“Don’t Panic”

30 days to shoot day 1, anything that goes wrong feels a lot more consequential than something that went wrong 2 weeks earlier. It feels like there’s a lot less time to fix mishaps and get all of pre-production done. New elements like locations and casting come into play that you can’t entirely control. What becomes important, as a producer, is fixing problems as they come up, foreseeing some problems before they come up, and being prepared to do something about them. I’ve had to do some major reflection on how I deal with these problems.

On Saturday, a Nigerian filmmaker, Imoh Umoren, tweeted. “What are you going to do different this week?” I retweeted and added, “Not begin to mentally unravel at the slightest sign of something not going according to plan in pre-production.” He retweeted my tweet back and added, “Don’t panic.” And that pretty much sums up my strategy for the next 30 days. “Don’t panic.”

A brief twitter interaction between Imoh Umoren and I.

“Don’t panic” is probably an oral tradition in the film-making community passed on from generation to generation in a bid to keep the art form alive, because we all have that moment where we sit and ask ourselves, “Why did I choose to do this to myself?” It’s an age-old sign of empathy in this occupation. It’s also just really good advice. I have to remind myself that nothing gets done when I panic and that things going wrong are a trademark of low-budget filmmaking.

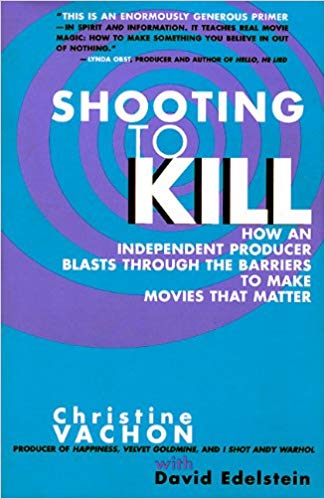

I recently read independent producer Christine Vachon’s book, Shooting to Kill: How an Independent Producer Blasts Through the Barriers to Make Movies that Matter where she gives the A to Z of creative producing.

“Shooting to Kill” by Christine Vachon

In the book, there’s a little section about the difference between a crisis, an annoyance, and a dispute. It was interesting to me that she thought it necessary to make this distinction because on page three of the book she literally writes, “A low budget film is a crisis waiting to happen.” So then, if, apparently, not everything is a crisis when making a low-budget film, what is? According to Vachon, a crisis is one of two things: someone getting hurt or someone being unable to shoot. Thinking about it now, I understand why Vachon felt the need to make that clear. If you think of everything as a crisis, you end up in a constant state of panic, and you can’t make good films when you’re panicking.

Vachon’s words come from the same place as Umoren’s. Written 20 years apart by people thousands of miles away from one another, but both incredibly impactful in helping this young filmmaker learn how to deal with annoyances and disputes better and know how to not panic when the crises do come.