Vanishing Point

My father died in 2017 at the age of eighty-five. The death of a parent is a pivotal experience. A natural impulse is to try and put that parent’s life into some sort of recognizable context. It is a time of mourning, as well as summing up.

By the time my father died, he was a Holocaust survivor. This may sound paradoxical, because he was, in fact, that very thing: A Holocaust survivor who had hidden out the war in Belgium. Those are the plain facts. He was born in Brussels in 1931 to two Polish Jewish parents who had emigrated to Belgium the previous year.

In the late 1930s, his father—my grandfather—in a case of lethally bad timing, emigrated to New York City, intending to send for his wife, son, and daughter. The advent of the Second World War made this impossible; in 1940 Belgium was under Nazi occupation. Those are more plain facts, but these facts become plagued with ambiguity almost immediately. What was the nature of my grandfather’s relocation to the United States, just before Europe burst into flames? After the war, he did send for his son and daughter. Was it pure abandonment, as my father came to believe? Or something else? There’s no answer. My father’s wartime narrative, from the outset, becomes muddied.

As the German knot tightened, my father and his sister were among a group of Jewish children who were hidden—basically in plain sight—as pupils in a Catholic school, where they all passed as gentiles. My grandmother was caught, transported to Auschwitz, and perished.

Holocaust commemorations rely on bare facts and narratives that have a beginning, middle, and an ending. These narratives are often presented as examples of good triumphing over evil, or lessons in moral instruction. Nuance, ambiguity, and contradiction are banished. There is no room for the horrible murkiness of trauma, grief, mourning. My father’s own chronicle—the way he recounted it– did not have much in the way of a linear progression.

It was only in the last decade of his life, really, that he identified himself as a Holocaust survivor. To the best of my recollection, the word Holocaust never passed his lips during my upbringing. References, when they did come, were to “the war,” which needed no additional amplification. Belgium itself was almost a secondary factor; he had been raised in Brussels, which was absent any elaboration: Simply the name of a city, a place. Just Brussels.

My father’s account of his mother’s fate was this: She would visit him every day. One day she simply stopped coming and was never heard of again. End of story. It is a child’s tale of wishful thinking. The mother simply vanishes. She is not loaded into a cattle car to meet her death in an extermination camp. She is not beaten, starved, or gassed.

One of the greatest joys of my life was, when my daughter was little, engaging in the ritual of bedtime reading, seeing these magical books through her eyes. It was during this period when I suddenly realized I knew not a single one of my father’s favorite childhood books or tales. He was nine when the Nazi regime began. Nine is a fairly well-developed age, full of preferences and interests. I don’t know the name of any of his friends, teachers he liked or didn’t, favorite movies, songs. I have no idea if his mother read to him every night. Not a single one of his childhood books or toys is extant. There are almost no photos of him as a young person.

Scattered anecdotes, when I was growing up, did creep in. He loved Tintin and went to the movies regularly. He had the first bicycle on the block, imperiously meting out the length of time that the other children had to try it out. There were regular family trips to the beach. The beach, in fact, is the only photograph we have of my grandmother where she is posed with her two young children.

One could deduce that the beach was in Belgium, but it had no specific name or locale. It was only during that last decade of my father’s life that it occurred to me to ask where this beach was, exactly. I then learned the name was Blankenberge, where pasty-faced British vacationers also sojourned. I had not known any of this; not the name, not the composition of its visitors.

His stories from the war would sometimes make their brief, unsettling appearance, popping up and disappearing: spare and strange, in the words of Gerard Manley Hopkins. Once, while lying in bed, he had heard a man being shot and the subsequent cries of pain. During the period when he was in hiding he subsisted on leeks. These were stories related to me when I was younger. Perhaps the intervening years have diluted my own accuracy, although I tend to doubt it. Those are the sort of jolting details a kid would remember.

He also mentioned—once and only once, sans any sort of detail—some person who had a special, extrasensory ability to identify Jews by sight alone, this deadly presence who went around with the Germans. This also, in retrospect, seems like a children’s tale or rumor. It is horrifying, of course, but also, I imagine, comforting in those nightmarish circumstances: If you could stay out of this mythical person’s way, you could perhaps survive. The reality was that there was no formula whatsoever to survive.

My father came to this country as a teenager, but still maintained strong linguistic and cultural ties to Europe. I remember copies of Paris Match, for example, all during my childhood. These ties were all culled from France, not Belgium. That was to be expected. The infrastructure of the Francophone world is, obviously, not heavily tilted toward Belgium. Yet I remember nothing of Belgium penetrating our home.

A cordon sanitaire is defined as “a protective barrier (as of buffer states) against a potentially aggressive nation or a dangerous influence. . . .” He had constructed a cordon sanitaire around his past. Our house was permeated with his presence of absence.

As my father began to decline physically and mentally, he began to suffer from war-related hallucinations. The Germans were breaking into his house, for one. My visceral, utterly illogical reaction was one of relief. He really had gone through the Holocaust. His trauma was codified, identifiable. Again, this is completely illogical on my part.

It all boils down to the mother, doesn’t it? The mother makes everything bearable. When there are bullies, the mother is your recourse. The mother protects you, not just from bullies, but from all manner of bad things. In my father’s case, these particular bullies are shockingly malevolent. As it turns out, they want to do more than bully; they want to inflict great, enormous harm. And then it escalates: They actually want to kill you. The mother is powerless to stop this, to save you. She can do nothing. And then the bullies mean to inflict great harm on your mother as well. It is more than great harm: They want to kill your mother. And they do. They kill your mother.

The painter Arshile Gorky was a survivor of the Armenian genocide, a witness to his mother’s death from starvation. His extraordinarily moving The Artist and His Mother depicts the young painter side-by-side with his mother, who is looking out into the distance. I can think of nothing that illustrates my father’s experience with such tragic, wrenching accuracy.

The young boy in the painting is gazing out as well. Mother and son are juxtaposed close to each other, their sleeves almost touching. They are not looking at each other, but the figure of the mother looms large. She is so tangible, but not quite there. It is as if Gorky painted The Artist and His Mother fully cognizant of my father’s story.

Next to the mother is a boy. Just a boy. And that is all, ultimately, there is to say.

_______________________

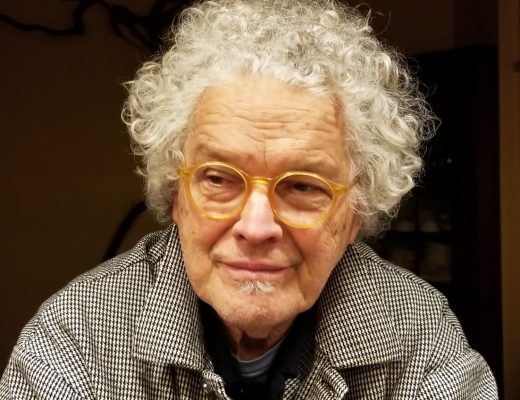

Richard Klin is a writer based in New York’s Hudson Valley and the author of (among other things) the novel Petroleum Transfer Engineer (Underground Voices). His work has been featured on Public Radio International’s Studio 360 and has appeared in the Atlantic, the Brooklyn Rail, the Forward, Akashic Books’ “Thursdaze” series, Flyover Country Review, and others. He has recently completed a new novel.