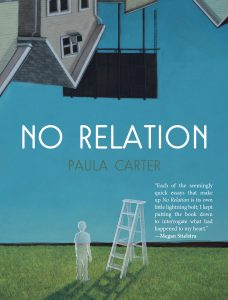

Paula Carter is the author of No Relation, a collection of flash essays that details her experiences helping to care for, and then leaving, two boys from her partner’s previous marriage. Incorporating prose poems, fairy tales, metaphors, and vignettes, Carter creates a mosaic of love and loss, longing and belonging, as she searches for the true meaning of family.

Paula Carter is the author of No Relation, a collection of flash essays that details her experiences helping to care for, and then leaving, two boys from her partner’s previous marriage. Incorporating prose poems, fairy tales, metaphors, and vignettes, Carter creates a mosaic of love and loss, longing and belonging, as she searches for the true meaning of family.

While No Relation is Carter’s first book, she also has essays published in The Southern Review, Kenyon Review, TriQuarterly, Prairie Schooner, and other journals. She is also a company member with 2nd Story, one of Chicago’s most prominent live lit events.

The interview with Carter was conducted over cups of coffee in her charming apartment in Chicago’s Andersonville neighborhood on an August afternoon.

SF: Nonfiction is a genre that is not so easily defined—especially when we consider the multiple subgenres that challenge its boundaries. Because No Relation is characterized as a collection of flash essays, I was wondering how you would define a “flash essay” in your own words?

PC: I think for me a flash essay is something that walks the line between prose and poetry in a way where the writer takes one significant moment—no matter how small it may be—and uses it to make larger connections to more universal themes. In this way, a certain theme is explored within a very short space and the subject matter becomes more immediate and crystallized for the reader.

SF: I really like that you used the term “crystallize” because it evokes the experience of how I read your emotions. In the book, you don’t overtly describe your emotions; instead, we catch these “glints” of an underlying emotional depth growing beneath the pressure of your prose. How did you write these crystallizing moments despite the extremely personal and emotional nature of the subject matter?

PC: When I began writing the book, I had written some standalone flash essays so I felt that I understood the tools of the form or, rather, the parts of the form. I had also read Safekeeping by Abigail Thomas which is written in these flash nonfiction moments and is also an amazing, beautiful piece of writing. I had all these feelings I wanted to express and when I read her book, I thought “This is the way I can do this,” because it allows me to share moments and construct scenes without a lot of explaining or exposition, which are great things in a regular essay, but, with this form, readers are asked to make certain connections themselves. I feel it leaves more space for reflection and interrogation. Also, without having too much exposition, I was also able to explore the power within my different relationships—with my ex-partner and with his two sons—in a more discrete way.

SF: What motivated you to take this dual experience of falling in and out of love with a romantic partner while also parenting his two children and turning it into a book of essays?

SF: What motivated you to take this dual experience of falling in and out of love with a romantic partner while also parenting his two children and turning it into a book of essays?

PC: The first impetus was that I had so many thoughts and feelings I wanted to express. I was so deeply affected by building my relationship with the boys and then having to leave them after my partner and I broke up. However, the second impetus was that I noticed there were not many books written from the perspective of a non-biological parent, or from someone who was in my position. When I was grieving the end of my relationship with my partner and his two sons, I was looking for books to help me cope and all I could really find were books in the self-help genre or books on how to create a successful blended family. I was frustrated that I couldn’t find many things written in a more creative genre or from the step-parent’s point of view, which led me to write my own essays about the experience.

SF: What is intriguing is that your essays are not solely focused on the narrative of developing and leaving these relationships; instead, your book also contains poetic language, definitions from the Oxford English Dictionary, a reimagined fairy tale and vignettes from your own childhood. Can you describe your writing process with No Relation?

