Please visit Allium, A Journal of Poetry & Prose for the complete print and online issues of Hair Trigger.

Dulcey Lima is a nature photographer whose work has appeared in multiple juried exhibitions. Prior to pursuing photography, she worked as an Occupational Therapist and Orthotist for people with orthopedic and neurological impairments. Her intent is to capture the essence of the living world so that viewers can delight in and gain insight into the constancy and beauty of nature.

Instagram: dulceylima

Zenfolio: dulceylima.zenfolio.com

Christine Foley a graduate of University of Illinois, Circle Campus. A retired high school special educator now living in the Chicago suburbs. She currently works as a freelance photographer, and has received honors in numerous exhibitions and in CACCA (Chicago Area Camera Club Association). She is interested and grateful for the opportunity to photograph the world as she sees and feels it.

Website: https://christinefoleyphotography.zenfolio.com

Instagram: fotog247

_________________________________________________________

Visit Allium, A Journal of Poetry & Prose‘s website for the complete photography archives.

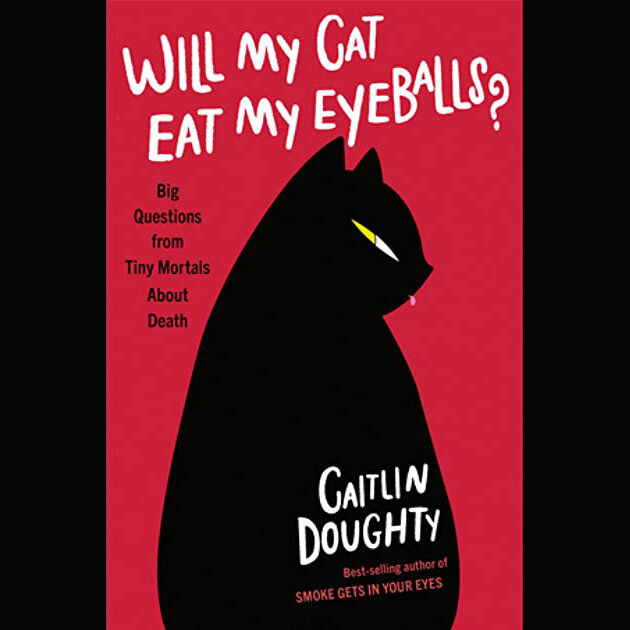

Reviewed by Sabrina Clarke

Most well known for Ask A Mortician [YouTube channel], Caitlin Doughty never strays from strange or hard questions about death. She’s a certified mortician, has worked at a crematory, attended school for embalming, traveled the world to study death customs and the culture within, and owns the funeral home Undertaking LA. She’s been a featured death expert on NPR, SXSW, TEDtalks, and other media, where she talks about the traditional practices that are enforced in the death industry and how they should change. For example, she discourages the use of traditional embalming methods with dangerous chemicals because they are harmful to morticians and the environment, offers ideas for natural burials, and would like to see changes or the creation of laws that ignore the customs of other cultures, disavowing the concept the dead body belongs to the funeral home the second someone dies. It may not seem like it, but she causes a gigantic stir in the death industry. Her idea that everyone should have a detailed death plan is something that most funeral homeowners dislike, as it’s bad for business; these steel-plated caskets don’t sell themselves, and knowledgeable masses may not buy them. It is obvious that the death culture in America in the past 100 years has changed — people fear bodies now and do not know the rights that they have when they die, or what to do when they lose a loved one. In her travels, she answered many questions from fans and audience members, but the most interesting questions come from children.

Death may be unbearably sad and can make you want to shield yourself away from such questions, let alone the answers to them. But Doughty, and many other people like her, believe that death is something that is natural, always happening; science and history and art and literature all come into play with death and death culture, and Doughty never strays from a chance to educate.

The book begins by explaining her career, introducing the reader to her sense of humor, along with the specific way she will be carrying this conversation and journey, and why she feels the need to do so. Each part of the book is dedicated to a specific question that a child asked her directly at book signings or public events. The questions themselves, like the title of the book, seem morbid and macabre, but Doughty answers them as honest questions. The tone of the book is educational and respectful. No question is a bad question in this field, and some genuinely stump her, but she tries her best to answer in an accurate and well-researched way, going down every possible path the questions can lead her. The book is humorous and genuine, answering questions ranging from “Can everybody fit in a casket? What if they’re really tall?” and “Can we give Grandma a viking burial?” While it seems dark coming from the minds of children, they are naturally inquisitive. Doughty at first was confused by how deep the questions became, but soon welcomed it and started taking notes.

Each question gets its own dedicated chapter, filled with illustrations by Dianné Ruz. The book itself is passionate and sincere with its goal to not only entertain the reader, but answer even the most morbid of questions with the respect and in-depth research that they deserve. The book is valuable to those that have questions about death, young and old.

