Four

Death gave me his jacket today, the all black one with the stylish leather body and cotton hood. “Times are changing,” he says, “and I am anything but outdated.” Death goes by Maurice–Maury if you’re cool–and Maury defines fun as screeching tires marking up curbs. Light speed, Godspeed, he drives like he’s racing both.

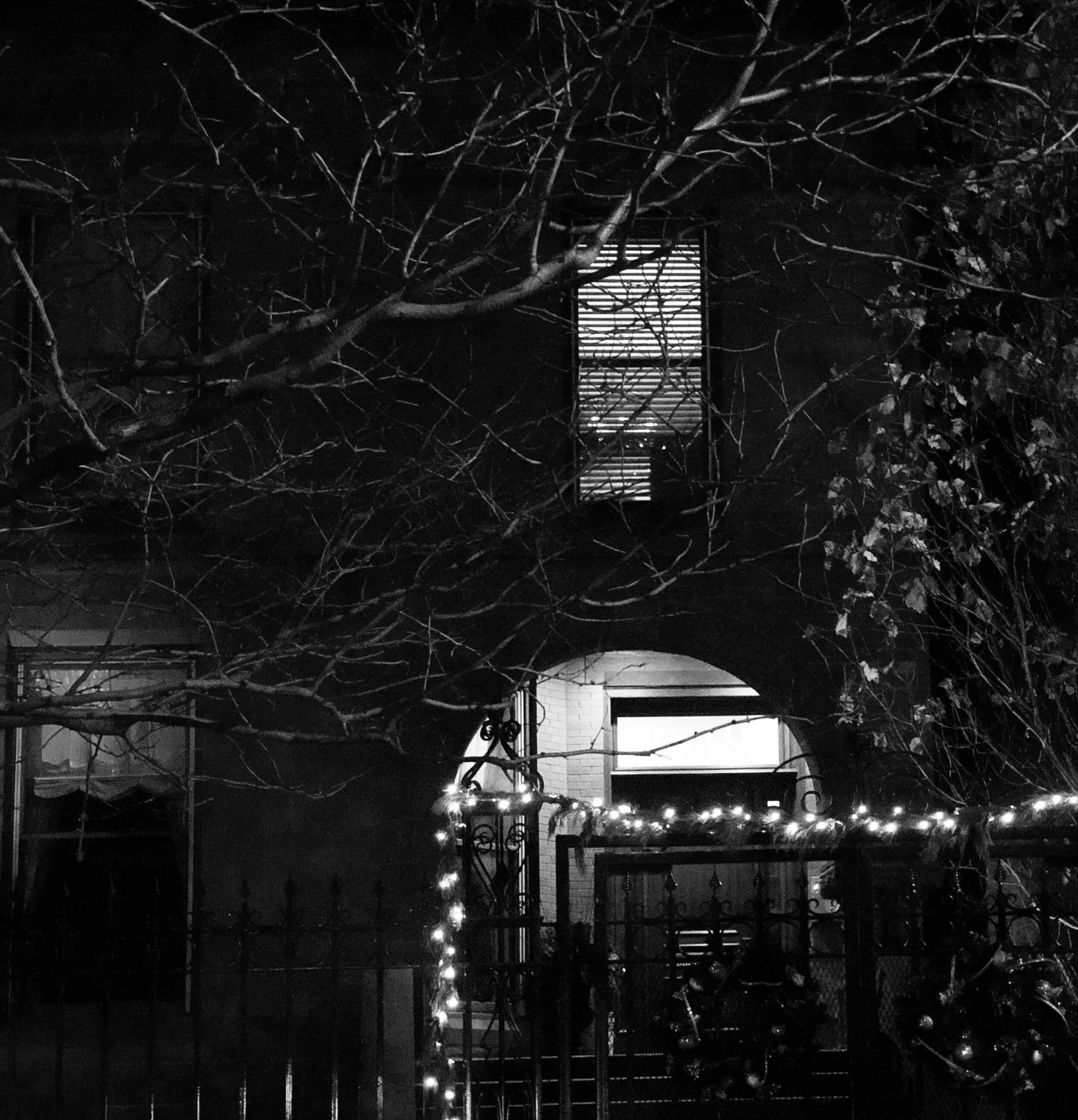

The downpour slams against windshield like a tsunami, and Maury kicks at the gas hard enough to make water spur up from the tires, throwing the car into neutral as we dip down a hill. He switches back to drive and swerves us into a vacant parking lot, and I can make out a playground distorted by the night rain. He lets the engine run. He lets the rain punch down on us.

