At 32, I have finally learned how to write a paper. And it’s my thesis.

Maybe you are like me, and writing does ==+++””*****NOT*****””+++== come as naturally as it could or used to. High school fictional writing assignments—no problem. Everything that has ever required me to get to the point—complete failure. Like the kind where I will write an entire diatribe and it is perfect, read it a week after submission and it’s like looking at your texts in some kind of morning-after scenario. All that being said, I am extremely excited because I think I have finally, courtesy of my advisor Greg Foster-Rice (GFR), learned how I best write a paper. Like with a point, an introduction, and a conclusion. Which is just in time; it coincides with the writing of the longest paper of my entire life at 30 pages.

After 3 days of constant writing, this is what my smile looks like. I thought I was smiling.

What I have typically done is do a little bit of reading, find something I thought made sense, come up with a weak thesis and start writing. I’ll then throw in new thoughts as I go along, usually with about six to eight revisions. I’m also the type who will get an inspiration of some kind or another, write a few pages about that, and then push this inspiration to the end of the paper so I can maybe at a later date try and incorporate pieces or all of it into the paper. This creates a working document that is super messy and emblematic of the extremely messy way that I have come to write papers.

Before GFR though, my partner Michael (and Montessori school teacher par-excellence) suggested using the Pomodoro method of productivity, wherein you give yourself 25 minutes of work with 5 minute breaks four times in a row and then a 20 minute break. So I began with this.

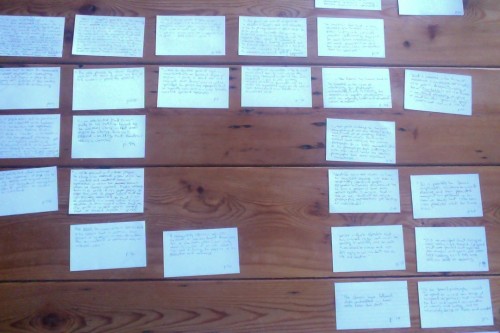

In GFR’s approach, you use index cards. I go through a lot of reading first with a stack of index cards, an envelope, highlighters and a notebook specifically for the paper. As I find useful quotes, I write them on the index card. Quote and page number on the front, bibliographic citation (or at least author, name of paper and date of publication) on the back. This process usually goes on for about two weeks. I have the notebook for all those inspiring paragraphs that would normally end up cluttering my rough draft paper. Eventually, I pick a day and just set all the cards down on a table and begin piecing together an argument based on my analysis of all the quotes.

I tried to zoom out as far as I could but this picture just looks better and you get the idea.

I then start making an outline with just the quotes on the cards. For instance, since my paper is looking at emergence and transcendence, I’ve made two layouts: one for transcendence and one for emergence.

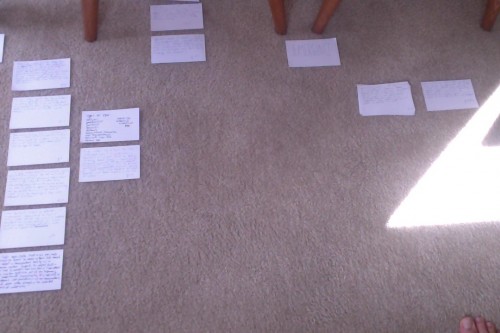

Transcendence outline is on the left, emergence is beginning on the right.

As I review these outlines, I start to get an idea of what the paragraphs that encapsulate all these ideas are going to say and can easily cite the authors and the words of the authors that stimulated these thoughts of my own. Right now I’m in the process of writing the actual paragraphs. Once I begin writing these paragraphs, it will be easier to attach them together as cohesive little lego building blocks of ideas, all accumulating toward a larger goal and purpose: a thesis statement that makes sense.

It’s enormously satisfying to finally have an approach to writing a paper that doesn’t result in total chaos, that doesn’t keep me up confused all night and, thus, fits neatly into my procrastinative tendencies to over-YouYube and placate with Facebook. Actually, I even lost my phone a few days ago, so I am no longer checking my Instagram and other social media sites every 10–30 minutes or so. TRUE CONFESSION. Social media applications are designed to get you hooked, which plays upon a weakness in human cognition, that of the addictive capacities of our dopamine reward systems.

When we do something fun or get positive feedback, our brain pumps dopamine through our receptors, which stimulates the feeling of “good” or “right.” Chocolate, alcohol, cigarettes, heroin, methamphetamine, roller coasters, high fives—all these things generate dopamine responses. Cell phones and movies have also been found to alter our brain chemistry toward these biochemical reward systems. What I have come to realize through this paper and through losing my phone is that I don’t want to be addicted to social relationships mediated by machines, and I want to write clear papers that effectively (and enjoyably) communicating my ideas fun.

I would like to say again, thank you GFR for helping with that. Thank you Michael for teaching me time management. Thank you divine light for transcending my relationship to technology, and thank you to the five minute breaks. This is how I spent them:

Eating cookies and stacking sugar in the missing location of the cookie.