Winterlines

L. was a human palimpsest. He sat with his cane in the front room of the pub, near the bay window, at a wooden built-in made for two. He nursed a half-empty pint of amber with his crooked hands. Tiny broken blood vessels framed his mouth. He still had the mien of a larger man but his carriage was wrong. The lapels of his anorak sagged where they should have extended, and where there should have been some sort of trapezius, there was a hollow. The metamorphosis was clear: L. had been rewritten.

“Put your money away,” she said.

“Nora—I pay as I always paid,” he said.

“Your money’s no good here, it’s just nice to see you out.”

“I’ve enjoyed my night immensely.”

“Don’t pick up any girls on the way out, mind.”

L. managed a smile. “Night, Nora. Thank you for everything.”

Once home he climbed, slow as a clock’s hand, to the second floor. Upstairs he removed and carefully folded his clothes, found his hot water bottle and went to the toilet. He had not flushed from the time before and everything had congealed.

L. stayed sitting up in bed to support his withered neck. He recited a poem by Ovid. When finished, he tucked the hot water bottle between the frayed grey blanket and flat sheet and folded his wrinkled hands one over the other. A few flies rapped against the dark bedroom window; the new moon wasn’t visible. He stroked his translucent skin, the islands of spots that merged into one continental mass, the knotty tributaries of veins, the craggy peaks of knuckles. L.’s hands had been replaced.

He heard her old Astra slow down outside, its door open and close, and the click of footsteps coming up the walkway.

“Morning, Dad. Alright?” she said.

“I’m in the sitting room, Fiadh,” L. said.

Fiadh peeked around the corner. “Why are all the blinds down?”

“I was dancing naked.” He frowned. “You look like Maggie Thatcher.”

“Oh, wonderful. Hopefully when she was alive? I’ve had my hair done. Mrs. Denison says that she saw you yesterday, quite late, on the way back from the pub.”

“I will have to remember to change my route. And you wonder why the blinds are down. It was March 20, so I stayed and had an extra pint for Saint Cuthbert’s Day.”

“Finally, spring. Are we still on for the cathedral procession day after tomorrow?” Fiadh removed her fox-brown overcoat and yellow and white silk scarf, and hung them on the single hook in the dim hallway. “She thought you seemed shakier last night. With a bag—was it from the grocer?”

“I was so tight I don’t remember, maybe you should ask her.”

“I said ‘you should see him, he still does his own washing up’.”

“Don’t make it sound like I’ve just done the splits. I thought we could sit in here, for a change.”

“She was only looking out for you. It’s chilly in here. Did you see the eclipse yesterday morning? The path of the shadow went around Greenland and crossed the North Sea. Oh, Maeve’s going to call you.”

“You’ve been talking to Maeve? It’s not her birthday until June.”

Fiadh sighed. It took her only one step to cross the parlour. She bent down to adjust the knob on the small ceramic gas heater bordered in sea-green tile, and sat down beside him on the abraded settee, playing with the threadbare end of a tissue stuffed into the cuff of her blouse. “Yesterday. Everyone’s fine. She’s going to try you today. ‘Not too late in the afternoon,’ I said, so morning her time. So as I said on the phone, I’ve just come round to chat a bit.”

“I assume about Sherburn House, since that’s all anyone speaks to me about anymore. I expect you’ve decided it’s time.”

“Billy says when he came round yesterday you wouldn’t speak to him.”

“Why do you all have keys to my house?”

“Ignoring him or chaining the door isn’t helping.”

“He put his foot down, there’s nothing more to say. I’m not entertaining it. He said he would not come back and plead with an old queer.”

“Well, seeing you’ve just told us about yourself, it’s been a shock for him.”

He swatted the air. “And he finds any excuse to punish me. Seems I raised quite the Calvinist. And now I can’t have an untied shoelace without him scheming to get me into that place.”

“We only want what’s best for you. You can’t manage alone.”

“I manage fine.”

