To Look At You: Twenty Years of Self-Portraits

This year, I turn 36. It will be roughly two decades since the summer I saved up enough money from my job at the Dairy Crest (a local, seasonal ice cream shack complete with hand-cut curly fries, plastic aprons with drawings of hot dogs on them, and below-minimum-wage pay for the all-teenaged-staff) to buy my first camera. The technology was modest—a 4.0-megapixel point-and-shoot digital Fujifilm camera. As was the millennial way, my sister and I grew fond of blogging (or “online journaling,” as we called it “back then,”) and I desperately wanted virtual friends from band-related chat rooms and early social media sites (like Teen OpenDiary, then just OpenDiary, which predates platforms like LiveJournal, MySpace, Facebook, and YES, Instagram and now TikTok!) I have made routine the habit of photographing myself in my living space/photographing my living space to depict myself.

In my parents’ front yard, age seventeen; Bucyrus, OH, 2004

Growing up in a conservative, rural community without easy access to arts institutions, from an early age I developed a fond fascination with glamorous icons in film and music. When I trace the origins of these obsessions, I recall my private infatuations with how famous women like Monroe and Madonna proudly authored their own bodies and flaunted their overt sexualities on screen and in print. While family members looked on discouragingly, shaming them for “dressing and acting like whores,” I questioned the taboo surrounding their images and aspired to the fearlessness and self-assurance they displayed in their crafts.

Within a few months of getting my first camera, I taught myself two important photographic skills: 1. navigating self-timers, and 2. supporting/balancing my camera (tripod-less, of course) on various stacks of Rolling Stones and TV Guides and random flat surfaces throughout my childhood home. I tasked myself with creating images of myself resembling the alluring, powerful women I grew up viewing. One day, fooling around with some “selfies” (I wore different eye make-up combinations every day that, back then, warranted documentation), I sought out the window above my parents’ bed in their room. The ledge beneath the window, a shabby and soft wood (from accidental open windows during rainstorms) coated in chipped baby blue paint, became a favorite spot for me to set my camera, arrange a scene, fire the trigger, wait for the 10-second timer, and pose in a wash of diffused light. The background always softened into black. These early self-portraits demonstrated how consistently and creatively I problem-solved images, and they are early evidence of my preference for working with minimal tools. Simple, but effective. My philosophy in art is my philosophy in all things, or maybe just my life motto: “Make the most of what you have.”

By the time I was graduating high school and interested in pursuing photography more seriously, I took my Media Communications teacher’s advice and bought a 35mm SLR Canon film camera. It had manual controls, but I didn’t know how to use them. I still loved the experience of getting the film developed at CVS and discovering surprises and successes in my images. I used this camera to make a “portfolio” (I feel so embarrassed even calling it that) to get into the undergraduate Visual Communication program at Ohio University—where, I was told upon interviewing, that I would be a better fit (based on the constructed/posed element of my images) for the Commercial track rather than my original interest, Photojournalism. I didn’t consider “fine art photography” a pursuit for myself… the school of art seemed way too abstract in terms of a career path afterward. (I know now it’s only because no one ever demonstrated to me that it COULD be a path for me.)

I continued to make self-portraits, though I never know their ultimate purpose, after graduating and moving to Chicago, throughout my twenties (no matter my ever-changing living accommodations), working long hours as a manager in food service (prior to my return to higher education and applying to MAM in 2019). So, though my style of image-making and my thoughts about it have greatly shifted throughout the years, my core interests in constructing portraits, as well as using myself as a subject of the work, have remained the same for 20 years—over half my life. The pull to photograph my domestic surroundings is unavoidable for me—evidenced by years of almost-forgotten images on old hard drives.

