Reclaiming the Body

Touch has a memory. O say, love, say,

What can I do to kill it and be free?

—John Keats

Identifying Triggers

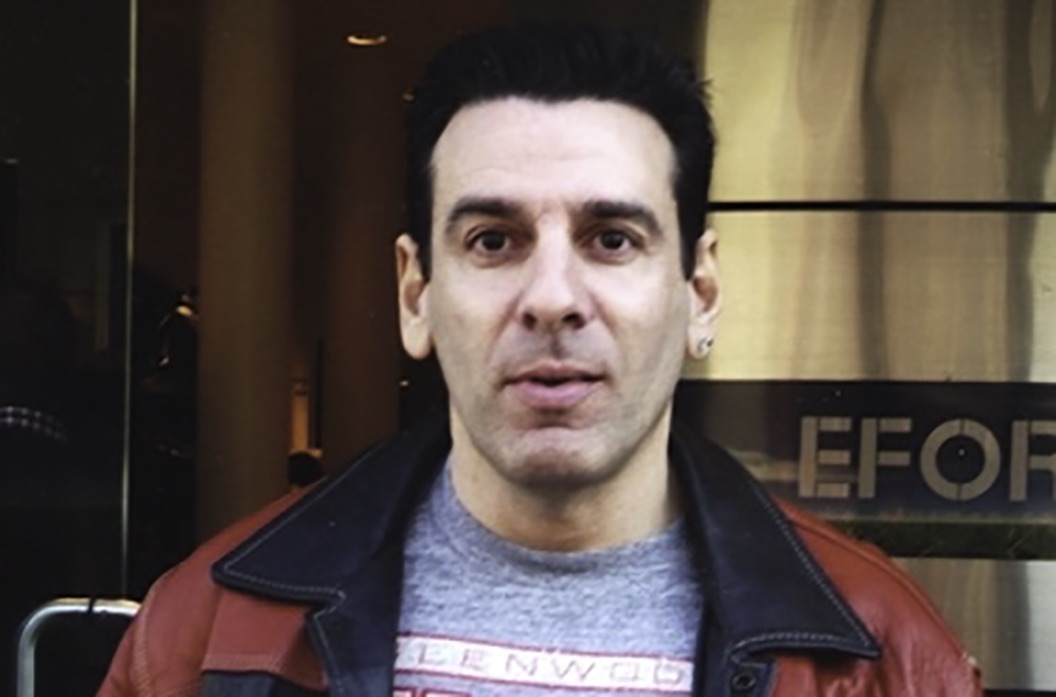

In a small gym in the hills of Pennsylvania, I stand barefoot on a filthy red mat with my arms folded, and watch sensei Nick, my crusty, tattooed, war-vet jujutsu instructor, demonstrate a sickle sweep on my tiny partner, Ruby, imagine a Scandinavian Audrey Hepburn with a metal rod in her back for scoliosis. A black belt in the art of aikido, Ruby can level a 200-pound man to the floor with a carefully timed pivot and a flick of the wrist.

Nick, who looks like he never left the service with his bulldog build, military fade, and the resting face of an Easter Island head, lounges on his back with Ruby standing over him. He explains, “You want to have a good prop on your partner, with one foot on her hip.”

As a nervous green belt, I never remember anything he says. Thankfully, both Nick and Ruby are very patient. Mid demonstration, Nick launches into a story, one foot poised to take Ruby’s leg out from under her. During the lull, one of my other classmates, a tall, solid, lumbersexual young man, Quinn, throws his arms around my shoulders from behind. “Show me what you’ve got.”

In a clumsy response, I drop to my knees and try to roll him. He makes a compliant groan, rolls over top of me, then jumps back to his feet and returns to working with his partner.

Quinn’s unexpected touch pulls a submerged memory from the bottom of my brain. I take a deep breath to keep my body in the room. But the trigger sets off a chain reaction of physical responses. A tactile memory from three years ago diffuses through my organs like a drop of ink into a glass of water. My brain seizes, heart pounds, stomach cramps, and I feel the fear of those about to drown, a rush in my ears, an arm around my neck, teeth sinking into my face, a hand pulling at my waistband.

I look at Nick, who is on his feet, and I give a slight shake of the head.

He says, “Hey Quinn, I need to talk to you for a second.”

I flee leave the room to run cold water on my wrists until my vision clears, until the visceral memory of the other man’s touch leaves my skin, until I am back in my body standing in an empty gym bathroom.

