Truth, Tyranny, and Avenues of Escape

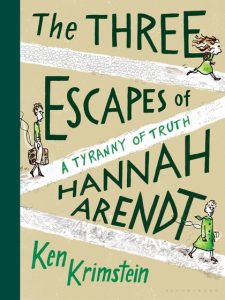

The Three Escapes of Hannah Arendt: A Tyranny of Truth

Ken Krimstein

Bloomsbury Publishing

September 25, 2018

240 pages, paperback

Those wishing to know more about the pivotal twentieth-century philosopher Hannah Arendt but who may be a little intimidated by her famous tomes (which sport such approachable titles like The Banality of Evil and The Origins of Totalitarianism) should check out The Three Escapes of Hannah Arendt: A Tyranny of Truth by Ken Krimstein. Krimstein, a cartoonist whose work has appeared in the New Yorker and the Wall Street Journal, has delivered a captivating graphic biography of Arendt’s life, one that puts key thrilling episodes of Arendt’s life in broader historical context, one in which her ideas and passions are convincingly rendered and readers get to see her political theories grow out of both love and in reaction to unspeakable horrors.

Those wishing to know more about the pivotal twentieth-century philosopher Hannah Arendt but who may be a little intimidated by her famous tomes (which sport such approachable titles like The Banality of Evil and The Origins of Totalitarianism) should check out The Three Escapes of Hannah Arendt: A Tyranny of Truth by Ken Krimstein. Krimstein, a cartoonist whose work has appeared in the New Yorker and the Wall Street Journal, has delivered a captivating graphic biography of Arendt’s life, one that puts key thrilling episodes of Arendt’s life in broader historical context, one in which her ideas and passions are convincingly rendered and readers get to see her political theories grow out of both love and in reaction to unspeakable horrors.

Her fierce intellectualism got her into hot water in her hometown, but was more welcome at university, where she enrolled in classes taught by Martin Heidegger, titan of twentieth- century philosophy and future Nazi sympathizer. Heidegger and Arendt became romantically entangled in what is one of the many aspects of Arendt’s life that resist tidy interpretation. Krimstein wonderfully animates scenes of public intellectual discourse, like at the Café Romanisches, where theorists, painters and composers drank, rubbed elbows, argued, and dreamt up artistic movements. Asterisks in the margins assist the curious reader absorb the importance of those present. Arendt’s most literal escape occurs when she flees Berlin and the closing vice of the Nazi’s final solution. Under the cover of night, under fake aliases, and using forged documents, she makes it first to France, then Spain, and then eventually New York City. We witness as friends perish, including her good friend, the essayist Walter Benjamin, who commits suicide on the Spanish border, unaware his visa would be approved the very next day.

After the war Arendt’s antifascist, anticommunist philosophy make her a postwar darling in the United States. Success does not dull her mind, though, and despite becoming a best-selling author and the first female professor at Princeton, she grew more and more disillusioned with the male-dominated discourse and the quintessentially male need to explain instead of understand. A surprise third-act reunion with Heidegger manages to be thrilling and sad, sentimental and politically consequential. Her clear-eyed coverage of the Eichmann trial in The Banality of Evil, coming so soon after the Holocaust, led some in the Jewish community to label her a traitor. Early in the book, Krimstein illustrates how Arendt would face similar criticism her whole life. In a single large panel, a childhood Arendt is surrounded by all the ways in which she was both “too much” and “not enough.” Too feminine, not feminine enough. Too Jewish, not Jewish enough. Arendt never was bashful, though, and one of the great joys of Three Escapes is watching her continually and delightfully blaze her own path. Writing and thinking are two activities especially hard to dramatize, but Krimstein’s evocative illustrations conjure Arendt’s mind and ever-present cigarette, and bring to life the communities of artists and thinkers from which Arendt, survivor, thinker, emerged.

Timothy Parfitt is a Chicago-based essayist and translator. His writing has appeared in Deadspin, Thread, Newcity, Chicagoist, Timeout Chicago, and Wassup.