View into my kitchen; Athens, OH, 2009

Bedding; Edgewater, Chicago, IL, 2011

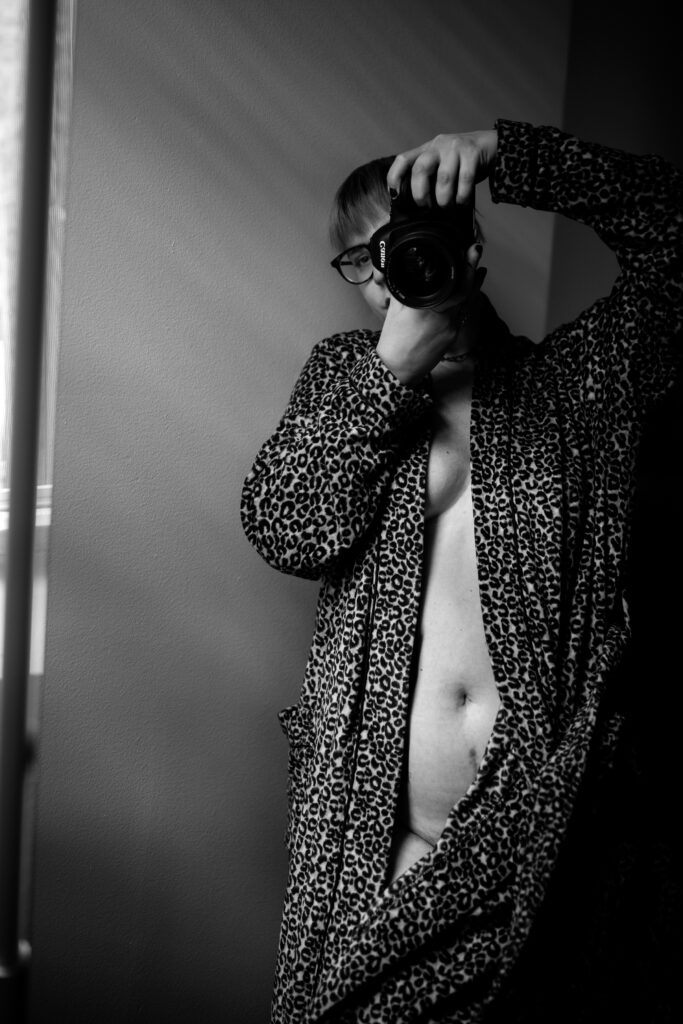

After a two-week-long hospital stay; Andersonville, Chicago, IL, 2015

Second time shaving my head; Andersonville, Chicago, IL, 2015

Although photography’s descriptive nature can illuminate us about others, it can also perpetuate reductive portrayals that further harm, rather than help, entire communities. Throughout visual culture, sex workers like me have historically been portrayed as a group of unnamed, naked, and shamed people—disguised, masked, or abstracted from view—or, as oppressed, damaged individuals living in the fringes of society, in need of saving. Photographs of sex workers function as conversations that shape societal attitudes and behaviors toward sex workers. Likewise, policies impacting their safety and livelihood are decided by individuals who have likely seen a litany of depictions. Yet, sex workers navigate what is known as the “whorearchy,” which reinforces that certain types of work are more socially acceptable (i.e., burlesque) than others (i.e., stripping or escorting). Regardless of their specific trades, sex workers of all kinds can face communal discrimination and abuse when their vocations are known, and images of them can perpetuate oppressive attitudes and behaviors.

Scar from removing my left ovary; Ukrainian Village, Chicago, IL, 2021

In images made in the last three years, I am exploring my interests in the performative nature of burlesque as well as the powerfully transformative powers of sex work and sexual performance for those who have experienced bodily traumas and struggles with their sense of autonomy. I show myself as a shifting, changing single woman (in preparation, dying my hair, or at ease despite adorning glittery, silver spandex), within the solitude of my modest city apartment. I honor the common artifacts of my experience and space.

Disco Sunday; Ukrainian Village, Chicago, IL 2021

Disco Sunday; Ukrainian Village, Chicago, IL 2021

Kitchen; Ukrainian Village, Chicago, IL 2022

Silk; Ukrainian Village, Chicago, IL, 2023

Throughout all my work, no matter the medium, my intention is to facilitate deeper understanding and critical conversations about sex workers to illuminate others, expanding representation of sex workers that ultimately shapes societal perceptions. Drawing from my own experience, I create these self-portraits in color and black and white and combine them with details and views of my living space to present a nuanced view of femme experience. My journeys in sex work and with my body are reflected upon within private interiority, highlighting the complicated and VERY internal impact of sex work on self-image and self-conception.

Theo and the morning light; Ukrainian Village, Chicago, IL 2021

I am drawn to exploring my roles in sex work and sexual performance with a camera because they, like image-making, foster unique risk-taking opportunities and create space for all identities and bodies to be fully seen. Within the rich community of sex work, I discover and work to reveal the vital narratives I endlessly encounter—including my own, as I entangle it in time.