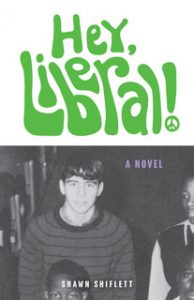

Shawn Shiflett is a Professor in the English—Creative Writing Department of Columbia College Chicago. He is the author of the novels Hidden Place and, most recently, Hey, Liberal! He was recuperating from a knee injury and slid gingerly into a chair in the Punctuate offices on a fall afternoon to talk about the sixties, his professional influences, and the lines between fiction and nonfiction.

Shawn Shiflett is a Professor in the English—Creative Writing Department of Columbia College Chicago. He is the author of the novels Hidden Place and, most recently, Hey, Liberal! He was recuperating from a knee injury and slid gingerly into a chair in the Punctuate offices on a fall afternoon to talk about the sixties, his professional influences, and the lines between fiction and nonfiction.

Punctuate: Simon Fleming, the main character of Hey, Liberal!, is a white thirteen-year-old attending a mostly black high school in Chicago shortly after the assassination of Martin Luther King. He’s placed there out of idealism by his socially motivated parents. Given the way the events of the novel unfold, are the readers to think Simon’s parents are naïve, delusional, or both?

Shiflett: That’s a question that comes up a lot. When does naïve enter into delusional? My parents have both apologized to me, though I don’t think they have anything to apologize about. I would not trade my experience of attending Waller High School for anything. You know, maybe it’s the whole country that’s delusional and not my parents. I mean, how are we supposed to rectify things if we aren’t even willing to get out of our segregated boxes? So in terms of parenting, sure, they were naïve, but in terms of American citizens, they were ahead of their time. I don’t have any anger towards them. I think it’s one-sided, and doesn’t see the complexity of how the legacy of genocide got us to where we are today to simply dismiss my parents as delusional. The paradox is that I wouldn’t put my son or daughter through a similar experience as the one I went through at Waller High. That’s the contradictory dichotomy within me now, and I don’t have a problem admitting it.

Punctuate: So you would answer neither?

Shiflett: I would say that my parents were naïve as far as parenting goes, but not naïve politically or in the grand scheme of things.

Punctuate: The novel is set almost fifty years ago, an era you experienced as a young person. What did you learn looking back on those days that you were unprepared for?

Shiflett: I learned how to be the other—what it feels like to be the other. What it feels like to walk into a room, and you don’t even understand what people are laughing about. At times, you’re not able to follow the conversations of those around you. An experience like that informs you in all things. And it’s not like I’m saying, “Oh, I know what it means to be black.” I can’t possible acculturate the entirety of the African American experience. That’s true. But you can learn what it’s like to be the other. So when you go into a classroom as a teacher, you know that if you have, say, one black student in your class, you better read some literature from his or her culture right from the get-go or they’re going to feel like their voice isn’t allowed inside that classroom. It doesn’t matter how kind you are to him or her. You have to bring their culture into the classroom in a meaningful way. So my past experience informs me in all kinds of ways when I’m dealing with students, and people in general. You have to take that extra step, reach out to people, be inclusive.

Punctuate: You have said that this book is inspired by actual events, but that you get bored with memoirs, so you deliberately set out to write fiction. Given that Punctuate is a nonfiction magazine, what did you find out about the intersection of reality and fiction in your own experience?

Shiflett: Great, now all my creative nonfiction author friends are going to hate me [Laugh].

Look, a well-written memoir is a fine piece of work, period. But for me, I think a story about a white boy getting roughed up for three-hundred-or-so pages would have been boring whether or not factually true, and also inaccurate as to the more complex and nuanced experience I went through. Once you start plotting a story and combining people you knew into a single character (that’s exactly what I did with Clyde Porter, Louis Collins and Officer Clark), there’s a lot more freedom to get at what I would call the “greater truth.” So that’s the route I chose in writing Hey, Liberal!. You can fluctuate tone, attitude, dramatic action, arrange your chapters so that characters intersect at critical times, conflict with each other, and then carry on with the story. Also, the novel form allowed me to go into many different points-of-view.

Punctuate: Though Simon’s cynicism and wariness are hard to penetrate, the characters of Louis, Clyde, and Mr. Lange serve as foils in various ways. What do you think Simon learns from them?

Shiflett: If he’s cynical, I’m not aware of it. I’m open to hearing that you’re seeing something I wasn’t aware of. He is definitely wary. He’s just trying to survive. He’s also young, only thirteen. Every other student in the book is older than him. Clyde, for example, is a lot more experienced than Simon; plus he’s in his cultural element at Dexter. Louis is seventeen. Me? I was actually only thirteen when I went to Waller High, just like Simon, so I was probably the youngest kid in the school. An added year or two makes a huge difference in anyone’s development at that age. All of this said, it’s interesting that I personally get accused of being cynical now and then, so maybe I’m just blind to that part of myself in Simon.

Punctuate: And maybe that’s a word I reached for faster than I should have. So let’s just say given his harden exterior in the face of his circumstances, how does he learn from these people in his life?