PC: The very first flash essay in the book is the very first one I wrote. I wrote it just to quickly express how I was feeling in that moment, and from there, I decided to develop a longer manuscript. I created a list of memories of specific instances, places, or things that had stuck with me. I took each memory one at a time and wrote 500 words or so on each. Some of them felt complete—where I didn’t feel like I had to write more or cut—whereas others didn’t quite capture what I wanted, so I would keep trying. That was my process for a couple months.

However, as the list of memories came together, I started to recognize other themes I wanted to bring out and places that needed more depth. At one point, I had thought I might write a lot about the history of step-relationships or non-biological relationships with children, so I started down that path. This whole history did not make it into the final draft of the book, but there are a few essays that remained and they nod to the history of step-parenting stereotypes. The reimagined fairy tale was a way to acknowledge this broader historical and cultural context of step-parenting, but I also wanted to use the flash essay in a way to turn the dominant stereotype of the evil stepmother on its head.

SF: The narrative of your story is not only supplemented by these non-narrative essays such as the reimagined fairy tale, but also, follows a timeline that does not go in chronological order. Why did you decide to write a disjointed narrative?

PC: You know what’s interesting is that I made that list of memories and so I wasn’t thinking in terms of “What time am I writing in?” Instead, I felt more compelled to dive into a specific instance and explore it and then come back out and go into a different instance, regardless of where it landed in time.

SF: It makes sense now why memory features so prominently in your book and that you have several sections where you are “essaying” on memory—or, more specifically, how memory fails or how memory is vulnerable to change. You incorporate some neuroscience that asserts when we look back on memories, we are actually recreating the memory of remembering. With that said, how was it like using your list of memories and reconstructing them for the page?

PC: When it comes to nonfiction, particularly with memoir, I’m always aware of the fact that this is my narrative and it may not be someone else’s. I knew I needed to include some of those essays on memory—in part because I am writing about children and not my own children and that felt very complicated. I questioned whether I had a right to this narrative or if I was crossing a boundary by writing about their childhood. Additionally, when you write about a romantic relationship that ends, there are always two sides of that story: I might remember it one way and my ex-partner might remember it in another way. I wanted to make this explicit in the book.

In terms of remembering the memories themselves, they felt very vivid to me and I think it was because there was so much emotion and newness caught up in them. There was so much about my romantic relationship and helping to take care of the boys that was just so new to me and I think new experiences tend to imprint on you more clearly and concretely. But there is this constant question of what it means to remember and what will it mean for the boys when they get older—what will their memories be? That haunts me a little.

SF: You mentioned that raising the boys was so transformative for you. What transformed for you?

PC: So much, my goodness. When we’re younger, many of us have an idea of what our life will look like and that idea is presented to us in the media, or on television, or what’s historically presented to us: You get married, you have kids. So, for me, when I first met James and fell in love with him, I had to confront the fact that he already had kids. In a way, it forced me to rethink my idea of family and that was initially uncomfortable. I did not want to rethink my future and see that it would not follow the marriage-then-children narrative—that instead my family would include step-kids and an ex-wife. But as we all got closer together and I got to know the boys better, my resistance turned into acceptance to the point that it was to some extent harder to leave the boys than it was James after we broke up. The experience expanded my understanding of family and, also, my heart.

SF: One way you grappled with these complicated notions was through something that felt like “associative empathy,” where you would have one section focused on yourself and your own experience, but then the next section would revolve around a similar affective experience. For example, you bring in your cousin Elsie who was also in a blended family and you have an ongoing apostrophe to Octavia—Marc Antony’s second wife who raised his children from his first marriage and the children from his long affair with Cleopatra. Was this theme of associative empathy something that just happened or was it a conscious decision to link your story with others’ experiences?

PC: It was definitely a conscious decision, and it stemmed from not wanting to tell just my own story. Instead, I wanted to use my story to bring up larger and deeper questions on the number of people who are also in blended families, or used to be in blended families, and whose perspectives are not often addressed.

SF: Or their experiences are constrained in stereotypes?