“Dad, you can’t live here by yourself anymore. Look at your hands, they’re seizing up. I’ll go make some tea. We can’t be on-call day and night in case something happens—”

“In case, in case; nothing has happened,” he said. Fiadh got up and moved down the narrow hall toward the tiny kitchen. The walls were bare save for a small, round clock that had stopped just past 3. L. struggled to get up, but quickened his pace and followed closely behind. “Don’t go back there, I’ve been busy scrubbing and I’m not done—and the back is off-limits, something died in the shed over the winter and it’s rotting now.”

“This teapot is chipped,” she said. “I’ll get you a new one. And you haven’t replaced the sponge in months, it’s black.”

“It’s black from washing out the teapot, which pours fine. I’ve had it for thirty years and it’s been chipped for twenty. Or haven’t you noticed until now.”

Fiadh rummaged through the cupboard and pulled out a pan. “What’s this doing tucked back here? It’s charred. Dad, the handle. What’s burnt on the bottom—it’s rock-hard?”

“Creamed corn. So I forgot to clean it, don’t make it into something.”

“You left the cooker on. Was it when you went out? Or when you went to bed.”

“I’m not going to that Victorian dungeon.”

“It’s completely remodeled.” Fiadh tossed the pan on the laminate counter, walked over to L. and patted the back of his shoulder. “We’re seeing it at lunch, after the cathedral. They are happy to have us for the day. Both of us can come with you, I’ll talk to him, or it can be just you and me. It’s time, Dad. I’m sorry.”

“What do you know about time?” He shook her off. “You were smaller than I had imagined,” he said to her, the corners of his mouth drawn down. “Not quite human.”

“What?”

“When we met after the war.”

“Oh, yes. I’m sure.”

“And look at you now, giving the orders. You think I go to the cathedral to listen to those zealots? They’re all teched. I saw plenty of graves—and more than enough clergymen—as a young stonemason. Even more in Italy, in the war.” L. searched the floor, bewildered.

“I understand it’s difficult, Dad.”

He turned to her, clutching the apron of the wooden table. “I go to remember Patrick Alington.”

“Was he a special friend?”

“Are you unhinged? He was my commanding officer, captain in the 6th Grenadier Guards.”

“I assume there were some,” she sighed. “You haven’t told us about any of those yet—”

L. slumped down at the table, cleared except for a neatly folded pile of used wrapping paper. “Before you leave, I want to tell you something. Stack and seal slab stone; you think it’s impervious, Fiadh, but the shit’s still underneath.” He glared at the flies knocking against the back door window. “After the landing at Salerno, I saw something I have never forgotten. Working men were used as scouts, cannon fodder. German defensive lines stretched across the Apennines, meant to stop our advance over the mountains. Patrick and I became separated from our division north of Naples at the first line—the Volturno Line—with an entire panzer division holding the hills. He died right beside me, September 24, 1943. The back of his head was blown apart by a mortar, but if you laid him down, you’d never know. You would have been two at the time.”

L. knitted his brow and eyed the burnt pan. “I buried his body on a sweltering day under brush, then fled into the mountains to find cover; as high as I could climb. Forty-six days I was stranded between enemy stations, foraging—forty-six nightfalls in the mountains, starving. My division found me in November, crouched in a crevice outside an abandoned village, well behind the second Barbara Line. We then had to break through the final Gustav Line; we dug in at that line for the winter. It was the most impenetrable.” He rubbed his hands. “But first we went back, removed the debris, exhumed his body. He was there, just as he’d been the day I left him, but his limbs were still flexible. His flesh had not decomposed. He looked asleep. They assumed delirium, combat stress; that I had the date of death wrong.”

“I don’t know, Dad, it was seventy years ago,” she said. “I know how important friends are to you. Especially, I mean, for men like you.”