I return to the mat where Nick is waiting with punching pads on his hands. “She’s back. Proud of you.”

By the end of class, I want to tell Nick I’m going to quit. I’m deep in the bones exhausted from frequent nightmares. There are faster, easier ways to ground than mindfully practicing martial arts. Some people drink, snort, smoke, split open, turn on themselves or others. My habit is to turn inward. I sit on the mat while Ruby shows us our last move of the day and struggle against the fantasy of releasing endorphins by carving lines into my wrist with a box-cutter.

Cognitive Processing Therapy for PTSD

I went to my first jujutsuclass with gentle encouragement from my therapist. All my other ideas for coping and recovery were terrible. Our conversation went something like this.

“What if I have sex with a bunch of men?” I asked, fixing my eyes on the Banksy poster on my therapist’s wall. “I read an article where someone tried hook-ups as empowerment.”

My therapist folded her hands in her lap and raised an eyebrow. “Definitely not; it sounds exhausting. Part of recovery is managing these physical and emotional flashbacks and being able to live in the present. Have you tried any of the other grounding exercises? Using rubber bands or grabbing ice cubes? That shock can help your brain reset.”

I nodded. “Can’t I get a lobotomy?”

My therapist shook her head.

The memory of assault frequently hijacked my brain, so we had been reviewing it in small pieces by going through the Cognitive Processing Therapy for PTSD manualby Patricia A. Resick, Candice M. Monson, and Kathleen M. Chard. This process involved examining my beliefs about five often overlapping areas impacted by trauma: trust, safety, esteem, power, and intimacy, and how I have gotten “stuck” in unhealthy thoughts that keep me from healing.

She said, “You mentioned wanting to feel empowered. Would you be willing to try martial arts? A class might help you work through those aspects of your life impacted by trauma.”

I didn’t like making eye contact with waiters, doctors, sometimes my own students. Hugs from behind gave me flashbacks, close proximity with men, even gentle men, made me uncomfortable. How could I survive a martial arts class?

Trust: Patient examines trust beliefs related to the self and others and works on developing a balance of trust and mistrust.

When I googled jujutsu, some of my fears were confirmed. Unfortunately, there are psychological and physical risks to looking for exposure therapy on the mat. The sport requires mutual vulnerability and trust. Students need to be able to fall over and over again, navigate between legs and arms and groins, and be able to wrap arms around each other’s waists and necks. Some students take advantage of this close proximity. According to Jiu-Jitsu TimesandLadies Only BJJ, sexual harassment is common in some martial arts classes. Women and men have reported being physically and verbally harassed, from inappropriate jokes to “accidental” groping.

Averi Clements, writing for the Jiu-Jitsu Times, describes how when female students come forward with stories of harassment, they are often told: “Stop being so sensitive,” “you should feel flattered by the attention,” or “boys will be boys.” If a coach is unwilling to help, Clements’ advice is to leave the gym; when an instructor isn’t willing to put student safety first, get out. Some schools do take the extra proactive steps to make women feel safe and supported. Clements visited Pride Lands BJJ Academy in Monaca, Pennsylvania where the black belt teacher, Lou Armezzani, arranged the gym so that women were never changing in front of men, and men were not allowed to be shirtless in front of female students.

It’s the instructor’s job to make sure students feel like they are able to voice concerns, and instructors should be clear where they stand on sexual harassment; behavior that dehumanizes others will not be accepted on the mat. Clements adds a piece of advice to potential perverts, “If you’re one of the people who thinks it’s okay to treat your training partners like pieces of meat, kindly get the **** out of this sport.”

I stepped on the mat to reclaim my body, to make what Bessel A. van der Kolk, M.D. describes as the brain-body connection. Subjection to further harassment in what would become one of my safe spaces would be incredibly damaging —if my classmates betrayed the trust I put in them, I would plunge down another self-mutilation spiral. But I needn’t have worried.

On my first day of class, I told Nick, a two-tour combat medic in Afghanistan, that I had no prior experience with martial arts, only an intense fear of being touched. I knew anxiety was normal for a white-belt, but I warned Nick and Ruby that my brain responded unpredictably to touch. Nick understood.

“I don’t need details,” he said. “You’re in safe hands.”