Published by W. W. Norton & Company on September 10, 2019

ISBN: 978-0-393-65270-3

Hardcover 240 pages

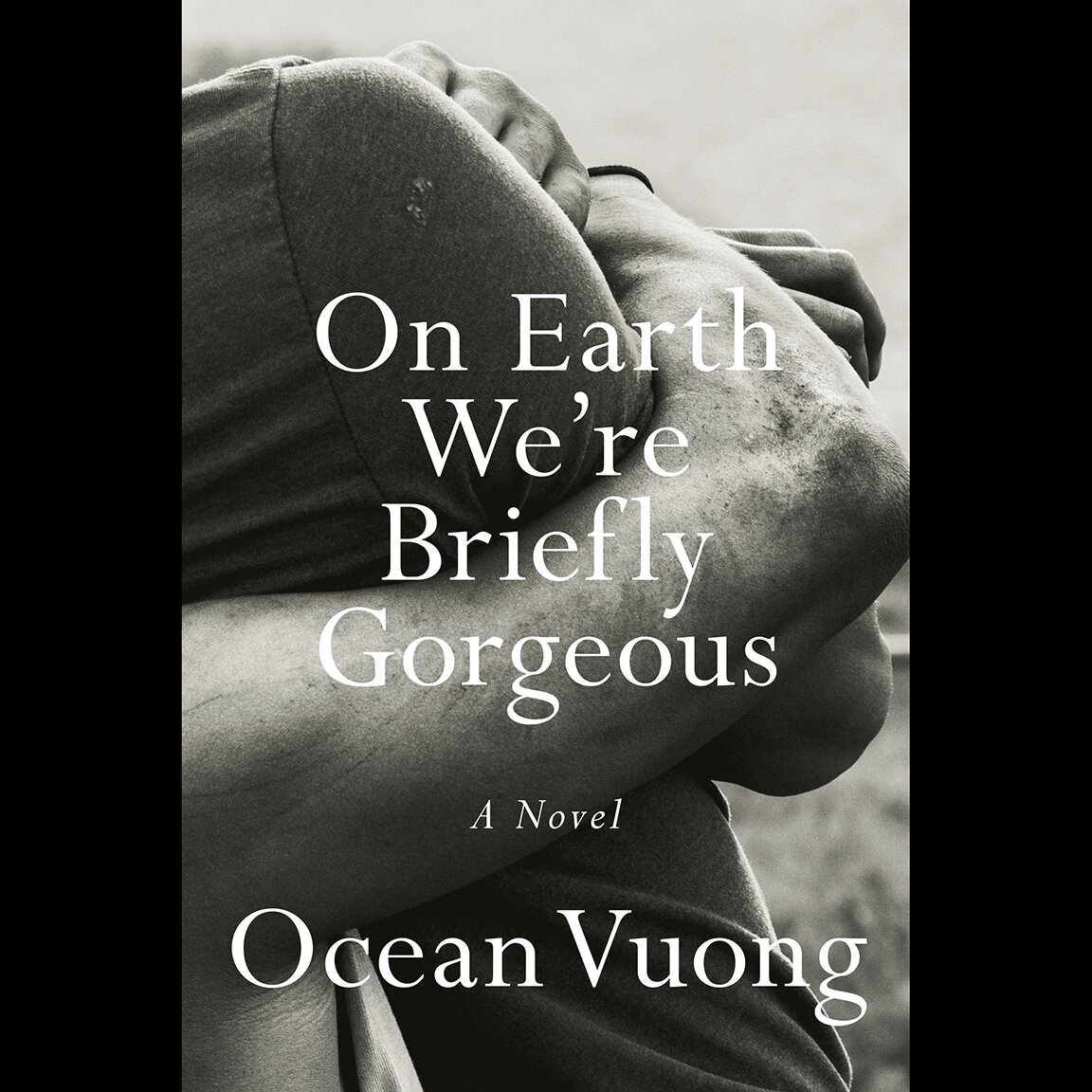

Review by Mulan Matthayasack

Poet Ocean Vuong has seen the world from both ends: Saigon and New England. He’s also seen it from different perspectives: through the eyes of a young Vietnamese boy assimilating American customs, and through the eyes of his mother. He takes these perspectives, these experiences, these family encounters, and he melds them into his first novel On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous to define not only what it means to be the son of an Asian immigrant, but also what it means to be human.

Vuong opens the book as a letter written to his mother. The prose is lyrical and reads like poetry—instance after instance, memoir after memoir that captivates, compels, resonates, and challenges. The words are sharp but smooth, the images are clear and vivid, as if he is back in Vietnam with his family. He tells of their history prior to their migration and compares their journey to monarch butterflies flying south. He describes his mother as beautiful and strong but also delicate—a rose, like her name.

Vuong expresses what he has learned he must do to “be a man.” He’s scolded by his mother for not being the bigger person even though he was bullied in school for being the smallest. He watches as she struggles with English every time they are at a store, and that triggers him to better himself, to be the family interpreter “so that others would see my face, and therefore yours.” He has to be a man because he is the only man in his family.

Vuong also addresses the problems Asian women face through the experiences of his mother and grandmother. His mother is discriminated in the States for being yellow, but back in Vietnam, was discriminated for not being yellow enough because of her white father. This is relevant to current generations, because it’s a common issue most children of interracial couples have. Likewise, his grandmother was shunned by her own mother for not sticking to tradition, for leaving an arranged marriage, because “a girl who leaves her husband is the rot of a harvest.” It may seem like another tale of an ungrateful, unhappy girl, but with Vuong’s words, readers understand it’s actually a sad reality.

On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous is a powerful book that makes us consider our relationship with our own mothers, and asks us not to take even the smallest things for granted. “Care and love,” Vuong writes, “are pronounced clearest through service.” The novel makes us recognize the concerns nearly every immigrant family has, and makes us question what we can do to resolve them. But most importantly, it makes us want to not repeat history, but also not erase it.

“Maybe then … you’ll find this book and you’ll know what happened to us. And you’ll remember me. Maybe.”