“I was still a journeyman when I left,” he said. “Then after, when I became a master, I was approached to rebuild the nave of the cathedral, including Saint Cuthbert’s shrine. I offered my services for three years. It was there that I learned about incorruptibility, the translation of relics. Eleven years after Saint Cuthbert’s death, when they first moved the body in 698 through the snows of Northumberland, they discovered it hadn’t decayed. Whenever they moved it over the centuries, they always found the same thing: an intact corpse.” L. shook his head. “I know what I saw under that debris, Fiadh. When I go to the processions I remember him—unscathed—being pulled out from under the mound of dead thicket.”

L. tried to right himself. Fiadh moved closer, but he held his gnarled hand up to stop her. “About the century that has passed, Fiadh, I don’t have much else to say or care. I’m sorry if that hurts you. I remember long ago and I remember this morning. In between, there is absence. Every night waking up in the dark, immured. The fear hovering just above. The shame I built around me, with my own hands.”

He met her gaze head-on. “You think you know everything, what’s best and worst, what’s bearable and unbearable. There are many lines in life you can’t find a way to cross. Impassable, unnavigable. So here at the end, I wanted to cross one, and tell you who I really was, without shame. And all I get is more from you.”

She lowered her head. L. stroked his temples squeezed his eyes. “If I could do it all again. Rewrite my beginning and middle, but I can’t.” He turned back to an empty window—the flies had gone.

“I can, though, write my end. I had no ‘special friends’ as you call them. Assure your brother. I may as well have been invisible.” He looked down at his legs. “And now, I almost am. I can barely hold a glass. I am drifting into decline, Fiadh—my time’s run out. I won’t see another winter. I walk like a penguin, my hair is almost gone and my legs don’t carry me. I’ve never had much. But I get up. I feed and clean myself even if it takes me all day because that’s what I’ve always done. I can’t hold a book anymore but I can recite all the poems that I studied as a young man.”

“Dad, I know you’ve always been independent. I know you don’t want to go.”

“So don’t speak to me of that place! Not today. Come back the day after tomorrow. I promise we’ll go on the way back from the cathedral. Just no more now, alright?”

“It’s for the best.” Fiadh put her coat and scarf on, sorted the lapels and checked the back of her hair. She glanced back at the pan on the counter. “You rest. Remember Maeve’s going to call. We’ll go over the details on the way. I’ll pick you up. Is ten alright?”

“Of course, my little one.”

