Paint Songs

There I am: a child, a century after the final painting in Monet’s bridge series is finished, coloring butterfly masks with my mom and my brother on the cement front porch of my childhood home. My mother had printed and cut out stencils for us to scribble on in the June mountain afternoon, and we were huddled between plastic totes of crayons and faded markers. I don’t remember what mine or my brother’s mask looked like, only that my mother’s was clean and purple and well-blended, and that I thought it was the most beautiful thing I had ever seen.

There I am: a child, a century after the final painting in Monet’s bridge series is finished, coloring butterfly masks with my mom and my brother on the cement front porch of my childhood home. My mother had printed and cut out stencils for us to scribble on in the June mountain afternoon, and we were huddled between plastic totes of crayons and faded markers. I don’t remember what mine or my brother’s mask looked like, only that my mother’s was clean and purple and well-blended, and that I thought it was the most beautiful thing I had ever seen.

I never used a lot of paint when I was little. Don’t misunderstand me: I painted all the time. But some pressing minimalism or frugality—really, when I think about it: a fear of using too much— kept my art sparing and seemingly sun-faded. My strokes were light, my colors always cool. I came to prefer watercolors because of how unobtrusive they were. The pastels and gradients soothed me. I understood that I could layer what I was trying to tell someone, but I couldn’t fix spilled paint. I was coloring lightly while my brother and friends broke crayons and pencil nibs to cover fridge doors with fearless saturation. I was holding my breath. I only realized this much later. You have to remember—the impressionists tell you to look at things from a distance.

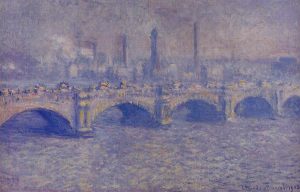

Monet’s bridge series includes four paintings painted between 1900 to 1903. Because of the fog that London wears like a dress, Monet was forced to consider the skyline and bridges as ghosts and implications. The Houses of Parliament and the traffic driving over the river are mere smudges of color through the vapor and sick breath of the Industrial Revolution. The paintings are like looking at city lights when you’re crying. Of the four paintings in the series, two of them are of Waterloo bridge as seen from Monet’s room in the Savoy hotel. One is painted in gray weather and makes the edges of my tongue prickle with its floods of contrast and dark green. The other is a wash of lavenders and pinks. The bridge in the second painting, finished three years after the first, is a strip of golden light. The art critics and historians talk about reversing techniques and color play, but all I can focus on is that bridge. It is the only thing truly legible in the painting, and I’m overcome with the urge as I’m standing in Chicago’s Art Institute, pretending to know what it means to be an artist, to climb inside of it and follow where that light is going.

You see, when I look at paintings, I want to touch them. I want to wrap them around me, paint side down, like a blanket. I want the colors to melt on my tongue like cotton candy and spiced dark chocolate. I want to plunge my hands in the paint palettes they were born from and smear their colors down my jaw and across my shoulder blades. I want my fingertips to fill the hollows in the strokes of paint. The vertebrae in my spine coil at the thought of color-laden brushes bending and trailing their weight across goose bumped canvases. Sometimes I drag my pen along my skin just to feel the ink.

In the art museums, the aesthetic reservations I had in my childhood are lost in the surge of tactility. The security guards keep watch at the corners of the rooms, and it takes all of my self-control to stay the three feet away for courtesy. It would be so easy to press one finger print against the varnish, to suspend myself between centuries and layers of turpentine, and find the artist crouching there. Monet would paint a bridge to tell me where to go. Degas would set tulle and spinning tops going in my stomach. Van Gogh would offer me yellow paint to put in my mouth, and I would accept.

Ayla Maisey is a nonfiction writer and photographer from Portland, Oregon, currently based in Chicago, Illinois. Her nonfiction and poetry have been published in Kenyon Review, Habitat, Glass: A Journal of Poetry, Brainchild, and the Lab Review.