Published by Penguin Press on June 4, 2019

ISBN: 978-0-525-56202-3

242 pages

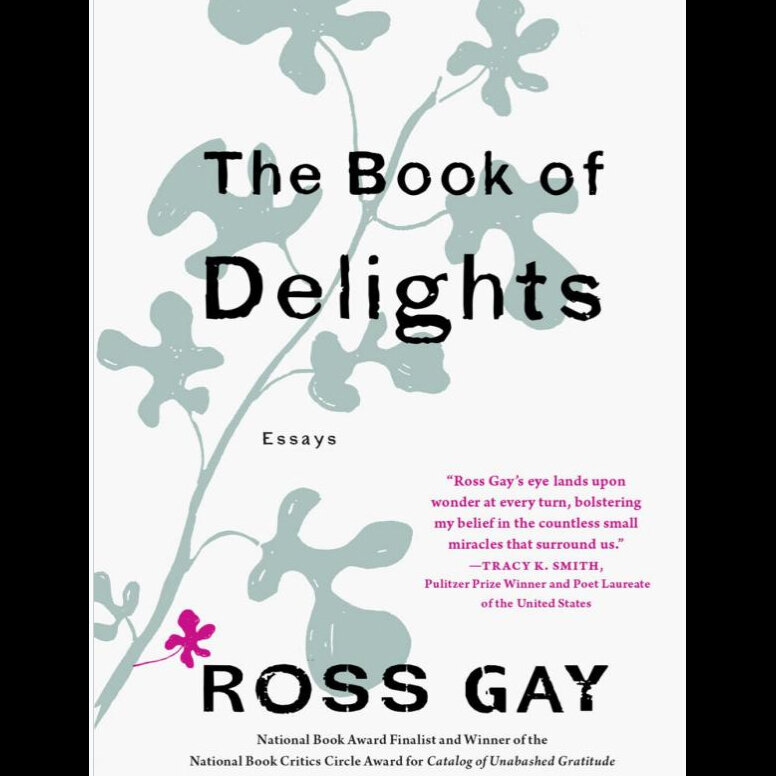

Review by Margaret Smith

Ross Gay, known for capturing the joyful experiences of life as well as the sometimes painful, debuts 102 new instances of the like in his collection of essays, which spans the time of a single year, “The Book of Delights.” Always choosing to see the delight in what can be masqueraded as sorrow, Gay spins words into short, fully realized moments that often don’t last more than two pages.

Always capturing life as it happens, Gay launches the anthology of essays with the line “It’s my forty-second birthday.” In every endeavor in this quaint collection, he takes us with him moment-to-moment—from his garden to the local woods of childhood, from the sidewalk of Trump Towers to his humble home. The book is not one streamlined plot but, rather, a multitude of them, with each entry ending by a date—timestamping it in the history of his authorship of narrative and life itself.

Gay’s precision in moments that may seem of no importance to others at first glance, zeros in on a connection to something greater. Such as in entry number nineteen, “The Irrepressible: The Gratitudes,” in which an amaranth plant is growing in the crack in the concrete, which leads his eye to a chain link fence, to a bumble bee, and to further free association, leading him then, finally, to say, “This is why I study gratitude. Or what I mean when I say it.”

The ever-present inspirations across Gay’s work are that of joy and nature. And while these are alive and well in this book, he pivots still to memories of days past, specifically regarding family. Moments of his father come quite often even if they stay for only a moment. Images of a young Gay on the play ground or in his local woods gives context to an author who seems to have always focused on what was, or is, extrodinary in moments of comfort, of confusion, of curiosity.

Chosing to ground his reader’s in the real before contemplating the theoretical or even imaginative, Gay uses the easily recognizable making nothing, not even the most complex of thought processes, inccessible to his readers. Even the unfamiliar to the author, perhaps a wave directed at him from a stranger, becomes our shared familiarity with him soon after.

But as is life—and Gay is sure to remind us of this—not all that begins in joy can end in such, or at very least, cannot always be continuosly sustained. In entry fourteen, “‘Joy Is Such a Human Madness,’” pages detailing a fall bike ride to a bakery become soworrful when, moments later, Gay writes, “Not to mention the existential sorrow we all might be afflicted with, which is that we, and what we love, will soon be annihilated.” But rarely ever to leave on a sour note, he finishes, “What if we joined our sorrows, I’m saying. I’m saying: What if that is the joy?”

The way the book is woven to leave at the threshold worries and doubts brings the reader to a sense of fulfillment; this fulfillment comes to fruition again as he closes with how he began—on his birthday, on the anniversary of a year well spent. He leaves his audience here, on this day, to go onward and bear a curiosity that leads us through the ruts of despair and into the fields of enlightened thoughts.

Published by Algonquin Books on February 12, 2019

ISBN: 9781616207922

288 pages (Hardcover)

The David Friedman Award offers a cash prize to the best story or essay published in Hair Trigger each year. Our thanks go to David Friedman’s family, who established this fund in fall 2002 as a memorial to their son, a talented writer and painter, as well as an alumnus of Columbia College Chicago and a great friend to the English & Creative Writing Department—Fiction Program’s students and faculty.

Congratulations to Nia Tipton for her story, “Bones of Before,” the 2021 winner of the David Friedman Award.

Aurora Hattendorf

Our Little Secret, part II

Asher Witkin

Your Fault

Tori Barney

Non Clairevoyant

Natalie Benson-Greer

We Can’t Drown Like Them

Danielle Hirschhorn

Haunted

Rebecca Khera

Foreign Cigarettes

Alexis Berry

It’s Not Weed

Katie Lynn Johnston

The Li’l Fingers

Zoe Elerby

The Spring Witch

Emma Dailey Mitchell

Barnabe Brenton Bishop the Third, the Northerner

Trevor Templeton

Magna Mater

Anthony Koranda

Banana Split

Nia Tipton

Bones of Before (David Friedman Award Recipient)

Jerakah Greene

The Binder

“So, where’s this guy live?” I asked, taking a long drink from my lemonade. “Your twin. Do you know if we could take a bus?”

“I’ll tell you when you play the—please,” Bonnie pleaded. She slapped the table, but it made no sound. She gestured to the jukebox. “Puck, come on‘Strawberry Fields Forever’! It’s a Beatles song.”

Bonnie had told me about a twenty-four-hour diner that had been around since she was alive. According to her, this was a popular spot for students on the weekends. Fortunately for us, it happened to be very late on a weekday, and we had the place to ourselves. The interior tried to mimic the ’50s with red booths and neon signs. In one corner sat a jukebox, brightly colored with pulsating lights.

“This is crazy,” I wheezed. I felt like a carbonated drink that had been shaken and then cracked open. “I’m having a midnight dinner with a dead person.”

“No, no,” Bonnie said, waggling her finger. “No, you’re having dinner. The dead person is begging for good tunes.”

“Good tunes my ass.”

“You don’t know real music.”

