The Bad Art Friend: Revisited

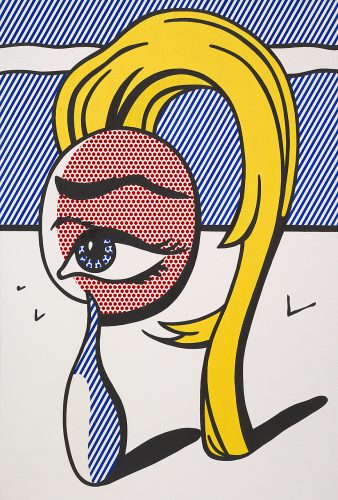

Lichtenstein depicts a woman crying happy tears— he takes inspiration from comics and other mediums.

I try not to look at Twitter during my busiest Tuesdays—I try, and I ultimately fail. During breaks from the classroom, I’m feral in my desire to be plugged in. I don’t want to miss anything of cultural significance. Thankfully, my Columbia professors seem to agree. Early in October, The New York Times released a piece that has since become infamous: “Who Is the Bad Art Friend?” The story revolves around two writers and one’s life story that becomes the other’s fictional reality. Basically, Dawn Dorland donates her kidney. Sonya Larson depicts a character who acts similarly, although, in her short story, this character’s intentions are clear: she’s a white savior, looking for attention.

This story is messy; it hits upon a deep-seated fear of writers, nonfiction and otherwise: whose story is mine to tell? We discussed this essay in one of my graduate courses later on and the conversation was so alive. Everyone had read the piece and had their own take on it, and even though this pop culture phenomenon was of-the-moment, our discussion was productive, poking at questions and anxieties that are almost timeless. How do we write the truth but with empathy? There was also talk of craft, as there is in most graduate writing courses. Larson is a fiction writer, but she uses pieces of a real letter that Dorland wrote and posted to social media—is this crossing a boundary, or because the story is fictionalized, does that negate any truth found within? Do we, as writers, owe it to our subjects to tell them what we’ve written?

Now in the second year of my MFA, I’m deep in the trenches of my work and people are starting to take notice. Before, when I would write to simply have it written, pen keeping me awake, trance-like in my need to get all the words out, it didn’t matter who got caught up in the crossfire. Or, maybe it always did, and just now I’m alert to the idea that not everything should be told. But, like most writers, I’m self-righteous about telling the tales of my pain —it’s mine, right, bestowed upon me anyway, shouldn’t I have the final say? I try to assuage my fears with the idea that I write the truth; author Anne Lamott proclaims, “If people wanted you to write warmly about them, they should’ve behaved better,” and in many ways, this is how I’ve chosen to look at my work in nonfiction. But even the truth is, at times, subjective. There will always be two sides to the story, however. Perspective is fickle, and memory is always impossible.

Lichtenstein further adapts his work, recreating his girls with tears in new and thought-provoking ways in order to give them new significance and perspective.

I choose, then, to think of an emotional truth that guides me. Likely, I won’t be able to recount every factual detail in my work, I’m no journalist after all, but I will try to be honest to myself and the way I felt about a situation. In each essay, I get closer to knowing myself and I consider myself on a path to discovery each time. Therefore, in essays about my family, I think about whose story I’m trying to tell: if it’s my own story, then I let the piece live. Similarly, if I’m writing to discover the whole picture, then I should allow my characters—people in my life that have been honest or even cruel to me—to languish in enigma. I cannot cast them as the villains just out of spite.

Honesty drives my work, and while I don’t know what to make of Dawn Dorland or Sonya Larson, I do know that the Creative Writing Program only gets me closer to my own, personal truths.