So You’ve Got a Screenplay

You’ve done it! You’ve written a screenplay, developed the story, the characters, the everything so that your script reads as a tight, efficient piece of storytelling. You’ve even raised money that allows you to make the project, as well as found a cinematographer, production designer, and all manner of different crew members to help bring the vision of your script to life. But you’re not ready to shoot a movie yet.

One of the most important aspects of directing your films at Columbia College Chicago is all the pre-production that goes into it. And boy is there a lot of important pre-production. While this time frame of filmmaking is dominated by producers, who do all the magnificent work that allows a movie to go into production, you as a director must do your own work in order to be as prepared as possible on the days that you’re shooting. You can’t just show up to set and expect a movie to get made. You need to know what shots you’re going to get, how those shots will be accomplished and in what order, what shots you need in order to tell the full story, and how the framing and progression of those shots help you tell the story in the most appropriate way. And it all starts with lining the script.

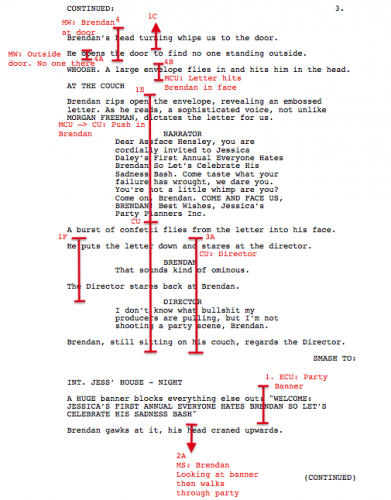

Yes. Literally drawing lines on the script.

Lining the script is drawing vertical lines on the script to delineate where shots begin and end, showing how much of the scene they cover. I like to generally structure it so that the wide shots are on the left and turn into close-ups as we move right across the page. This does a couple things for you: First, it lets you see if you are getting enough coverage of the scene. If you only have one line for half of a page, you might want to think about adding a shot to cut away to in editing (few things are more disheartening than finding out a shot doesn’t work after you’ve shot it and having nothing else to cut to). What this also does is show you if your shots evolve over the course of the scene. If you just have a ton of lines on the left side of the page, your movie has too many wide shots and not enough close-ups. The audience needs the shots to progress in some way (e.g. Start wide and push into closer and closer shots as the scene progresses) or the movie will be stale and boring.

After you line the script, you’re ready to start either storyboarding or doing overheads. I like to do overheads first.

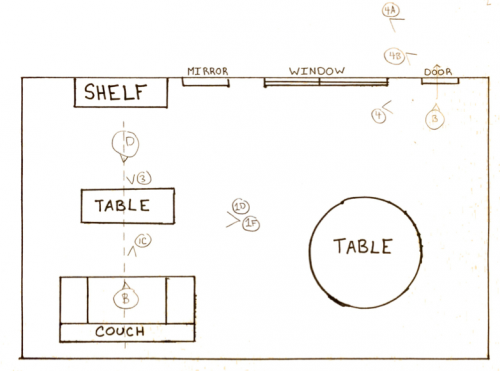

An overhead view of the room. I think they think directors are easily confused and need simple names for things.

Overheads use open triangles (the open side is where the lens is pointing, so it’s like a reverse arrow) let you see generally where the blocking and camera need to be placed within a scene. They help with scheduling (For instance, in that overhead above we would schedule shots 1D and 1F one right after the other since they are in the same exact camera position), but more importantly help make sure you aren’t crossing the dreaded 180 degree line (the dotted line between “B” and “D” on the couch. Basically if one shot is on one side of the line and the second shot is on the other side of the line, the people talking to each other look like they’re facing the same way and it’s confusing to the audience, but you’re not here for that lesson.)

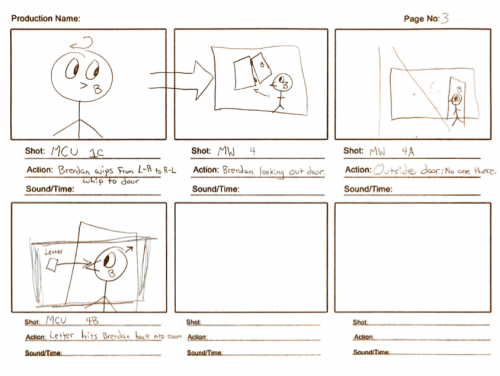

Then the storyboards all tie it together.

Even if they look like a 4 year old taught you how to draw and you didn’t take the lesson well.

Storyboards let you see a raw version of how each shot will look in terms of framing and shot size. With these three things, you will be able to know, well before you’re shooting a movie like your grad thesis, whether your chosen shots tell the story appropriately, as well as the way in which they are telling the story. Then all you have to do is shoot the movie.