I laughed aloud, and then it slipped out before I could stop it. “You sound like my mom.”

As soon as it left my mouth, I regretted it. I stared down at my plate of french fries and let my vision blur.

“I’m sorry,” Bonnie said.

I looked up, delayed. “What?”

“For your loss.”

I straightened my back and the booth squelched under me. “Wh—how?”

She squinted her almond eyes. “I’m dead. I know a lot about the subject. I can tell you recently lost someone. Was it your mom?”

I crammed a handful of fries into my mouth to prevent words from coming out.

“Life’s too short,” she continued. “It’s cruel that we’re brought here just to be taken out again. I wonder why humans spend so much time settling for shit that doesn’t make them feel alive. The living, although I used to be one of them, confuse me.”

Inspired and feeling reckless, I pulled out my phone and held it to my ear.

Chris didn’t answer, but an automated voice guided me to his voicemail.

“We’re breaking up. Yeah, fuck it. Some things are only better in theory.” I crammed a french fry into my mouth and held the phone away. “Goodbye, my past lover.”

I ended the call and dropped my phone theatrically onto the table. Bonnie nodded, although visibly confused. Blood was surging through my veins, throbbing beneath my skin—and I should act like it, dammit!

I folded a quick origami rabbit then pushed myself up from my seat, shoving it into my coat pocket. I buzzed and vibrated from the very core of my being. Who knew talking to someone so dead could make me feel so alive? Was I being outrageous, or was this not outrageous enough?

Grief dragged me from the booth, but thrill made me fish a few quarters from my coat’s pocket. I held my hand out to Bonnie and asked, “You ready to go finish this unfinished business?”

She brightened. “Yeah?”

“Yeahfuck it. Life’s long,” I supplied. “But it seems that death is even longer.”

I strode to the jukebox and played “Strawberry Fields Forever” for Bonnie. As it queued up, I realized it was what she had been singing at the back of the classroomand one of the songs my mom would always skip on her Beatles CDs. I can remember that the times she let it play, she’d sulk to the couch and curl up. Her eyes would turn to glass and she would chew on her fingernails. I never understood why she kept the CD if that one song hurt her so dearly.

“Dance with me!” Bonnie cried, grabbing ahold of my hands and pulling me atop the booth’s table. Bonnie leaping atop the table didn’t affect it, but when I sprung up, it rattled and shook. The legs that supported it rocked as I threw my weight around; jumping and spinning and slamming my feet and laughing with the giddy spirit of the night. I felt guided by something greater than me. Movement never came so easily as it did on the tabletop with Bonnie. I felt I could never be still again.

We were lying on my uncle’s rooftop, staring up at the night sky and shivering. Bonnie told me that the song we danced to made her feel something she couldn’t explain. It had been her “special thing.”

“Where do we go?” I asked, folding my mitted hands across my coat’s stomach. “When we die. What happens?”

She told me about how when she was alive, she’d play that song when she felt like crying. Something about it, shesaid, would pull her from her dreariness and propel her into something else.

“You know, I’m not really sure,” Bonnie admitted. “I don’t think we’ve figured it out yet. I don’t know if the living can ever truly know what becomes of the dead.”

What it propelled her into, she couldn’t be sure. Only that it made her glow.

“You want to be free, but you don’t know where you’ll go?”

“I think we go back to where we began,” she whispered. She turned her face to me. “Wherever we come from, I think we go back there again.”

I didn’t tell her the thing that made me feel alive was watching animal documentaries. I didn’t tell her that I watched them in hope that they’d sink into my subconscious and become my dreams.

“Do we all go there?” I asked. I couldn’t take my eyes from hers. This was fragile, volatile, crucial.

In my dreams, I could be anyone. Anything. Opportunity was endless. That was what made me feel something.

“We do,” she decided.

I rolled my head back to face the stars. It was hard to gauge their distance in reference to anything I knew—the width of the largest ocean, the deepest craters—nothing could compare and make sense of our distance from the stars. If what Bonnie believed was true, did that mean that the living were all once stars? Did we die to be born again?

I told Bonnie that my mom killed herself. I told her that I woke up one morning to an empty apartment and a note that said, “I’m sorry.” I confessed how I didn’t understand the puzzle of my mother⎯that she always had a few pieces missing that I wasn’t allowed to put into place. The reason she decided to leave so abruptly and with no real explanationthat was the final piece I couldn’t find. I tried to explain that they found her in the remains of her own car after driving straight into a tree, but I couldn’t get it out past my hitching breaths. I didn’t cry, but I shook like I had never known warmth. I said I felt that I would feel terrible for an eternity.

Bonnie said that sometimes an eternity is however long you need it to be.

I looked at her in the blue moonlight and thought to myself that I didn’t want her to go. We had just met, but I felt I knew her for a personal eternity. I began to shiver from a mixture of relived trauma and the frigid winter, and we both felt the call of her twin brother’s house waiting for us.

I gathered myself up and made my way to the corner of the roof, sliding on my bottom to not lose balance. Before I leapt back through the window, I turned to Bonnie and decided that she made me feel the way that my animal dreams do.

When we had been on the road for a while, Bonnie said, “When it’s all finished, you know, I’ll send you a sign. To let you know that wherever I am, it’s great.”

It didn’t take us long to find the address of Thomas Rutherford, who lived two hours north. I slid the car keys from the bowl beside the front door and figured out the gears with no problem.

The interior clock glowed sometime after two in the morning. I couldn’t stop my mouth from stretching into a yawn. Strangely, at that time, I realized that I was driving for the first time since my mother died. Something in my stomach sizzled.

“Do you believe in soul mates?” Bonnie asked some time later.

“I never thought about it,” I said. “Do you?”

“I do,” she admitted.

Finally, after a long but stirred silence, we pulled up to the right address. Sitting at the curb in front of a stranger’s home, I felt nauseated. A glance at the clock told me it was close to 4:30 in the morning. What the hell is it with the spontaneous happenings of the nighttime?