Nick introduced me to my classmates and affectionately described his students as “the island of lost toys,” a hodgepodge of “rednecks, wrestlers, knuckle-draggers,” lumberjacks, good people with twisted senses of humor, broken and bent in all the right ways. I learned later that everyone in the room had a reason to be there: one student was recovering from child abuse, one had deep physical trauma from illness, and the instructor was teaching to protect us from his own past, one of war and degradation.

As I sat on the mat and stared at the thin silver scars on my wrist, Nick explained that he takes his role very seriously, plans for the worst-case scenario with every lesson, and makes sure that students have a useful self-defense move after the first practice that’s a balance of efficiency and economy of motion.

After the class warmup, Nick broke students into pairs. I worked with Ruby, who showed me a basic wrist lock. While Ruby enflamed the tendons on my arm by turning my wrist one direction and my elbow another, Nick explained that, “The goal is to expose you to a variety of techniques to bring out your natural abilities. Everything we teach should be adaptable to every shape and size that walks through the door, and the body type that you will become. I started as a kid and now here I am with busted hips and a shoulder with a three-year life expectancy.”

“A broken old man!” cried his protégée student, Quinn, from the far corner of the mat.

Nick gave him the side eye. “Experience is all you will have left because everything else goes to shit. Come here, Quinn. I want to show something.” Nick squared off with the young man and said, “We also want all the moves to be immediately practical. In a situation where confrontation is inevitable, get in, get out, and get home safe. Let’s say you leave here tonight and get jumped by some juggernaut.” He demonstrated a simple elbow lock on Quinn, getting the baseball grip on the wrist and putting his full weight on Quinn’s elbow for control. He took Quinn to the floor where the young man tapped out. Nick looked up at me. “I want you to leave here with something.”

After the first practice, the class claimed me.

I keep returning to the mat even though the process of mindful grounding is incredibly difficult, harder than graduate school, teaching freshman composition, or standing up in court to describe the man who attacked me. In the following months, Nick proved to be uniquely empathetic to my diagnosis of PTSD and sensitive to positions that I might find triggering. He never touched me without warning, and both he and Ruby developed an awareness of when I needed breaks from certain moves, sometimes even before I knew it myself (i.e. my glazed expression as a sign of internal collapse).

Safety: Patient examines beliefs about other people’s intentions to threaten or harm.

I didn’t start practicing martial arts because of Hollywood fight scenes, the prospect of winning competitions, or earning belts; I attended class because I wanted to sleep without nightmares, and I wanted to feel safer in my own skin. I was diagnosed with PTSD a few years ago after surviving, among other things, a sexual assault in southern India. I didn’t know I had changed until I came home and had a panic attack in my small hometown grocery store where I ran into a childhood friend’s mother. When she asked about India, I felt a wash of terror and a rush in my ears.

After that encounter, I started staying inside, cloistered. Avoidance of triggers that remind me of my trauma, feeling emotionally cauterized while simultaneously hyperalert, are common symptoms of PTSD. Because I was separately molested by a stranger and later by someone I trusted, I have deep fears that I will be attacked at any time by anyone, male or female, intimate friend or stranger; for a long time, these fears kept me from activities I once enjoyed, like travel and dancing in dive bars.

Many of my “stuck points” or unhealthy beliefs about my trauma, are related to my feelings of safety. My body often tells me I am unsafe, unsafe when a stranger sits next to me in a movie theater, unsafe with a student comes suddenly into my office to ask a question about grammar. I fear someone at an airport will bite me, someone will sneak into my house during the day and hide out in my attic to murder me at night, a catcaller escalating verbal harassment into sexual violence.

When I describe fears to my therapist, she always asks, “Those are all possible scenarios, but are they likely?”

We’ve discussed the likelihood of a man hiding in the attic all day; he would fall asleep on a pile of bat poop or get distracted by old memorabilia; we’ve imagined the likelihood of someone biting me in an airport, the place where everyone is suicidally exhausted.

Cognitive Processing Therapy for PTSD manual explains that because I grew up believing I was safe, the sudden disruption of this belief leads to social withdrawal, deep anxiety, persistent hyperarousal, and invasive fears of revictimization. Part of me believes the false statements that the world is dangerous everywhere and that all people will try to harm me, but jujutsuis teaching me how to resolve these beliefs, to accept that I can’t control future traumatic events, and to have confidence in my own abilities to manage my reactions.