PC: Yes, exactly. In terms of telling Elsie’s story, I wanted to bring in a different viewpoint of a blended family and bring out the fact that it’s happening in many different places and in many different ways. I think it also brings out the central question of the book: What happens when you’ve created a relationship with children who are not your own and then the relationship with their parent ends? How do you navigate their relationship? We really have no language in our culture to even identify what that relationship is—even when it is one that is surprisingly common, which I hope Elsie’s story helps to articulate.

For Octavia, however, I came across her story when I was researching the history of marriage and the history of step-parenting. I was so struck by how there is this common conception that blended families are a modern construct and how Octavia’s story shows that blended families existed from the earliest times. In fact, due to early deaths from diseases and complications with childbirth, step-siblings and half-siblings were common. Obviously, I have no idea how Octavia actually felt, but I kept feeling drawn to how similar our emotions might have been and I tried using my experience to put myself in her shoes. I could feel her so much that I wanted to give her a nod in the book.

SF: As your first book, what was it like writing No Relation?

PC: It was hard; besides my graduate thesis, it was the first time I had committed to a project this larger. It’s a short book, but it was, of course, so much different than thinking about something that is story-length or essay-length, which I’m more used to. It was a different place for me to go mentally, so I just committed to doing it. I thought, “This is my project and I am going to work at it and write this entire book and just see what happens.” I think a large part of finishing your first book is persistence, and saying over and over, “No matter what, I am going to do this.”

I also had first readers whose guidance and input I really valued as they read through different drafts.

SF: Do you have any advice for writers who are just starting out and need to locate first readers?

PC: I had three people as my first readers. I had two friends from graduate school and one friend whom I met in Chicago. All three of them were my peers; they were not my teachers or mentors. They were people who I felt were similarly on my level, who were committed to writing and engaged in their own work. I felt I could trust them because they understood what I was trying to do and where I was in my writing career. They were so generous in giving their time and input; and, of course, I am always willing to do the same for them.

My advice for people is to get involved in writing communities wherever you are—whether it’s classmates in school or in the town you live or if it’s an online community where people are sharing their work and working towards similar goals. Then, find the few relationships to people to whom you feel especially connected to them and whose input you value and start sharing work and encouraging each other. That is one of the things that has sustained me, encouraging and being encouraged by fellow writers.

SF: What are you working on now?

PC: I’m working on a couple things. The first project is a book, but I’m still in the thinking phases. I have three ancestors in my family who were the daughters of Iowa farmers at the turn of the century and they were pretty cool people. They went to college in physics and math, they never got married, and I’m really interested in their stories; however, I’m still in the research phase and I’m not sure if I will tell their stories straight through or fictionalize them.

The others are standalone essays that explore themes I’ve been thinking about as someone who has been mostly single throughout my thirties.

SF: Speaking of dating reminds me of the “Tupperware Test” in No Relation, where you decide if a date is worthy (or not) to take home food in the good Tupperware. I thought this section, and some other sections, were absolutely hilarious. How did you approach humor in this story, especially when we consider the serious subject matter?

PC: I wanted the book to have some levity in it. I often tell people what the book is about and I have to add, “But it’s funny, too!” Being able to see some hard experiences as also being a little bit funny works for me; laughing at myself as I tried to date after my relationship with James ended helped me a lot. I put a magnifying glass on bizarre situations and I can always find some absurdity and humor in them, too.

SF: If people read No Relation and love the flash essay form, what other books would you recommend to them?

PC: It’s becoming a more popular genre. I mentioned Safekeeping by Abigail Thomas—it is just a wonderful book. The online journal Brevity specializes in the flash essay and has a large and powerful selection of them. In Short, edited by Judish Kitchen and Mary Paumier Jones, was one of the first flash nonfiction collections. Department of Speculation by Jennifer Offill is flash fiction and it’s a really beautiful novel of short little moments. Finally, Citizen by Claudia Rankine is prose poetry—which is perhaps a close cousin to flash nonfiction – it’s an amazing book we should all read.