“You all right?” she asked me.

“I don’t know what to say,” I said.

“‘Hello’ is a good place to start.”

The front door pushed open after one knock. Thomas, it seemed, lived in a neighborhood where they didn’t worry about intruders. There were no lights, but I could see the shadows of a well-decorated home.

I stepped into his house, my limbs quivering with adrenaline. I was in a stranger’s home. Everything was so quiet that I could hear ringing in my ears usually heard only before falling asleep at night. I took a step forward, the wooden floor whining under my weight. I winced at the sound, worried it might’ve been too loud. I waited a few beats, counting to five in my head, before I took another step.

I was reaching for a light switch when I heard the shucking of a shotgun. A man, wearing a gray bathrobe over pajamas, strode out from behind the kitchen’s archway.

“What . . . the fuck . . . are you doing in my house?”

I threw my arms up and he thrust the nose of his weapon under my chin. My heart throbbed hard and slow, pulsating stars into my vision. I swallowed and my ears popped.

I tried to speak, but only a wheeze squeezed out. My eyes filled with tears as Thomas Rutherford prodded the soft pocket under my jaw.

“That’s right. . . .” he muttered, shifting his feet so he could sway to the right. “That’s rightstay right there. You bet your ass I’m calling the police.”

I swallowed, snapping my eyes to him. A hot tear spilt over without having to blink. I felt something wet under my nose.

“Thom⎯Thom-ato. . . .”

There was no way to articulate the way he looked at me then. He’d been hunched behind his shotgun, curled over it and hoisting it upward. But the muscles in his face relaxed. The nose of his gun lowered and his hands, gripped around the fore-end, slackened.

“Who the hell are you?” he grumbled. I kept my eyes fastened on the barrel of the gun as it lowered until it came to a rest beside his foot. Finally, I exhaled.

“Bonnie sent me.”

He ran a veined hand through his peppered gray hair. “Bonnie sent you?”

I nodded vigorously. “Yes.”

“What is this?” he demanded.

“Sheyou need to forgive yourself,” I said. I cleared my throat. “She said you blame yourself for what happened. But she forgave you a long time ago.”

Thomas gave me a look that made me sincerely believe that my greatest dream had come true: I was an animal, standing in his kitchen, talking to him.

“I’m a junior at Credence,” I blurted. “Today was mymy first day.”

As far as Thomas was concerned, I was still an animal, standing in his kitchen, talking to him.

“She made me play ‘Strawberry Fields Forever’ on a jukebox,” I wheezed, trying to offer a smile. I was sure I looked like I had a gun pointed to my head. Oh, wait.

“Okay,” he said, his voice softened. “Okay. . . .”

“I’m Puck,” I said. “Puck Evans. Could you . . . could you put your gun away, sir, please?”

“Hold on a second.” He stood up straight and his eyes swept me. Fear swelled in me, building every moment he stood rigid. Then, he chuckled airily.

“You’re not Laurie Evans’ daughter, are you?”

Everything screeched to a halt. All the business with Bonnie, my night of spontaneous fun, even my heart rate. As soon as I saw recognition in Bonnie’s twin brother’s face at my mother’s name, everything stopped.

I let my arms fall to my sides.

“Wait,” I said. “What?”

“She never told you about any of it?” Thomas sighed, rubbing his forehead with a hand. “Jesus H. Christ. I cannot believe you’re here right now. What was it you said about Bonnie and forgiving?”

I was bewildered. I laughed ridiculously, nerves fizzing over.

“Um . . . how did you know my mother?”

“We dated all through high school. We broke things off after Bon passed, it was…the guilt she had about it . . . but . . . God, see, I knew you looked familiar.”

“I’m here to tell you to forgive yourself for what happened,” I pressed on. “That’s why I’m here.”

“I have forgiven myself,” Thomas breathed. He leaned against his own counter. “It was Laurie who never got over it.”

I palmed the origami rabbit in my coat pocket.

“I called to her when I made it halfway up,” he said. “She ran to the fire escape and shoved the door open. She was trying to be a good girlfriend, she never. . . .” He exhaled. “She never got over it. I took the blame for her, told everybody that I’d opened the door. Even after we broke up, I still stuck to the story.”

The final piece of the puzzle clicked horribly into place.

“How is Laurie, by the way? If you don’t mind me asking.”

I kept driving north. I couldn’t go back. I had twisted the radio on to prevent any need to speak. “Dancing Queen” by ABBA was taunting me in full stereo. Bonnie hadn’t said a word for the entire duration we had been driving in the opposite direction of home. When she did finally speak, it was a whisper.

“Puck, I am . . . so sorry.”

“Sorry?” I burst out, hysterical. I twisted the radio off. “Why would you be sorry? My mom’s the one who should be sorry. She’s the one who killed you, isn’t she?”

“Puck”

“No, Bonnie,” I cried. “We drove to see your brother, he shoved a gun in my face, and then told me that my mother was a murderer. And that the guilt she’d been hiding all this time killed her? I feel like my whole life was a lie!”

Bonnie sat in the quiet, letting the radio get some time in, before she murmured, “I don’t like that you’re upset. It was an accident. I forgive her.”

“And you know what I don’t like, Bonnie?” I yelled, my voice breaking and my throat burning. “I don’t like that I drove all the way out to this guy’s house for nothing. You’re still here. Unfinished business my fucking ass. The world’s unfair and we’re all a part of a cosmic joke!”

The engine roared as I pushed my foot down.

“Puck, stop,” Bonnie pleaded. She gripped my hand. “I don’t want you to get hurt.”

“What’s any of it matter?” I sobbed. “What the fuck difference would it make? You’re stuck here until you get your unfinished business resolved, and I’m stuck here until I can stop fucking suffering.”

A pair of headlights rose over the hill and shone into my eyes like flashlights. I squinted into the light and flipped down the sun visor, hands shaking.

“I care about you, Puck. Listen to me.”

