Old Books

Part of the requirements for a Creative Writing MFA at Columbia College is to take two Literature courses. These courses are focused more on the scholarly and academic, and less on writing. Among other goals, these courses serve as a way to think about the reception of writing, and to get a sense of the literature in and around a genre. I currently am taking Victorian Illustrated Poetry, and last week, we got to look at and touch some books from the period.

Victorian Illustrated Poetry focuses on, as you would imagine, Victorian illustrated poetry. While both illustration and poetry had been around for a long time, the industrialization of the period allowed for books that included both to be mass produced and the blossoming middle class was a whole new audience ready and waiting for such tasty bits of literature. That’s the dry history bits, but what resulted was many, many books that set the groundwork for how we produce and read books today.

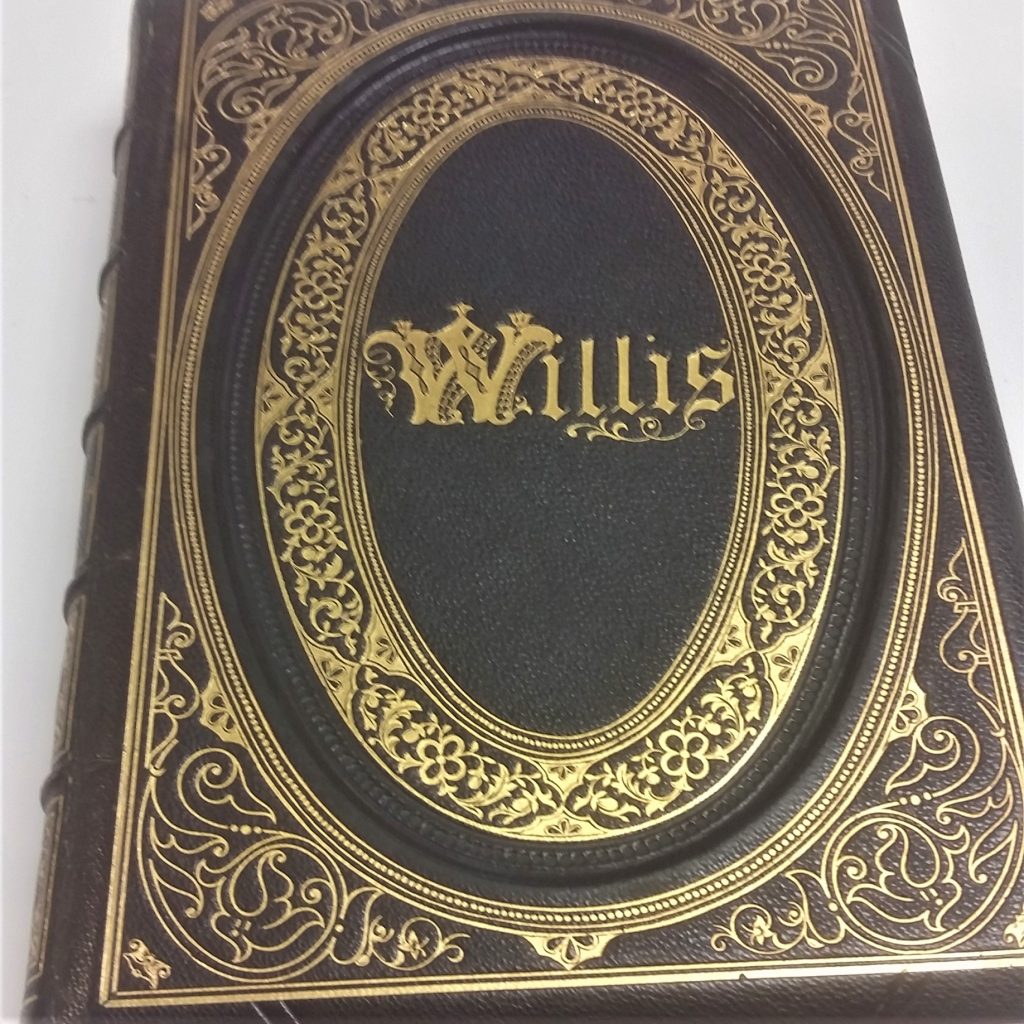

This book has a gorgeous inlay where the title is. The whole oval is a depression into the cover of the book.

Professor Ken Daley encourages us to think of these books as both text and image. This means reading both picture and words simultaneously, as they are placed together. The illustration influences the reading of the poem, and the poem influences the reading of the picture. While this may seem abstract, its something that the modern reader does everyday, albeit subconsciously. In our image rich world, we are constantly reading and consuming pictures and text. With every news article, Facebook update, Tinder swipe, ad on TV or online, and the list goes on and on. The Victorians started that.

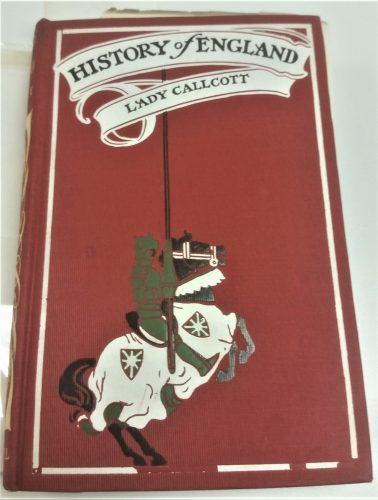

This cover is marvelously unfaded, with a rich and vibrant red.

Doug Wilson, a prolific book collector and seller, brought a huge collection of books in various conditions. He rolled them in on a cart, in printer paper boxes stuffed full. He started off by telling us that he got into the collecting because he wanted to be able to touch old things. These books weren’t behind the glass in a museum. They were passed around the room. We cradled their spines, carefully opened them up, and looked inside at pages that had been touched and read for well over 100 years. The sad part is that most of these books survived because they weren’t as beloved. Every time a book is touched, it starts to break a little, even if one is gentle. The oils in skin brown the paper and break it down. Opening it cracks the spine, loosens the glue. And yet, this breakdown of a book is something that I want for every single book that will have my name on it. Anne Fadiman has an essay titled, “Never Do That To A Book” in which she claims that there are two types of book lovers: courtly and carnal. The courtly treasure their books, never dog-ear pages, or crack the spines. The carnal devour them: they dog-ear, notate, spill coffee on, etc. The carnal will not leave books for Millennial Illustrated Poetry in 2117.

I’m ready. Let me learn.

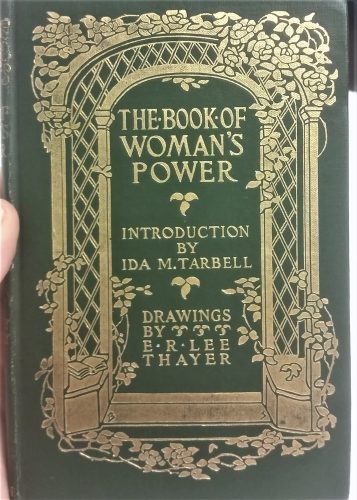

There was something magical about these old books. There was craftsmanship that went beyond a simple cover and a nice typeface. When these books were published, there were people who were dedicated to the design. Artists and illustrators worked together with the printers, who worked with the writers to create an object which would warm peoples homes with its content, and with its physicality. The book, then, became a vast collaborative object to be brought home to the newly educated middle class. A class of people who had previously been illiterate now got to have a rich object that would brighten homes and minds.

As a writer, it makes me a little jealous to see the craftsmanship in these books. What if my book could be published with that attention to rich detail? This class allows me to peek into the history of my own craft, and to understand where people like me have been in history.