“Bright Eyes or Bob Dylan?” He scrolls through his phone with a slender finger, screen glaring in the dark. He looks naked without his jacket, tee and jeans combo looking incomplete, a bare arm thrown over the console. He’s not tan anymore, he hasn’t been since summer, two months ago.

“Doesn’t matter. Neither can sing.” I sniff and check my reflection in the rearview.

Maury clicks his tongue. “Eloise, you’re without taste.”

I point the air vent toward him as Bob Dylan’s rattling croon starts up. “And you’re without a sense of temperature.”

“That’s true, actually.” He shrugs and drops his phone into the coffee stained cup holder, at peace with the dried splotches.

Ever since I’d waited on him last month at the diner, this had become our Saturday cycle: bowling, a drive, coffee, and then we’d part ways. The storm threw us an offbeat, Maury claiming he couldn’t possibly drive in this weather, amping the car to sixty in a thirty-five. I start to slip Maury’s jacket off my shoulders when he shuts off the heat.

“It’ll be freezing soon.” He catches me in the crosshair of his stare, dark hair curling against his peanut butter skin. His lack of a hood unnerves me; seeing his full expressions falls unto uncanny valley—like a store mannequin has just blown me a kiss. He is scraps of emotions learned from people he never sees twice, but you would think he’d know how to smile by now. Maury switches the AC on. The jacket stays on my shoulders.

We stay at the park until the rain stops drowning Maury’s snot-green Chevy, Dylan on shuffle while Maury mouths lyrics. I try comb through my rain-soaked hair before it can make my blouse damp, but the rose fabric clings to my shoulders anyway. We get gas station coffee and donuts before he drops me off at my apartment. The expired icing is still stuck to the roof of my mouth when we arrive, and I almost wish I had Maury’s crappy black coffee to scald it off. We say our goodbyes, and Maury insists I keep his jacket. I tear it off the second his car is out of sight.

***

Over the weekend, I begin to live in Maury’s jacket, despite the urge to burn it. I wear it to the dinner over my uniform. I wear it when I chat with the busboy during my break, his overgrown buzz cut matted to his forehead from sweat and humidity. I wear it so much it garners comments from my roommate, Jamie, asking if it belongs to a “secret someone.” I tell her yes, except not how she thinks, and she wouldn’t want to know whom in the first place. Her voice drops from girlish to motherly, and she comments on my pallor. I say I’ve been forgetting to eat due to double shifts; I escape her and say that I’m going to the library to study. I don’t go back when I forget my wallet. Jamie has work in an hour; I only have to avoid her until then.

***

In truth, I worry.

Sunday I wake up to find myself paper white, but brush it off as needing more sun. It’s fall—everyone is losing any semblance of a tan. Monday finds me thinner, and I actually rejoice until my clothes begin to billow in places I once complained gave me muffin top. I consider going to the ER. When Wednesday hits and I see myself without any new changes, I take it at the universe letting me off the hook and forget the mess between work and school. I zip up Maury’s jacket and let the too-big sleeves shield my hands from the stinging cold, library books jabbing my ribs.

***

I’m flipping through a textbook when it happens.

The library is a ghost town, the squeak of my sneakers pin balling off the walls and tacky skylight. Beads of black ooze from my finger onto the page, slow at first, then in a steady drip of what looks like murky in water. I rub my thumb against it; I smear black down my palm. Fat little drops splatter onto the page of my anatomy book. A papercut.

My hand shakes, so I jam it into the pocket of Maury’s jacket, snatching up my books, wondering if anyone saw. A balding old lady stares blankly at the pages of a crinkled paperback. The clerk has her nose in some trashy tabloid, and for once I’m relieved by the sight. I force myself to pass both in a collected manner, sprinting the moment my shoes smack the crooked sidewalk.

***

The inky liquid is dry when I get to the apartment. The cut is gone, and I wash my hands questioning whether it happened at all, but the stains in my textbook scream at me that this is all too real. I blink at my reflection. I get an idea.

The knives in the kitchen are far from dull. I cycle this through my mind as I align the tip of a serrated blade with my mid-thigh, steady, steady, steady.I hold onto the mantra when I push down the edge, eyes cemented shut. When I peek, there’s black on my leg. No pain.

I poke at the ghostly skin around the wound, my heart stuttering at the lack of a sting. Or, I hoped it could still stutter. The knife shakes as I drive it deeper, begging a nerve to make me relent. I cut until bone stops me.