I knew from attending therapy that there was no quick way to heal from trauma, but when I started attending jujutsuclasses, I was hopeful about the ability of martial arts training to lower the invasive impact of PTSD. Research backed up my optimism. University of Southern Florida researchers Alison Willing et. al. in 2019 conducted a study on veterans who trained at Tampa Jiu Jitsu. The researchers don’t claim jujutsucures, but they show that grappling on the mat is a way to manage symptoms; training might be a “complimentary treatment” to cognitive behavior therapy and medication. I look at practice as a supplement. Pills + therapy + jujutsuhelp me feel safer in my own body.

The recent study of Tampa Jiu Jitsu veteran-students echoes earlier studies published by University of Washington researchers David, Simpson, and Cotton, in their article for the Journal of Interpersonal Violence. They conducted a 36-hour “therapeutic self-defense curriculum” for 12 female veterans with PTSD. This crash course included elements of exposure and behavioral therapy. Six months later, the participants reported feeling less anxious and depressed. While the women’s hyperawareness and fear of re-traumatization didn’t change, the participants were better able to identify real threats.

From fall to winter, I made slow steady progress. I developed a higher tolerance for close encounters because I was forced to confront my avoidance coping mechanisms. When I first stepped on the mat with several loud, excited, young men, my gut reaction was to flee, but with repeated exposure therapy my brain adjusted to the guffawing, wrestling, intimate contact with people sweating enough to leave puddles on the floor.

A test to this feeling of safety came when Nick suggested that I start to work more with male students. No, I thought. Definitely not.

But during one class, Ruby was unable to get me to tap on an ankle lock, so Nick stepped in. “If I may?”

In a matter of a few seconds, his knee briefly slid near my groin as he adjusted into a scissor position. He took my leg and put it under his armpit while resting one foot on my hip to keep me from moving, his other foot under my thigh. With the blade of his forearm under my Achilles tendon, he rotated his body. But I was gone. I had the flash sensation of being on my back in a bed with broken springs. I didn’t tap out to signal him to stop the move until two pops exploded from my ankle. A spark of pain brought me back from that other place. I shouted “uncle” and started to laugh, delighted to be back in the room.

He pulled away from me and was on his feet, pacing. “What the fuck? Why didn’t you tap out?” He took a breath. “I need a cigarette.”

When he came back into the room, I was sitting on the floor in the corner watching the other students practice a stick drill.

Nick sat down next to me. “Hell. What a pair we make.”

“Trigger loop. You triggered me then I triggered you.”

“I felt your ankle give, and it gave me a flashback from the field.” He sighed and said quietly, “I hoped I wouldn’t trigger you, that you would feel safe with me.”

“Everyone triggers me. It’s not personal.”

“I know. It’s no more personal than what your ankle popping did to my brain. But I still hoped I’d be the exception. We’ll get through this together, though. You okay now?

Sharing this understanding of trauma with Nick, a man with fifty years of trauma, is comforting. Nick reminds me that PTSD has nothing to do with my size or gender.

I am triggered every class, but I never feel unsafe.

Esteem: Patient examines sense of worth. Being heard, valued, and taken seriously is basic to the development of self-esteem.

I learn in therapy that if individuals had positive beliefs about the self pre-trauma, they might struggle with shame and possible self-destructive behavior after a trauma. Sometimes my brain believes that I attracted trauma and that I deserve the resulting collateral damage to my sense of self. The good news is, jujutsuchallenges my sense of self every time I step on the mat.

When I finally execute a move I thought impossible to master, I’m slowly cultivating confidence in a body I often feel detached from.

My reasons for practicingjujutsuare similar to what inspired women during the Progressive Era. In the early 20thcentury, attacks against women increased as many shifted from the home to the workforce. Author and historian Wendy L. Rouse describes how immigrants and minorities were blamed for sexual violence as unfair scapegoats; women were and still are, often attacked by men they know. At the turn of the century, attacks were common in larger cities, but one woman, Wilma Berger, made the news for fighting back.

In 1909, 21-year-old Berger flipped a grown man over her shoulder and escaped from his choke-hold. Later, when the police doubted her story, she performed the move in the station for them. She believed all women should have the ability and the right to walk the streets unmolested, so she offered to teach others. Stories like Berger’s sparked the feminist origins of the self-defense movement.

