Angry Arts Administrators

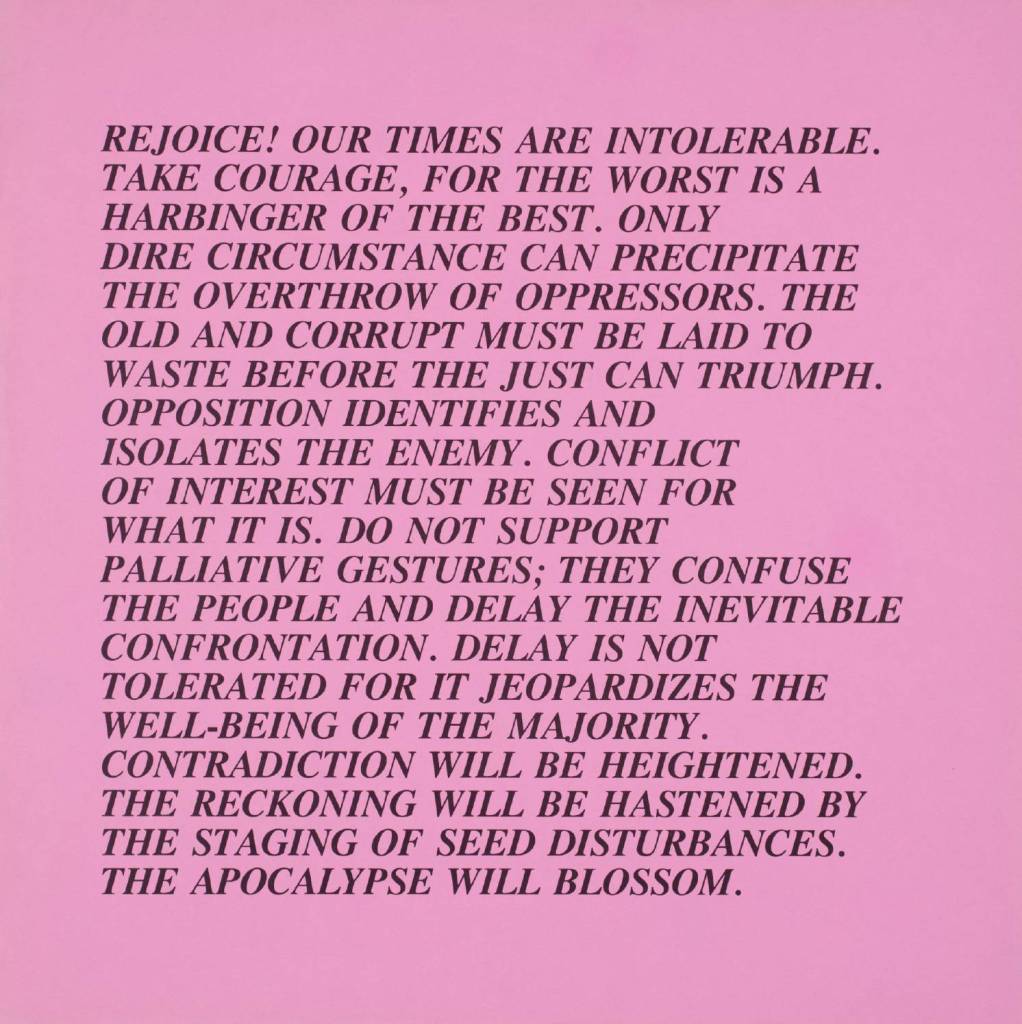

Jenny Holzer, Inflammatory Essay

I’m writing a blog post on a topic that is being mined the world over by writers more talented than me, with access to more stories than me, and with more training than me. But the topic is relevant here because I view it as inseparable from what makes a good arts manager—that’s right, let’s talk Harvey Weinstein.

I’m not bringing up Weinstein to outline the particulars of his offenses against the women under his sphere of influence over the years, although certainly that is a topic from which you cannot escape these last six weeks. I’m bringing him up vis a vis the master’s of Arts Management, specifically.

My decision to go into Arts Management is aligned with my desire to be a leader in the arts. The type of person who helps build the structures that ensure that artists’ voices are heard. A person who helps both create and determine the contexts in which art is received and experienced. In theory, the students of our program could rise to the heights of power in the arts and culture sector that might rival something like Weinstein. (I mean, that’s a lot of wealth and power we’re talking about here). And I view grassroots arts organizations as important as the behemoth film industry. When you build an arts organization from the ground up or come into a position of power within arts and entertainment, you start to have control over which voices are heard and how they are positioned. Managing and working with artists becomes about these dynamics. What Weinstein did was wrong because it took advantage of that power. He did not wield this power in good faith.

And this makes me angry. Like, Uma Thurman angry:

One of the things I’m grateful for in terms of my closest collaborators, peers, and faculty mentors here at Columbia College Chicago is that we are on the same page with regard to community and diversity.

Example: As I wrote about in our last session of Kelly Takes on the Topics: the events management practicum is hosting The Fresh Connect: a December 2 event celebrating the new Hip-Hop Studies minor. They’ve made the conscious choice to book people of color—artists and business owners alike—as part of the experience. Because it’s culturally relevant. Because hip-hop has its origins in the history of people of color and specifically blackness. Because it’s the topic and the time that these voices need to be elevated, and the time to devote these resources to this artform.

Example: My fundraising class centers on conversations about invaluable non-profits in Chicago that are doing work in social justice and community activism. Organizations include Girls Rock! Chicago (the nonprofit of my choosing), Public Media Institute (classmate Nick Rodriguez’s focus), and the Albany Park Theater Project (Rana Liu’s choice). These are the kinds of organizations that want to ensure a diversity of voices have platforms for their expression. These nonprofits have ideals that say—hey, sometimes you have to take a seat and listen to a different point of view from your own. Practice a little empathy about it.

So what happens when a person in a position of power uses that power in order to manipulate someone who is dependent on them in some professional capacity? Voices are silenced. The person harassed leaves a career. The person who harassed stays in their position of power. The dynamics remain unchanged.

What we have here, in this moment of mass reckoning for these men in the public eye, is a moment for CHANGE. The kind of change that I want to see with community arts organizations that bring neighbors to a greater understanding of one another. The kind of change toward which a conscientious arts administrator should be striving.

If it seems harsh that the Kevin Spaceys and the Louis CKs of the world are losing their contracts over allegations of harassment, abuse, or assault—that’s kind of the point. Their victims could not go on to be in positions of power. Their victims might not have been able to continue in their respective fields at all. This isn’t a witch hunt—no one wins when these allegations come to light and then men are forced out. As Kristin Gwynne says in the Cut: “What bothers me is that this moment, as good as it is, prompts the question: What are women getting out of it? I lost time. It affected my self-esteem and my ability to produce work.”

So what are women getting out of this moment? What are victims getting out of a public dialogue surrounding some of their most painful, vulnerable memories?

For this whole turning of the tide to not be entirely pointless, the tide needs to, you know, actually turn. The point is not protecting the careers of those who are served by insidious silence. The point is hearing, understanding, and listening. The point is giving the silenced a voice. The point is creating an entirely new playing field of equality.

From Beyonce’s Lemonade; envisioning this world with the tide turned, in like, a really grand way