At the same time, we whirled to face each other.

“You’re dead!”

“I love you!”

After a few beats of silence, I slackened against the car seat. Our eyes locked together in an eternity. Every bit of anger and pain I felt melted down through my feet and every rush of sound faded to the quiet. I sort of chuckled, “Wait, what?”

Then, as her delicate face crinkled with a smile, she whispered, “That was it.”

Thirty years was long enough for someone who never let themself love others.

I was halfway through my exhale when the incoming truck smashed into our car, glass exploding from every angle. Tires squealed against asphalt as metal ground against metal. Gravity rushed as the car flipped. Glass shards glittered in the air like they’d been lifted by magic as I slammed around in my seat, helpless.

Finally, after the car landed hard on the drivers’ side, everything was still.

Beside me, Bonnie was holding onto me. I could see the strobes of headlights through her. One moment, I could feel her form clinging onto me, but then I couldn’t. She was like smokeher form wisping before me. I squinted in the bright light. I couldn’t hear what she said, or say anything in return, but another second later and she was gone.

ONE YEAR LATER

Thomas Rutherford left a voicemail earlier in the morning.

Hey, Puck. It’s Tom. Charlie and I are going to the movies later, and she needs to know if you could watch Allen tonight? We’re thinking of catching the 7:30. If Chris wanted to tag along to keep you company, he’s more than welcome. All right, well. Let me know. Talk soon.

“Sue said it’d be good for me,” I told Chris. “Babies are cute. New life—offspring. You know.”

“You pay this woman fifty dollars every week to tell you to hold babies?” he laughed. “I’d start looking for a new therapist if I were you.”

After the accident last year, when a doctor came in to wrap my arm in soft bandage, I turned to him in delirium and told him that my mom killed herself. He asked if I needed to talk to someone or if I wanted to stay a bit longer. Although I hesitated, I said yes.

After my physical wounds were mended and bound back together, I spent a couple of weeks where they would tend to my emotional wounds. They could not be stitched, but they found a way to begin closing. They weren’t sealed, but at least they weren’t gaping anymore.

“Do you think you and Liam will ever adopt?” I asked Chris, clicking my seatbelt. After our breakup, I tried to reconnect with him platonically. This proved to be the way we should have been with each other since the beginning. Not only because we weren’t meant to mold each other to our own liking, but because he confessed through a tearful phone call that he was gay.

“Guess we’ll see how I do with this kid, huh?”

The drive to Thomas’s home was one I grew regular with. He and his wife, Charlie, had Allen in the spring of the previous year. I’d left my phone on the floor of his kitchen, not noticing I must’ve dropped it when he shoved the shotgun at me. He returned it to me and said that if I ever wanted someone to talk to, I could call him. As weird as that sounded, I took him up on the offer once I was finally released from my inpatient treatment. On the regular, I visited his house and poured cups of tea and spent more time watching the curling steam than looking at him. He looked like Bonnie. They had the same button nose and the same dark hair, although his was peppered with gray and his skin hung off his face in a way that was still youthful, but that betrayed hints of age. His face creased at the edges of his eyes where Bonnie’s had been preserved. It hurt, but it hurt more to be without someone who felt like her at all.

On the day Thomas left the voicemail, it marked the one-year anniversary of my night with Bonnie. I had been both dreading and anticipating the day for months since I knew it would stir all kinds of pain in me. I often replayed the slowed seconds we took just to exist in the same space—with her unfinished business ending with a final confession of love. I had forgotten about our little secret from the pool, how she had kept her distance in life to keep her heart.

I thought of her every day. Not a week passed without me yearning for the way I felt on that rooftop with her, trying my best to recreate it with others. But it was never the same. Nobody’s presence felt like Bonnie’s had.

My origami napkin rabbit sat up on my dashboard. I couldn’t help but feel that I was waiting for her sign. That night, on the way to Thomas’s with her, she had said she was going to send me a sign. But after she had gone, that was it. I wondered for a long while if I had dreamed the whole thing.

“Good God,” Chris groaned. “You like sitting in this silence? Come on.”

He reached forward and twisted the radio on. He surfed through the static for a few beats, trying to zone into a station, before coming to rest on modern pop.

When we rolled into Thomas’s block, the radio crackled. Static whooshed over the radio, making Chris grunt in frustration. He gave it a few whacks.

A new song came in, and he relaxed back in his seat.

I knew it as soon as it began. It was “Strawberry Fields Forever” by the Beatles.

Everything around me turned golden and warm. It could have been summer for all I knew in that moment. Chris looked at the radio strangely, but he didn’t say anything.

I was in my underwear at the edge of the pool. I was plunging beneath the surface and she was pushing her palm against my chest. We were dancing on the table and running through the parking lot. I was on my roof, turning my face to meet hers. And then she was looking at me in my passenger seat, eyes alive and bright in her true, final moment on this Earth. That was it.

“Puck?” Chris said. I’d parked at the curb of Thomas’s.

I looked at him.

“Is everything okay?”

On the treebank of Thomas Rutherford’s home, a mourning dove curled her toes around a sprig of a branch. Her chest puffed as she nestled comfortably, dew drops glittering from her plumage. Following my exhale, I recalled the shimmering glass of the crash after Bonnie said she loved me. Sometimes, an eternity can be however long you need it to be.

“I think it will be,” I decided. “Not now. But one day I think it will be.”

I didn’t know she was dead the first time I saw her. But the last time I saw her, I knew that she was alive. Even if just for a moment, in that swirling smoke, she was everything at once. I never believed in fate before I met her. And after all, that night’ll always remain our little secret.

Aurora Hattendorf grew up in the small town of Elgin, Illinois before attending Columbia. They’ve never been published.