As jujutsuclasses became more popular, first with the wealthy and then as an art that crossed class boundaries, critics grumbled. In her article, Rouse describes the many cultural and social objections to women studying martial arts: not only were women defying traditional gender stereotypes of the “weaker sex,” some critics said women “would become masculine through training” and that women’s bodies were not designed for aggression (although ju jitsu is Japanese for “the art of gentleness”). These objections were covers for the real concern that women’s physical independence might lead to demands for social and political freedoms. Despite these objections, women continued to practice self-defense for practical reasons. Many also felt a growing sense of confidence in their own physical power and right over their own bodies.

The process of rediscovering confidence in my body seems so slow that I am not always able to measure it. But during one class at the end of December, Nick told the class to line up. He presented me with a green belt and said, “I haven’t been this excited about a belt in a long time, probably more excited than you.”

I thought I didn’t care about leveling up, but the physical, vibrant representation of progress almost made me cry.

Power and Control: Patient examines beliefs of being able to meet challenges or control events.

My therapist explains that if I grew up believing that I had some control over events, the sudden shattering of that belief leads to internal emotional shutdown, repression, chronic passivity, depression, and self-destructive patterns. One false belief associated with this area is the idea that my trauma might not have happened if I had been in better control. Again, martial arts in an excellent way for me to learn that I don’t have total control, but I can have some control over my reaction to events.

Political and social dissonance in recent American politics regarding women’s bodies (#metoo movement and changing laws regarding abortion) has inspired more women than ever to practice martial arts as a way to feel what writer Catherine Lacey describes as the “empowerment principle.” She explains in one article for Voguethat women are on the mat not to lose weight but to find ways to cope with anxiety and depression. Lacey cites Sally Winston, Psy.D., a psychologist and codirector of the Anxiety and Stress Disorders Institute of Maryland, that martial arts offers women a chance to go “toward aggression rather than toward inhibition.” The mat is appealing, Lacey explains, because it’s a space for women to “enact a power they already possess.”

My trauma brain might try to convince me that I’m fragile, but the mat is a constructive place to act my persistent feelings of powerlessness. For example, when a man I hoped to never hear from again sent me a message on social media that triggered a chain reaction of rage and shame, I found peace in class. A year ago, I would have carved red lines into my wrist to stop flashbacks from hijacking my brain. But now stepping on the mat and throwing a few punches at broken-nose BOB (body opponent bag) helps. This freedom of sanctioned aggression in jujutsu, at least in my interior life, is liberating.

At the end of April, Ruby announced that she would be offering an aikido course in the fall. I didn’t know if the art would be a good fit for me. Her graceful fighting style requires a high level of precision that takes years to master. Nick said it might be “a little too flash and pop” for me. “You just want to punch people and throw them to the ground.”

I was able to attend a seminar with Ruby and other class members to watch her practice and to learn more about the peaceful philosophy behind aikido. It wasn’t until I attended that seminar that I developed a clearer idea of what I needed out of martial arts.

During the seminar, I sat on a bench in the host dojo to watch Ruby and another classmate train with the other seminar attendees. A framed quote by Morihei Ueshiba, author of aikido, hung on the wall of the dojo: “To injure an opponent is to injure yourself. To control aggression without inflicting injury is aikido.” The guest sensei for the seminar lit incense on the kamiza and lead the class in a quick mediation to connect with earth and air. The class warmed up; then she showed them a few moves with weapons. Partners bowed to their weapons each time the “blades” were passed back and forth. If the sensei paused from her rounds in the room to offer individual instruction, the rest of the class stopped what they were doing and dropped to their knees out of respect. This was a sharp contrast to Nick’s “dog pound school for miscreants,” as he affectionately called it.

When the seminar attendees took a morning break, I asked some of them why they chose aikido. One woman explained how karate kept her from responding to conflict by degrees. “It’s all punching, but aikido gives me a choice of how to respond. I don’t need to use the same level of force with everyone.”

Like jujutsu, aikido uses a “blending” technique between partners but doesn’t involve strikes. The art is almost like dancing and requires trusting your partner to lead and direct you across the mat. This ability to anticipate and react to a partner’s movement is called ukemi in Japanese. Good ukemi means the ability to receive directions, from being wind-milled across the floor by your partner’s arm or the ability to arc backwards into a fall.

