a difference to build an understanding bit by bit. Here the word is first uttered by an utterly sloshed Speaker of the House John Boehner, who Bilocerkowycz runs into while out to dinner with her mother and sisters in a nondescript Italian restaurant in South Dakota. When she volunteers that she’s moving to Ukraine in a few days, Boehner retorts: “Their president’s a thug … Putin’s a thug, too, he continues. All those guys are.”

This encounter forces Bilocerkowycz to consider what the word really means, and how readily it is applied to foreign entities, notably Vladimir Putin, by high-powered government slugs like Boehner. She draws quotes from Senators Mitch McConnell and Ted Cruz, both mentioning Putin as a KGB Thug, with the former adding: “I do think America is exceptional, America is different.” This begs the question: If being in the KGB makes someone a thug, how should we regard members of our CIA, with its laundry list of inciting coups and carrying out killings and abuses both foreign and domestic? And if Putin is such a thug, does that make our current president, who is so fond of him and his methods for quelling dissent, an aspiring thug? Bilocerkowycz quotes the journalist Anne Garrels, whose answer to the question seems conclusive: “The thing is, Vladimir Putin is a thug…But he’s their thug.”

Once again, this episode with John Boehner (now five years set out to pasture to drink all the Chianti he can handle) and his buddies tossing the word “thug” around to describe foreign leaders seems to grotesquely echo current events, perhaps because the present cannot be adequately distinguished from the past anymore. Consider how quickly American National Security officials, politicians (Democrats and Republicans alike, with the notable exception of Senator Bernie Sanders), and media rushed to label the freshly-assassinated General Soleimani a “terrorist” who was “threatening American lives and interests” in order to justify this sharp escalation toward further conflict with Iran. Consider that the second most powerful man in Iran was killed by a drone strike while on a diplomatic trip to Iraq, simply for defending his country’s interests against the power vacuum (created by American intervention and filled by ISIS) in his country’s backyard. If a man is a “terrorist” simply for overseeing the killing of enemy combatants by his troops, then how can our generals and their armies in the Middle East, having overseen an occupation of Iraq during which more than 200,000 civilians have been killed, be anything but terrorist forces? Consider that CIA “thugs” have been conspiring to meddle with Iran’s sovereignty since 1953, and how that still shapes relations between our country and Iran. Consider that Iran can’t attack American troops if there are no American troops blundering about the Middle East to attack. But now the political establishment, fresh off arming Trump with a new, bigger military budget, once again bays for war against the “terrorists.” “History is on a loop” once again as George W. Bush speechwriter David Frum, New York Times Iraq War propagandist Judith Miller, and a parade of other journalists, pundits, and Bush administration figures complicit in engineering the 2003 invasion appear on our tv screens to give us their enlightened takes on why Iran is an even bigger threat than Iraq was. We seem chronically unable to counter our own disastrous inertia, to see ourselves as anything but high-minded good guys, wronged when all we are trying to do is help. Bilocerkowycz writes: “As Americans, we like to accomplish things—make phone calls, write checks—and then move on with our day. We don’t have time to wallow over old ideology. We don’t have time to be reminded.” An image of President George W. Bush, standing at a podium aboard an aircraft carrier in 2003, making a speech in front of a giant star-spangled banner reading “MISSION ACCOMPLISHED” comes to mind. Is this future, or is it past?

On Our Way Home from the Revolution bids us to seek to understand the past, ultimately so that we forge a way out of the disorienting omni-present that defines our age. It bids us to have the courage to speak out against powerful interests that wish to keep us stuck in that deleterious loop. That being the case, we should count ourselves lucky that Bilocerkowycz’s book is not considered samizdat, that we can use that sliver of intellectual freedom to kick the door in, to hope for a tomorrow that seems increasingly less guaranteed. “I have heard that hope is a trap,” she writes, “but what if we choose it, knowingly? Is that not also our agency?” Not only is it our agency, but our responsibility as well.

________________

Jeffrey Barbieri is an essayist and an MFA candidate at Columbia College Chicago. He is originally from Rhode Island and carries that brusque New England cynicism with him wherever he goes. He can be found on Twitter.