INTERVIEW WITH A PROFESSIONAL – STEVE ALBINI

STEVE ALBINI -AUDIO ENGINEER – MUSIC PRODUCER – MUSICIAN

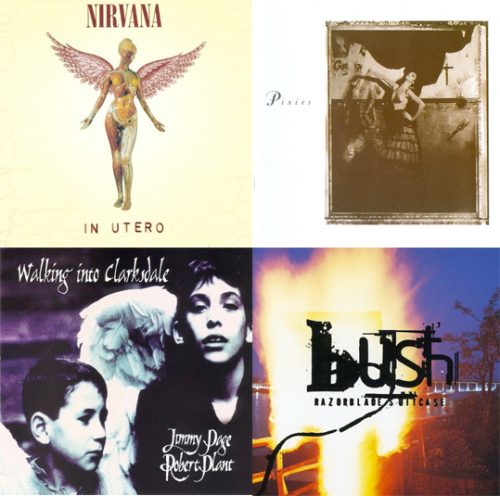

The In The Loop staff recently had the opportunity to interview music legend Steve Albini. Famous for producing and working with bands (although he prefers the term “audio engineer” due to his hands off approach) such as Nirvana, Robert Plant and Jimmy Page of Led Zeppelin, The Pixies, PJ Harvey, Robbie Fulks, Scott Weiland, Bush, and The Stooges (just to name a few). Steve estimates that he has worked on well over 1,500 albums. Aside from his career in audio production, he is also an accomplished musician in the bands such as Shellac, as well as a former music journalist.

Originally a bassist, Steve turned to his life of music when he was roughly 14 years old after being introduced to punk music and bands like The Ramones. Steve manages his studio, Electrical Audio, which sits in Chicago’s Avondale neighborhood. It is a massive industrial space that was a former facility for Bally pinball company among many other things. It’s hard to imagine any individual who’s lifestyle, contributions, and connection to music could surpass the path that Steve Albini has walked.

Steve sat down for a Q&A to talk about what things students might face in today’s world and making a name for oneself in the industry.

In The Loop: What are your thoughts on Chicago’s musical history and the current scene.

Steve Albini: The music scene in Chicago has always been very cross pollinating. In the post-punk period, a lot of the bands that sort of cut their teeth in the punk era started interacting with the jazz music, and the free music, and the improvised music scene. There ended up being a lot of cross-pollination. There were house and dance music producers and people who cross-pollinated with some of the jazz and rock people. There are these hybrid tendrils that extend into all these different scenes in Chicago and I find that quite invigorating.

Chicago has big advantages in that regard. You can see different styles and types of music and interact with different kinds of people and maybe even get them involved in your projects. Everyone is very fraternal and very supportive.

There’s not a lot of bloodthirsty competition in Chicago. In places like New York and LA the cost of living is so high and the the notion of “industry” is much more cemented. In LA there is a pop music industry, in New York there is a pop music industry, and there’s competition to be part of that. The competition to beat other people to the brass ring or whatever, and I never get that feeling in Chicago.

ITL: What are your thoughts on living in Chicago regarding the music business?

SA: There are a bunch of natural advantages to living in Chicago if you want to make a living as an engineer or in music. Chicago is a central location. It’s like smack in the middle of all the population centers in the country. If you’re in a band you can do weekend trips where you can play two or three cities out of town, come back and still go to work on Monday morning.

If you’re a recording engineer, that means that there are local musical scenes all around you that may need help. You can be a resource for all of those people and eventually you’ll have a larger much larger pool of interested people that can form your client base.

Chicago is also an industrial city. There are big empty buildings around that were formerly industrial buildings, that can be repurposed as recording studios, or work and live loft type spaces. There’s a lot of semi official or informal or downright illegal places where people can live and work and record and put on shows and that sort of stuff.

Another nice thing about Chicago being an industrial city is that you have resources available. There are lumber yards where you can get materials in your van to build the loft or a practice space or whatever.

ITL:How did you go from being a musician to getting into recording music?

SA:That was a very natural transition for me. I have been in bands continuously since the late 70s. When you’re in a band, eventually your band wants to make some recordings of itself, so that you can hear what you’re working on played back to you. So you can evaluate it. That fell to me and I developed a rudimentary set of skills in recording. Once I had those rudimentary skills then I became useful to other bands.

The first impulse was to record my band which was basically just me and my friends f*cking around. From there I made myself available to other bands to record, so that they could hear themselves. My peer group and my circle of friends eventually widened to include their friends and their associates. Eventually some of the things that I recorded got released in some fashion. People who were sort of secondary or tertiary relationships with those people were like, “Oh yeah I had that, I thought it sounded good, we need to do a demo. Can you do our demo?” When records started coming out it was, “Oh yeah, I heard that record, I like that record! Can you do our record?”

Eventually I was getting enough work as an engineer where I was able to do it to charge enough for it that I could make a living at it. I quit my job and I concentrated on being a recording engineer full-time as a profession.

There was a span of about eight or nine years from when I first started doing recordings until I was able to do it as a profession. Eight or nine years, I mean, I could have gotten a medical degree in that period of time. So there’s a long arc where first you’re doing it because you’re interested in it, then you’re doing it because other people are interested in having you do it. Then you discover that you can make a living at it, and then you’re doing it professionally.