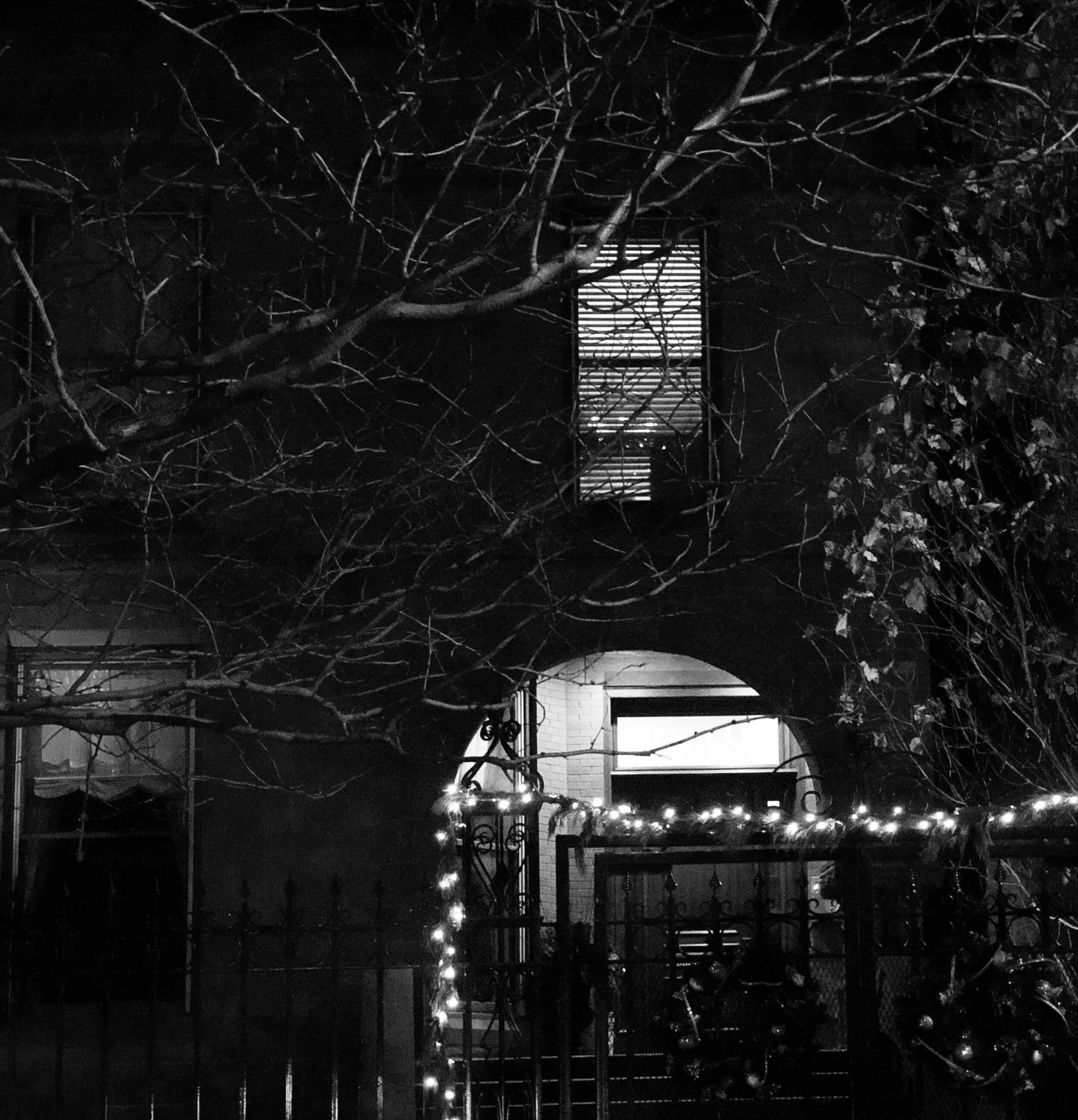

When night fell, L. latched the door. The blinds remained down. He fixed himself some instant porridge so his stomach wouldn’t be empty and made his way up the stairs. The thin edge of the moon shone low in the sky. He removed a pen and a piece of worn, almost transparent, paper with some faint handwriting on it from the drawer. With his crooked hand he carefully wrote one sentence in dark ink over the faded script: I will neither change, nor move, nor cross over.

L. took the empty glass from the table and filled it in the washroom sink. He found the bottle, but struggled with the cap. He managed to pry it open, swallowed several pills, and tucked himself into bed.

He dreamt of headland streams that tumbled over burnished stones, streams that transformed into tufa-lined rivers, carving ever deepening fissures into the rock face. Deep pockets of woodland dotted the mountains—their highest peaks still ringed with fir trees—and descended into forests of beech; the smell of chestnut, birch and juniper wafted up to where he squatted alone by the steep pass. Hectares of scorched holm oak had been razed in the southern valley. He dreamt of shale and sandstone; metamorphic, calcareous outcrops of white marble formed from limestone that stretched in a band from the Campanian volcanic arc behind him all the way northwest to Rome. He saw stars in the east glinting over cliff sides; charcoal silhouettes transmuted into pale basalt and silvery splinters of granite. The weak light gained momentum. It seeped up from a hidden point below, broke through the thick mortar smoke and formed a winterline, concealing the horizon yet haloing the camber of the hills in lilac. L.’s breathing was laboured, his cheeks were sunken, but he watched that strip of light between the darkness above and below, and believed that against every odd, by luck or by a miracle, he would not die.

Ellis Scott is a new writer, and an old man. His first story “Levies” was published by Into The Void magazine in 2019 and his second story “House For A Young Man” will be published by Yolk in 2020. His work has also appeared in Blank Spaces, Meat For Tea and High Shelf magazines. He is nominated for the 2020 Pushcart Prize.