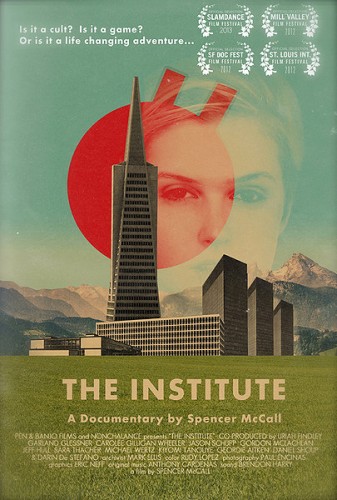

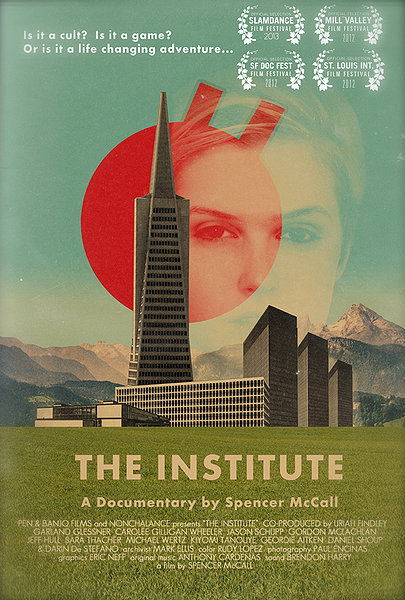

An Interview with Spencer McCall, Director of “The Institute”

Recently I posted a compliment on Twitter about the film The Institute. Through a series of fortuitous interactions I was able to get in touch with the director, Spencer McCall, and ask him some questions about the film itself, copyright, and the implications of the film for arts managers. The Institute is currently available on Netflix and features one of the most fascinating chronicles of a genre and media bending art experience. The Institute manages to transcend many aspects of capturing performance, game play and reality. For a more succinct description, I have included the Wikipedia entry for the film.

From the Wikipedia entry on the film

“The Institute is a 2013 documentary film directed by Spencer McCall reconstructing the story of the “Jejune Institute”, an alternate reality game set in San Francisco, through interviews with the participants and the creators. The game was produced in 2008 by Oakland-based artist Jeff Hull. Over the course of 3 years, it enrolled more than 10,000 players who, responding to eccentric flyers plastered all over the city, started the game by receiving their “induction” at the fake headquarters of the Institute, located in an office building in San Francisco’s Financial District.”

I asked McCall questions that I found personally interesting after viewing the film as well as some questions germane to arts management.

I highly recommend that you see The Institute if you haven’t already. A big thanks to Spencer McCall for being game enough to answer all of my questions thoroughly and eloquently.

Something that stuck out to me about the film is the blurring of the lines between reality and game. There were moments were I questioned the reality of the film, and in turn reality itself. The question here is, to what extent was this film a way of expanding on the meaning of reality?

When I started interviewing a lot of the more active members, or ex-members of The Jejune Institute, it became clear that the one shared experience they all had was the lack of having a firm grasp on the legitimacy of what was happening. Most thought it was something trivial, like a game or neat story told in a multimedia way. But there were certain elements of verisimilitude that suggested this was at least based on some events that happened. So in effect, The Institute is a documentary about how people perceive fictional narratives that are based on things that might or might not have happened… depending on whom I was interviewing that day.

Does the film seek to accurately capture the experience of the Jejune Institute or is it a way of taking the experience further? Both?

I did want the film to capture the tone of the experience, though I opted to go a little darker at times, simply because that’s more fun. I also wanted to discover for so many what the ultimate goal was. They question was always why does this exist? Most figured it was just some social experiment funded by a grant or a mystery investor to see what happened. But that wasn’t enough for me. I wanted to know the why behind the story that was slowly revealed to the city.

What was the filming process like? Gathering found footage, collecting archived material etc.?

There had been a lot of message boards and forums with people asking questions about and giving answers about the Jejune Institute. After it closed in April of 2011, and I got it in my head that I could attempt something that I thought would be special, I started reaching out to some of these people on the forums and asking if they ever shot any footage when they participated and if I could interview them on camera. The Nonchalance people caught wind of what I was doing and said it would be okay for me to make the documentary if I let them say their side of the story on camera as well. I agreed and they gave me a large amount of their own archival footage to work with.

When a work such as the Jejune institute starts to take shape, it seems like it would redefine the realm of copyright to some degree. There are so many people collaborating in the art, some of them at first unaware that they are part of the art. How does this redefinition play into the documentary?

Copyright was never something that the Nonchalance folks seemed too concerned with. The collaboration that they received from volunteer artists was implied to be owned by Nonchalance but no formal contracts were in place. That worked fine when you’re a nonprofit like they are, but when I started making the film, it became quite a burden of going through everything and requesting permission when fair use was not an option.

Were things licensed and contracted? Was the documentary created in collaboration with NONCHALANCE?

Nonchalance was very cool. They didn’t pay me to make the movie. It was to be my own project, and because of that, I was able to maintain all creative control. They gave me a huge hard drive of footage in return for interviewing them on camera. But as far creating the film, I was left to my own devices.

I guess the heart of my question here is with so many collaborating artists does ownership start to disappear? And if so, what is the result?

Collaboration is great. It’s super important to understand how different people will interpret whatever you’re creating. If Nonchalance had made their own documentary, they knew that at best it would be a vanity piece and at worse it would still be in production. Allowing me to be autonomous and independent allowed me to make the film in a year, as opposed to three years if there had been more chefs in the kitchen.

What was the most difficult thing about building the narrative for the documentary?

The most difficult thing about making this documentary was how esoteric some of the subject matter was. It required knowledge of 70s pop psychology and new religious movements and then the punk rock and hip-hop scenes. The Jejune Institute was a project that unfolded over three years in five acts. And there were about three years of story to be told. So figuring out what to cut without losing the tone and integrity of the project was constantly difficult to reconcile. Delta Particles are a good example; so interesting, but ultimately so unnecessary.

What can theater artists and managers learn from NONCHALANCE?

Theatre artists and managers can maybe learn from Nonchalance that it’s not only easier to ask forgiveness than permission; sometimes it’s the only way to get anything done. They never accepted an excuse for something not being possible. If I had asked permission to make this documentary before I started, it would have never been made.