To get from the beginning of that process to the point where I could support myself took a very long time. I don’t think I could have done it faster. I could have done it faster in a sort of telescope sense, but if I had done it faster I don’t think I would have been competent by the time I eventually started relying on it as a livelihood. It takes a very long time to get from being someone who does recordings casually to being skilled enough and have a client base enough that you can do it for a living.

I would advise people who are doing that, who are on that path as a career, not to be impatient. I have been doing it for a very long time. The significant part of that was me learning the trade, learning how to solve problems, learning how to deal with other people and their creativity and their egos and their sensitivities and all that sort of stuff. If I had tried to do it any quicker I think that would have been clumsy enough at one or the other of those skills that it all would have fallen apart.

ITL: With all the people that you’ve worked with in the past, or are currently working with, what are traits that you see in some of these people who are consistently achieving “success”.

SA: There are two ways to define success. One of them is to achieve certain material goals, like I want to be able to make a living at this, I want to be able to buy a house and put my kids through college and blah blah blah. That’s one kind of success. When you’re talking about something like music, from my perspective the success is being able to do it. If you can continue to make music for your entire life then you have been successful.

One way of thinking about it is that music is sort of like dancing or painting or bass fishing or ballroom dancing or playing chess. These things are rewarding to do. Just doing it is satisfying and rewarding. A vanishingly small number of people do that professionally. There are only a very very few professional ice skaters. But a lot of people ice skate and a lot of people love it.

That you can keep doing something that you love is an extraordinary success. It’s not a trivial thing, something that animates you and excites you and it gives you meaning to your life, that you can do that every day. That’s not a small thing at all. I would say that’s the most important thing, that you get to keep doing it . That is how I would define success as a musician.

There’s a guy named Robbie folks who was one of my very first clients. I started working with him 30 years ago. When he started out he was in a pop rock band. That band kind of fell apart. He played bluegrass for a while and he started doing more serious country music. The sort of singer/songwriter music that was associated with country music but not strictly country. Now he sort of settled into an acoustic style of music that is uniquely his. There very few people operating an act in the idiom specific to the way he’s doing things.

I’ve worked with him here and there throughout this whole long career. He’s now a grandfather, when I first met him he was like a recent college graduate and was an intern at a law firm. So he’s been doing this for his whole adult life last year he was nominated for two Grammys.

If you listen to the album that was nominated for the two Grammys and then you go back through his career and listen to all of his other records it’s not like he finally made a good one. It’s that people finally caught up to them all of his records are good.

ITL: If you could give a message to yourself when you were first starting out, what would that message be?

SA: I think the most important thing is to maintain your identity. The thing that makes you unique. The thing that makes you someone’s choice over someone else, that thing that makes you distinct as an individual. Hang on to that. What makes you a distinct and separate person is the specific thing that is going to make other people want to work with you. Stick to your guns. You will find other people that think like you do and you can stick with those people . You don’t need to accommodate the fickle tastes of the rest of the world.

Find people that think like you already. Don’t find people that you disagree with and try to argue them into your position. Don’t put yourself in a situation where you disagree with everybody you’re working with and hope to bring them around. Don’t try to engineer other people in that way.

Find like-minded people and stick with them. You won’t have to explain yourself, they’ll understand you intuitively. That way you won’t be wasting your energy trying to convert each other into something. You’ll just carry on naturally going in the same direction because you were headed in the same direction to start with.

Being a musician, playing music, being an artist of any kind, being a creative person of any kind,

that’s a very satisfying thing to do. Most of the satisfaction of doing it is in doing it yourself. If you are only willing to do it if people pay you, then that’s not probably not your natural calling. If you are only willing to do it for money, then you don’t love it enough to put up with all of the hardships that come along with choosing that as a life.

People like what they like. You should make music that is satisfying to you. You should be involved in projects that are rewarding to you for their own sake. If other people respond and if it resonates with other people then you will have a measure of this other material success. But if not you should still be doing things that are satisfying for their own sake.

I have been surprised at every stage. I think if I had had expectations like when I first did my first recordings, like I want to be doing this full-time in five years, I would have been disappointed by that expectation. When I first put a little modest home studio together, if I had said to myself “Allright, I want to have a a full-on two studio facility in a couple of years”, I would have been disappointed.

I think it’s been very crucial for me not to have goals and not to have expectations of achieving goals. I have avoided an enormous amount of frustration because every step of the process took a very long time. The only way that I could be satisfied with it was if I was satisfied at every moment. That’s intimately satisfying for its own sake.

Then you wake up one morning and you realize, “Oh I have a recording studio, I have been doing this for 20 years”.

ITL: If a space alien came to destroy Earth and it noticed your studio, Electrical Audio, and it asked you what exactly your studio is, what would you tell the alien?

SA: It’s a place where music was recorded for the future. In the same way that there are those cuneiform tablets that have the earliest writing in the Aramaic or whatever language it is. There are these clay tablets that have words and descriptions of everyday life written into them. Those have been preserved from thousands of years ago. Electrical Audio would be the equivalent of the wooden stick that they used to make those impressions.

We are a tool that was used to make recordings. Hopefully the recordings have survived even if this place doesn’t survive. We are not the tablet itself, which is the information, which is the historical artifact and the object. And we’re certainly not the meaning of the words that are written on the tablet. We were the place where people could do that. Where they could make a recording of something that would outlive them. Presumably their creative enterprise would gain its final form here and then it would be preserved forever.