I hate this apartment. I hate the floor, and the walls, and the ceiling. I hate the drunken shouting two floors up, the moaning bedsprings, the neon signs advertising vacancy. No wonder. No one in their right mind would want to live here. The lights don’t work all that well either, but to be honest, I’m kind of grateful. A single bulb by the side of the bed illuminates just a sliver of floor, and still I can see mounds of bent and broken bottle caps, towers of ash and several black stains in the carpet. The scary part is that I cannot remember for which of these I am responsible.

I remind myself that this is not a permanent solution. It’s not all bad either. The people across the hall are smuggling a dog, a chocolate lab named Annie, who’s absolutely adorable. It’s warmer here than anywhere I’ve been before. It’s just hard sometimes, you know? Like, they build up college to be this incredible thing, like all you’re gonna do is stand in front of manicured lawns, smiling angelically, surrounded by a group of improbably diverse friends. I mean, we live in Arkansas. How stupid do they think we are?

Again, I tell myself that I’m going to find a job, that I’m going to get out of this place, that everything’s gonna be fine. I almost believe it too, sitting on my mattress, following the twisted cracks in the paint on the ceiling. I think that if one’s going to get hungover, it’s probably best to do it on a Saturday anyways.

I wake up some time later, the left side of my face sweaty from being pressed against the sheet. I’m still not used to the heat. My phone says it’s 4:45 p.m. It’s not late enough to try and fall asleep for the night, so I convince myself to get up and walk into the living room.

The place is essentially one large trash can. I count a total of five one-liter Mountain Dew bottles lying empty in various corners of the room. My clothes seem to have planned an elaborate escape from their regular positions on the floor of my bedroom, several have made it as far as the kitchen table. I need to call Mom. Instead, I grab a handful of trail mix and plop myself down on the couch.

I flip through soap operas and car commercials, but nothing grabs my attention. There’s a couple fighting upstairs. Someone’s blasting music down the hall, I can hear the bass pounding through the walls. The TV flashes different colors, pink and red and yellow, as I flip through channels, too fast to really see what’s playing. Suddenly, I need to get out of the apartment. Like, right now. It feels a little hard to breathe. I squeeze my eyes shut. Calm yourself down, you’re okay, just go the fuck outside. I manage a shallow, shaky gasp of a breath that only makes me more panicky. Feel your feet against the carpet. Can you feel the weight? I try, I actually do, but I’m not really in my living room anymore. One of the scary parts about it, is how fast it happens.

Some part of me knows that I’m still inside. I can feel the warmth of the sun on my back through the living room window. I can smell sweat on my skin. But I can smell other things too: tequila, and weed, and this one very specific musty smell Rebecca’s car always had. I can hear music turned up way too loud. I can feel the bass in my hands through the steering wheel.

“Eli, it’s you,” Rebecca says. There’s a lit joint in her hands. It’s dark. Through the haze of smoke I can see the green glow of the little clock on the dashboard reads 1:34 a.m.

I laugh. “Dude I’m driving.” She starts to turn to the backseat, ready to pass it on. “No, wait,” I say. “Will you hold it for me?” I laugh again, loud and drunk and fearless. And then Rebecca’s laughing too, her arm moving back toward me. Smoke twirls from the end of the joint as she glides it through the air. She puts it up to my lips and I breathe in. I can feel the damp paper on my mouth, the hot air entering my lungs, the warm hum of my whole body.

The stoplights are blinking red. There’s basically no one on the road. From the backseat, I hear Tyler say, “Oh my god. Eliot, is there an In-N-Out anywhere near here?”

Behind me, Max shouts over the music. “There totally is! Wait, Rebecca, can you see how far it is?”

She looks at me, I nod, and she takes out her phone. The music feels amazingly loud and warm and sparkling. I mouth the words, watching the thin white lines on the road blur together. Rebecca’s voice brings me back, for a moment. “It says it’s nineteen minutes.”

I’m studying the way our headlights bounce off road signs. Everything’s glowing. Far ahead, the city sprawls out between the hills, a million little lights twinkling in the distance.

“Eli, do you wanna go?” Rebecca asks.

“Uh, yeah.” My tongue feels heavy.

There’s much rejoicing in the backseat, but it’s buried under the music and several layers of mental fatigue. My arms feel really heavy now too. I shift in my seat. Occasionally a car will rush past on the other side of the barrier, making a swooshing sound. The streetlights slip by like shooting stars.

“Eli, slow down.” Rebecca’s voice is slow and soupy. The bass is still pounding. “Eliot.” It sounds like those videos on YouTube where people add effects to songs, so it’s like “‘The Night We Met,’ but You’re Under Water at a Pool Party” or whatever. I can hear the engine whirring. “Eliot! Jesus Christ Eliot!”

My whole body tenses up when we hit the median. I can feel it for weeks afterward, like none of my muscles can ever fully relax. It feels like I’m getting punched in the face in slow motion. I can’t breathe. I can’t see. For a second, I think the whole car has flipped and my face is being pressed against the floor. Am I still sitting in my seat? I reach my left arm up, trying to feel for a seatbelt and my shoulder explodes with pain. I scream, at which point it becomes clear that my face is being pressed into fabric. I can feel the rubbery thread against my tongue.

For a few beautiful moments, all I can feel is the pain in my face and my shoulder, and even though I know what just happened, it doesn’t really click yet. I hear Rebecca, her voice no longer distant, making a sort of choking sound; I feel the wheel still clenched between my fingers, and the thought balloons until it’s the only thing I think, until I can’t imagine being able to think anything else ever again: your fault, your fault.

I squeeze my eyes even harder, my mouth pulled back in a sort of grimace. My fists are balled up, pushing against my eyelids. Sweat pours down my back, my thighs slick against the fake leather of the couch. Your fault, your fault, your fault, your fault. The TV is still on, some stupid jingle bleeding into my consciousness from the edges. Your fault, your fault, your fault. My heart is beating really fast. I can still smell the tequila on my breath. Your fault, your fault, your fault, your fault.

“SHUT UP I KNOW!” I open my eyes, my scream still echoing around me in the empty living room. It’s late afternoon. A woman on TV is singing about her new electric toothbrush. I rest my head against the back of the couch, looking up at the low ceiling. “You’re okay,” I say, again out loud. “You’re a fucking idiot, but you’re okay.”