Blending with an aggressor, turning physically and emotionally to see his or her point of view with self-restraint, almost sounds like empathy. This takes a leap of the imagination I’m not able to make yet. I do not want to blend. At least not today. While I look forward to the point in my healing process when I’ll be able to study the art, I currently lack the discipline, balance, nuanced and impeccable timing, and the head space. Aikido is for the long haul, a lifestyle, an elegant and occasionally theoretical approach to self-defense, but I need something today to help me with my nightly flashbacks.

Intimacy: Patient examines beliefs related to emotional needs, works on the ability to monitor strong emotions without self-harming and develops emotional connections with new people.

In discussions with my therapist, I learned that this area goes deeper than just romantic or sexual relationships and relates to my fears of never being able to connect with anyone again. Stuck points related to intimacy also include fears of being alone and an inability to self-monitor emotions. This lack of internal control inspires me to look for outside comfort, like the “maladaptive coping mechanism” of self-harming.

My ability to “self-soothe” was often put to the test after difficult practices on the mat. Even after six months of training, the class was a constant balance of fight, flight, or collapse. When class started doing over-the-shoulder throws and choke-holds, my brain sent me back to the street in India. I left class with an incubus on my shoulder.

When I got home the night of Quinn’s surprise hug, I sat on the edge of my bed and debated the merits of cutting. Nick knew the practice had been difficult and sent me a message. “You’ve found a way to be courageous without turning into something frightening. It’s one of the bravest things I’ve ever seen.”

No blades or blood. I took a deep breath and went to sleep.

But later in the week, I cut line after line and watched red beads form.

Discouraged, I asked my therapist for advice. I told her that I hadn’t had such vivid nightmares since I got back from India.

I described the recurring nightmare as if observing the action from the back of an auditorium. “I am walking home at night. The man on the red Royal Enfield drives past. Around the corner…” I stopped, feeling sick but able to breath my brain back from that dark street and ground in the corner of my therapist’s office, which was bathed in warm light and smelled like vanilla spice.

“How often are you having this nightmare?” she asked.

“Every night for the last couple of weeks.”

“Sometimes our bodies hold memories we think we’ve healed from. You’re putting yourself in triggering positions, so it makes sense that your body might work through those memories when you’re sleeping.”

My therapist sent me home with notes on treating nightmares with imagery scripting. In other words, nightmares are learned behavior, which means we can unlearn them, create new dreams during the day, and rehearse them. I imagined other people waiting for me around that street corner, Ruby in a unicorn onesie or my two-year-old niece extending a half-eaten cheese stick. Eventually, the dreams shifted tone. Instead of sexual violence, I dreamed about being able to escape trauma.

My therapist also recommended The Body Keeps the Score by Bessel A. van der Kolk, M. D. The author takes a comprehensive look at the impact of trauma on the body and brain. I particularly related to the sections that focused on survivor disconnection with their own bodies after trauma. Survivors often become fixated on either “dulling” or “seeking” sensations, like cutting, to distract themselves from their pasts.

My therapist asked me to consider which moves were the most triggering for me, and instead of dashing off the mat or quitting class, to wait through the panic. “Maybe next time you’re in class, test your limits and see what you can stand.”

van der Kolk explains contemporary neuroscience has shed light on how “our sense of ourselves is anchored in a vital connection with our bodies.” If survivors are unable to filter physical sensations because we’re trapped in the fugue state of trauma, the “price you pay is that you lose awareness of what is going on inside your body, and, with that, the sense of being fully, sensually alive.”

I still wanted to quit class. Instead, the next time I was on the mat with Ruby’s arm wrapped around my neck, I waited for panic to permeate my body; my feet felt the ridges of the practice mat under me, I smelled the perfume she put on earlier that day for her job at a school. On the other side of the classroom, Nick folded his glasses and set them on the table by the door. “Come here Quinn. Let’s throw a wrench into the curriculum.” Nick’s prodigy squared off with him, and Nick had the young man face down on the mat with one sweep of the leg.

“You going to let Nick take you out like that?” asked one of the other older students.

From his horizontal position on the mat, Quinn said, “Nick has his moments. He doesn’t have many left, so I give it to him once and awhile.” He groaned as he sat up. “Who am I kidding? He’ll fucking haunt me from the afterlife one day.”

“You okay?” asked Ruby into my ear. “Do you remember what to do?”

I took a deep breath. The panic of being pulled underwater, running out of air, not being able to touch the ground, passed.

____________________

Karen Bell’s work is forthcoming in Catamaran and Verity La and is the recipient of Crab Orchard Review’s John Guyon Literary Nonfiction Prize.