What the hell, Tuesday!

[flickr id=”8168895047″ thumbnail=”medium” overlay=”true” size=”original” group=”” align=”none”]

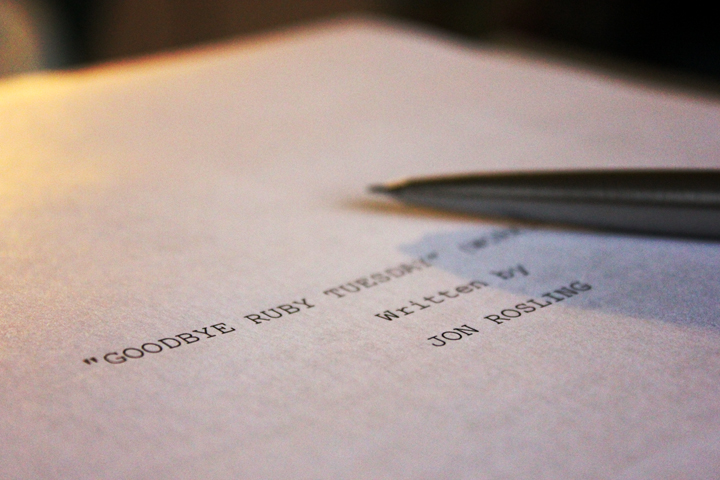

‘Karen requests that we all bring our laptops to class on Tuesday’, Joe’s email read. This should have triggered some suspicion, but in the face of the clusterf**k of work us producers are subjected to at this stage of the semester, the email was read without much questioning and, soon after, cast aside.

Take a walk through the film campus right now, and you’ll sidestep rogue film crews and endless amounts of actors waiting for auditions and rehearsals. The first floor is filled with casual production meetings, as producers, directors, assistant directors, production designers, and cinematographers fight for the few wall sockets that remain. It’s Columbia’s season of high production, but amidst the filming, we still have our classes to attend. Last week’s Writing for Producers class made for an interesting start to a day that will forever be remembered in my books as ‘What the hell, Tuesday!’

In filmmaking, script coverage is a tool used for the analysis and grading of a screenplay. It most commonly happens within the script development department of a production company. I have read that the Writer’s Guild of America registers somewhere between 35,000 to 50,000 scripts a year. As you would expect, studio executives do not have the time to read this many scripts, and so that’s where coverage comes in. It generally takes the form of a four-page written report. There’s an industry standard template to follow, which involves preparing a detailed coversheet, writing a logline, a one-and-a-half page story synopsis, an analysis of the screenplay’s potential as a film, and a comment summary. It’s by no means an easy task, but a skill that will serve a producer well.

[flickr id=”8168925196″ thumbnail=”medium” overlay=”true” size=”original” group=”” align=”none”]

The last two times we prepared coverage for our Writing for Producers class, our professor Karen provided us with screenplays that are currently in production in Hollywood. It takes a bit of time to get the hang of, but we had the best part of a week to prepare the coverage report. You start by reading the script through, preferably uninterrupted, to get a clear understanding of story. Ideally, you read it again, but this time making notes along the way. Finally, you set about writing the four-page report. That was the method and timeframe we had become accustomed to. Tuesday, however, was a different ball game.

You know that look on someone’s face when they are about to screw you over? It’s somewhere between trying to stifle a far-too-eager smile, but it’s given away by a devilish glint in the eye. That was the look on Karen’s face as we tentatively took our seats. The clock struck 9am, and with a thud, fifteen feature length screenplays landed on our desks; ‘Coverage… Three hours… Go!’

What the what!? It felt like one of those do-or-die moments. With one-hundred-and-eleven pages of fresh story before us, and a loudly ticking clock above us, there was barely time for fretful glances before diving in. The furious clacking of fifteen keyboards made for a rhythmic soundtrack that brought me through the next three arduous hours. Midday came at a reckless rate, and whatever state our coverage was in, it was submitted. A collective sigh—though, I’m not sure it was relief—swept across the room. Now, we all looked at each other, in a what-the-f**k manner. Words were not even necessary.

[flickr id=”8168927794″ thumbnail=”medium” overlay=”true” size=”original” group=”” align=”none”]

It’s how it will work when we get to LA, Karen assures us. Someone will throw a script at us in the morning, and want a coverage report on their desk before lunch. Meanwhile, there will be a dozen other things still to do, and the phones will loudly continue to ring. ‘Get used to it’, she said.

Leaving the classroom, I gave Karen three hours to grade the reports. That showed her.