I’m still not ready to move. For a while I just sit there, waiting for my body to calm down, listening to someone fight with the trash chute down the hallway.

Eventually, I convince myself to get up. I strip off my sweat-soaked clothes, toss them onto the floor with their friends, and get in the shower. I let the hot water rush over my face, feel my feet against the smooth tiles, and for a moment, I really am okay. Standing there, making patterns in the condensation on the shower door, it feels ridiculous that I ever let myself get so overwhelmed. I make a list in my head of the chores I still need to do. How hard is it to clean my room? To apply for jobs? To call my mom?

It amazes me how quickly my mood can shift. Intellectually, I know that I’ve felt this way before, that my short bursts of self-confidence invariably collapse in on themselves the moment I’m confronted by the prospect of actually turning my plans into actions. But each time I get this way, it feels real. It feels sustainable. Each time I get this way, it feels like this time, I’ve found my way to a place of real stability.

The room is pretty hot now, steam pooling against the low ceiling. I take a deep breath, a real one, without the shake or tension. Who’s to say I’m wrong?

Asher Witkin is a singer-songwriter from Berkeley, California. While these are his first published pieces of writing, you can find his music wherever you listen to songs, or check out his website at asherwitkin.com.

You made me love winter.

You made me love watching snow softly fall past the dashboard, in a different world when everything was quiet. You held my hand because of the cold, and traced circles. “Can’t Take My Eyes Off You” shuffled on, and you would begin your terrible singing to me. You grabbed your phone and sang into it, as if performing onstage. It was really bad, so I told you to “staaaap,” but you didn’t, you just kept smiling. I laughed so hard my head fell back, and my eyes squinted real small.

When we were done, we drove back to my house to watch your favorite movies. I’d listen to you talk, drinking in your words, watching your pupils expand. The way your face lit up when talking about specific shots or scenes made my love grow not only for you, but for your interest as well. I never knew I’d obtain more passions than I already had.

It wasn’t long until I found myself using words or phrases I only ever heard from you. I also found myself laughing or smiling like an idiot whenever I caught myself in the act. We traded habits, both good and bad. You were becoming a part of me, and I let it happen.

For the first time in a while, winter was my favorite season again. I had good memories replacing the old, damaged ones. Like the time it snowed so much you made me stay in the passenger seat when arriving at my house.

“Don’t move, stay right here.” You turned off the ignition.

“What? Why?”

“Just trust me.”

I wasn’t sure what you had in mind until I saw you shuffling over to my side of the car. You opened my door and motioned your hands to lift me.

“I know how to walk,” I laughed.

“Yeah, but you’re gonna get all wet.”

“So?”

“C’mon, just let me be cute.”

I couldn’t stop staring at your cheesy smile. I thought the situation was dumb, but let you continue anyway. You picked me up bridal-style, and I wrapped my arms around you, pulling myself closer into your warmth. You smelled of cologne and gum, and I never wanted it to go away. We trudged through the snow, laughing so hard you nearly dropped me.

Moments like that helped me forget about those winter nights with my mom. The nights she’d pretend our family was still perfect. When she’d scream about how my dad was Satan himself. Or when she called the cops on my brother and me for not behaving “well enough.” Divorce makes people crazy. But time with you made me forget the mess and focus on the good given to me.

Months later, I should have noticed.

I should have noticed those three words becoming more and more distant. I should have noticed the way you talked about her¾the same way you used to talk about me. I guess I was too busy falling to pay any attention.

Once I put the pieces together, I asked. You denied. Said my jealousy was showing.

I should have known better when the excuses flooded in:

“Dinner tonight?”

“Sorry, I can’t. Sky needs me tonight, family stuff.”

“We still on for the movies?”

“Sorry, I have a lot of homework. Maybe tomorrow?”

“It’s been a while, do you want to talk tonight?”

“I would love to, but I’m actually about to go to bed.” When in reality, you were going out.

From then on, I’d overanalyze every moment, every sign. I did everything I could to save it, but in the end, I knew I wasn’t enough. Even now, I sometimes wonder if I ever was.

I figured when it ended I would have felt prepared. I mean, I knew it was coming. Instead, I felt heavy and empty all at the same time. I was drowning above the water. When you left, you took all the simple joys with you. You stole parts of me I didn’t know existed until now.

During the day I occupied myself with anything and everything. At school I actually participated, volunteered to speak, and was the leader in groups. At work I gave my everything, not allowing myself to slack off for one second. I knew that if I did, my mind would wander too far. I put all of my energy into the things I loved. I hung out with family and friends, hoping they could help fill the void.

At night, when I lay in bed, looking in the spot you used to be, I felt alone. I was trapped in my thoughts with no way to escape. The only way I got through was by accepting them and imagining a world where nothing was wrong with me.

I remember the next winter, riding in the passenger seat of my dad’s car. We were on our way to my grandparents’ house for Christmas dinner. It was one of the first moments my mind wasn’t constantly wrapped around the idea of you. The side of my head pressed against the cool glass, watching flakes fly past us. We drove along cookie-cutter houses decorated perfectly for the event.

Out of the corner of my eye, I saw a couple building a lumpy snowman in their front yard. The girl smiled so wide at the boy, you could hardly see her face. And when she wasn’t looking, I’m sure he admired the way her hair fell just below her shoulders. Or the certain way she shook when she got cold. He was in love with all her little things, and she probably always knew.

I looked back toward the road in front of me, listening to the music that flowed through my headphones. That one song you used to sing to me shuffled on, and I immediately skipped it, trying to erase you from my memory.

You made me hate winter.

Victoria Barney is a creative writing student at Columbia College Chicago. She has been an editor for Hair Trigger and is always looking for new experiences within the writing world. Additional information can be found at https://nerdfightertori.wixsite.com/mysite.