“Your confusion is more interesting than your perceived wisdom.”

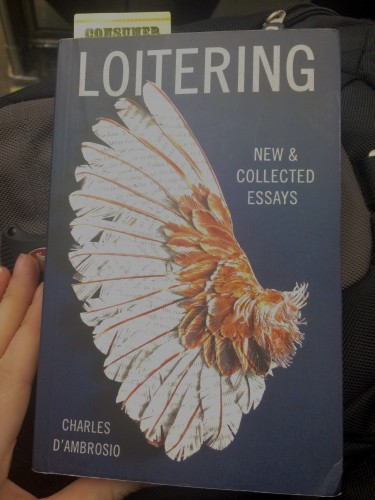

Loitering, Charles D’Ambrosio’s 2014 essay collection that includes pieces from the cult favorite Orphans as well as new works, is a book that came to me at the right time in my writing life. It was a time when I was going into new territory in my work and trying approaches that were out of my ordinary. I read Orphans my first year in the program and was immediately hooked on D’Ambrosio’s prose. It resonates even more strongly with me now after reading and re-reading Loitering as I have been this past week.

In some cases, the introduction or preface of a collection can be a dry and boring affair that satisfies questions about the source material or process of the author, but “By Way of a Preface” is lush in a way that is not ostentatious and rings full of insights squeezed from a life of reading and writing. He writes about the essay as a form:

“For essays were never a father to me, nor a mother—for essays were the work of equals, confiding, uncertain, solitary, free, and even the best of them had an unfinished feel, a tentative tone that made them approachable.”

The idea of uncertainty drives an essay, as it is an exploration. But as many writers who have taken part in workshops can attest, there are some workshops approached as purely problem-solving exercises rather than testing grounds for new work that embrace the lack of clear answers an essaistic exploration entails. In such cases readers may ask for too much as their human desire for clear and easily understandable answers takes over.

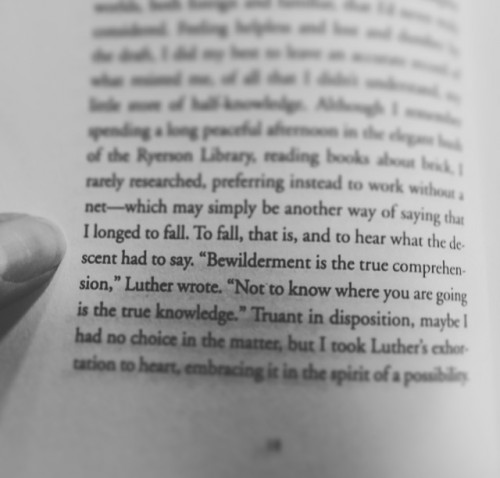

As a result, I can tell you that I have felt the pressure to make my essays “perfect” (whatever that actually means) and leave inadequate room for questions. D’Ambrosio shares this same foible and frustration regarding his early writing career with The Stranger, although his was slightly different than mine—his was (what I think of as) braver, a desire to “capture the conflicted mind in motion” or “represent failure on the move.” He embraced wrongness, discomfort, ignorance and champions it as a virtue of the essay.

D’Ambrosio has visited Columbia twice in my time here, once for a Q&A and reading as a guest author and the second time as a guest reader and as a leader of a workshop, where it just happened that one of my pieces was chosen to be examined in depth. Of course I was nervous. Of course at the time I wanted him to say it was beautiful and perfect, but that was my ego talking more than the writer that wants to perfect her craft. What I took away from the comments in our workshop was that I was too certain on some things and I wasn’t really digging into the component of ignorance—it seemed like the writer of the essay had everything figured out—so why was she writing?

Our vanity makes us want to appear smart to readers and to convince ourselves of it as well, but what “attempt” (a la Montaigne’s essasis) is there if the answers are all known and we do not grapple with them on the page for the reader?

During D’Ambrosio’s last Q&A with us, he shared an idea with us that has lingered with me and stuck in my head ever since: “Your confusion is more interesting than your perceived wisdom.” As I read and re-read his essays, and as I work on my thesis, I look for the places where he elevates his ignorance without destroying his credibility, where he is both a down-to-earth, regular guy but also a man who is deeply intelligent and analyzes the world though the lens of literature, memory, and a variety of less-than-typical experiences. Perhaps most importantly, he has shown me that ignorance is not always failure, and what looks like failure isn’t necessarily failure if it is expressed truly and honestly on the page.