Shiflett: He’s been sent to Dexter High on a mission from his parents to get along. Some of the characters he meets are his  avenues to accomplishing this. Clyde, Simon’s only black friend, tries to help him, but at best their friendship has limitations and distance. Clyde can probably get away with coming to Simon’s house, if he’s careful. I had one or two black friends who came over to my house for lunch. There was a white gang in the neighborhood, so going to and from my house and school was problematic for any black friend. And there was no way I was going to safely be able to go to Cabrini Green, the public housing project where the majority of the black students at Waller lived. So Clyde and Simon had to have what I think of as an “outsiders” friendship. It’s a meeting of cultures with each boy curious about the other. Curiosity is great cultural glue. And Clyde has many different sides. He’s not at all a stereotypical kid. Louis, on the other hand, teaches Simon that he has a right to his anger and that each and every one of us is responsible for our own actions. That’s a lesson that crosses cultural lines, and so it should come as no surprise to anyone. Admittedly, Louis is a problematic character, but I don’t want to say too much more about him, as that would spoil the novel for readers. Then there’s John Lange, Simon’s communist biology teacher. Simon learns left wing politics from John, who is kind enough to take Simon under his wing. All of these characters contradict each other with Simon caught in the middle, struggling to come of age.

avenues to accomplishing this. Clyde, Simon’s only black friend, tries to help him, but at best their friendship has limitations and distance. Clyde can probably get away with coming to Simon’s house, if he’s careful. I had one or two black friends who came over to my house for lunch. There was a white gang in the neighborhood, so going to and from my house and school was problematic for any black friend. And there was no way I was going to safely be able to go to Cabrini Green, the public housing project where the majority of the black students at Waller lived. So Clyde and Simon had to have what I think of as an “outsiders” friendship. It’s a meeting of cultures with each boy curious about the other. Curiosity is great cultural glue. And Clyde has many different sides. He’s not at all a stereotypical kid. Louis, on the other hand, teaches Simon that he has a right to his anger and that each and every one of us is responsible for our own actions. That’s a lesson that crosses cultural lines, and so it should come as no surprise to anyone. Admittedly, Louis is a problematic character, but I don’t want to say too much more about him, as that would spoil the novel for readers. Then there’s John Lange, Simon’s communist biology teacher. Simon learns left wing politics from John, who is kind enough to take Simon under his wing. All of these characters contradict each other with Simon caught in the middle, struggling to come of age.

Punctuate: Your stepfather, John Schultz, who founded the Story Workshop at Columbia College, wrote No One Was Killed, which is an account of the events surrounding the Democratic convention in 1968. How were your views about this era you both wrote about alike and different? How did they evolve?

Shiflett: John was dealing with people on an adult level. I was dealing with people on a teenager level. Those are two very different realities. If you watch film clips of a race riot like the MLK riots, and you see rioters in the streets, they’re most often teenagers. That’s where the real violence is happening. Sure, there’s some older people looting stores, too, or getting beat by the police, etc., but mostly it’s teenagers. John dealt with political movements in the adult world. The inner city, young-adult world of the late 60s could be much more immediate and dangerous on a daily basis. Think of what I’m describing here as two overlapping world’s with two different sets of rules.

Punctuate: In the years since then, did you have any discussion about your involvement in—

Shiflett: Oh, yeah. John was my mentor as a writer for years. And he had such a good handle on so much of what was happening in the neighborhood from his adult prospective. Like with Clark, the cop in Hey, Liberal! who is permanently assigned to Dexter High. John would know that cops at high schools during that time period were always physically bigger, tougher—more “badass”—than your regular police officers. They had a particular title, too, though what that title was escapes me at the moment. So I would describe something or someone in Hey, Liberal!, and John would give me facts and background info from the adult world that I wasn’t aware of. He was a great resource like that. In particular, he knew how the Chicago Police Department worked inside and out during the late 60s—what the Red Squad was, how they operated, who’s phones did they tap, etc. Because my parents were political activists, they were definitely on the Red Squad’s radar. So John was constantly reminding me of what the big political picture was in Chicago at the time of Hey, Liberal!. And though he was very much a political progressive himself, he was also quick to point out the blind spots of white liberal logic. His mentoring gave me permission to trust and write my story.

Punctuate: So that brings me to my next question. One of the things I think is really interesting is, when you’re talking about John’s knowledge of Chicago, and certainly you’ve been here this whole time, so maybe you can address Chicago as a real-life character, as an evolving entity as you look at it and then remember that time. I mean obviously you’re dealing with back then. You know, Lincoln Park was a bad neighborhood—

Shiflett: It was a culturally mixed neighborhood. It’s just much more “yuppified” now or gentrified, if you prefer that word. There’s things lost that my book only touches on. I mean, there was a whole Puerto Rican community that was obliterated from Lincoln Park in the late 6o‘s and early 70’s. If you didn’t own your house, you were gone, priced out—poof! So my family was both trying to solve that problem and the vanguard of the problem at the same time. We moved into the neighborhood along with the artists that made Lincoln Park a cool place to be. Then before you know it, you’ve got all your lawyers, doctors, people in finance, and so many other professionals moving in. I lived in Lincoln Park during its transition from multi-cultural to predominately white and affluent.

Punctuate: Are you working on anything right now?

Shiflett: Often, when people hear what my book is about, they’ll tell me a story concerning race that happened to him or her right around the same time period that my novel takes place. The stories sometimes take on a confessional sensibility. The tellers always say something like, “It was wild back then!” So I was thinking about recording people’s oral stories about race and see what evolves from these stories.

Punctuate: Given what is happening in the streets of St. Louis even as we are speaking, what is your view about the evolution of race relations in the United States fifty years after the riots at Dexter High?

Shiflett: We definitely have a systemic and ongoing national problem when it comes to race. And it’s definitely a problem that targets the black community as well as other communities of color. Let’s include the LBGT community in that assessment, too. I say all of this while also wanting to support good and honest law enforcement officers. They are, or should be, the walking embodiment of our United States Constitution. With the current technology—everyone has a cell phone with a camera now—we’re seeing what’s happening up close and personal on social media. I think as awful as these incidents are, they’re verifying what the black community has been saying for years. That’s a wake up call for those who didn’t believe them or, as is often the case, only passively believed them. I’m optimistic that some good will come from all of this. That’s my hope, anyway.