The flesh inside my leg is a sickly gray, shades of red bleached from the meat and replaced by the horrible, dirty blackness that’s making a puddle on the floor.

I shudder and gasp when the flesh starts to move, let the knife clatter to the tile. It’s like watching a time-lapse of a plant grow, sinews threading themselves together and stitching the gash shut without scarring.

I call Maury and leave him a voicemail, screaming at him to get his ass over here before Jamie comes home. It’s just past ten when I let him in, and I shove him against the wall so hard the picture frames rattle.

“What did you do to me?” I snap at his throat.

His eyes flit around the apartment. “Where’s my jacket?”

“Screw your jacket!” I pull the collar of his shirt close enough that I sense panic and Chinese food on his breath. “What did you do?” I force him to meet my scowl.

Maury spots his jacket hung on a kitchen chair and wretches loose, retrieving it with far too much grace. He drapes it around my shoulders and tells me sit down. I drop beside the kitchen island while he sits in the black-stained chair.

Maury explains that when he was ‘inducted’, it was World War II, and he hadn’t had a choice either.

“You meet someone and you just know. That’s what the last Death told me.”

He announces that once I’m done changing—once I stop leaking black and the need to breathe subsides—he’ll crumble to dust and I will be fully fledged as Death.

“Reapers typically live a century or two, then they pass it on to someone else.”

I ask, “There’s more of us?”

“Yes,” he sighs, “but never at the same time. You and I, we’re between chapters. You’re not yet born, and I’m dying.”

“Bullshit.” I throw his jacket at his face. “ Take it back. Death dying? Take it back!”

He clasps my hand and answers that he can’t, leads me out of the apartment to his Chevy while petting my sand colored hair. We get coffee, and its dishwater taste is the only thing normal about us sitting in his car at the park. Everything is all out of order.

“There are things you should know.” His eyes follow the drizzle down the windshield, “There are simple rules.”

-

Anyone I kiss will die. This is The Kiss of Death. This is how I will help people cross over. “We don’t guide souls,” he drums his fingers on the dash, “we just give them tickets to get where they’re going.”

-

I am omnipresent, and time will be strange for a while as I become used to being unrestricted by time. This is how I will be able to ‘ferry’ multiple souls simultaneously.

-

Anyone I allow to try on his jacket–now mine–will henceforth be ‘inducted’ as I am, and I will cease to exist after four days. I am otherwise deathless.

“Four for the horsemen,” he jokes, “and you can change the jacket at will, too. Forever fashionable. That’s a perk.” Maury lets me finish his coffee. It won’t help my exhaustion, but I pitch it back anyway. We lapse into silence and the steel colored sky hovers over us, lightening cracking the air. Maury hushes me each time I try to talk, saying he wants to be human for his last moments, saying I’ll ‘know’ all answers when the time comes. He hums along to the music, and when the clock glows 11:59pm, he tells me to get out of the car and come round to the driver’s side. Slow. His clothes are in a heap on the leather when I open the door. I toss them in the backseat and put the car in drive, glad no one can hear my sobs over the thunder.

***

I keep working at the diner.

Like Maury said, when the time comes, I know.

It’s like a bell: a soft ringing in my ears, and I close my eyes and I’m where I need to be with who I need to take, and once it’s done I’m back where I first was without a second skipped.

I’ve yet to change Maury’s jacket. It’s my last trace of him, sans his ugly green Chevy.

Jamie comes home from Christmas at her parents with a new jacket, one with a leather body and cotton hood, one size too small so it’ll hug her curves—she hates the oversized look, says it swallows her figure. She models the jacket for me, exclaiming, “We’re twinsies!”

She invites me out for drinks so I strip off the diner stench with a shower, and shake the dust off my black dress. The snow’s solid enough to stick to the ground; Jamie passes me Maury’s jacket on the way to the car. I hang it over my arm, Jamie too excited to notice I don’t shiver. She slings on her jacket, then stops halfway down the stairs with a pinched expression. She turns to me.

From three steps above, I look down at her and ask, “What’s wrong?”

Jamie flaps her arms. The jacket sleeves dangle far past her pink nails.

____________________________________________________

Gabriela Everett is a creative writing undergraduate at Columbia College Chicago and presently lives in the South Loop. Everett’s previous publications include prose and poetry in Santa Fe University of Art and Design’s lit mag, Glyph.