Ken Krimstein has published cartoons in the New Yorker, Punch, the Wall Street Journal, and more. He has written for New York Observer’s “New Yorker’s Diary” and has published pieces on websites including McSweeney’s Internet Tendency, Yankee Pot Roast, and Mr Beller’s Neighborhood. He is the author of Kvetch as Kvetch Can and teaches at De Paul University and the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. He lives in Evanston, Illinois.

Ken Krimstein has published cartoons in the New Yorker, Punch, the Wall Street Journal, and more. He has written for New York Observer’s “New Yorker’s Diary” and has published pieces on websites including McSweeney’s Internet Tendency, Yankee Pot Roast, and Mr Beller’s Neighborhood. He is the author of Kvetch as Kvetch Can and teaches at De Paul University and the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. He lives in Evanston, Illinois.

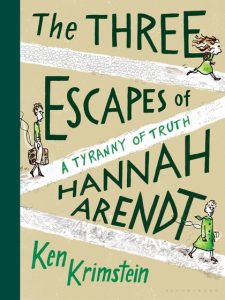

In a lively email exchange, Ken Krimstein communicated with Punctuate Managing Editor Ian Morris recently about his new book The Three Escapes of Hannah Arendt: A Tyranny of Truth, a graphic memoir of Hannah Arendt and the philosophy and history of her age.

Punctuate; Fans of your New Yorker cartoons will likely be surprised that The Three Escapes of Hannah Arendt is a graphic history of twentieth-century European philosophy. What inspired you to undertake this project?

Krimstein: In addition to loving what we in the cartooning business refer to as “gag” cartoons, single panel “jokes,” with or without words (think Charles Addams, S. Gross, George Booth), I’ve always loved longer form comics. Sure, it started with Superman and Batman when I was a kid, but I also inherited from my great uncle many comics in a series entitled Classics Illustrated. You can imagine what they were—definitely not comics about men in tights. Comics of Moby Dick to The History of World War I. I loved them all. As I got older, I discovered the wonders of R. Crumb, and of course Maus, Persepolis, and on and on. In addition, I’ve always been a huge fan of both biographies and of philosophy.

One question has always intrigued me—how does a person’s life affect their art or thinking?

Now, add Hannah Arendt to the equation. She was always on my radar. I think I first tried reading The Origins of Totalitarianism when I  was in middle school. And her later idea of “the banality of evil” seemed fresh and unexpected and important. I wanted to wrestle with it.

was in middle school. And her later idea of “the banality of evil” seemed fresh and unexpected and important. I wanted to wrestle with it.

While working on my weekly New Yorker submissions, my agent said a publisher was interested in seeing “anything,” from me, whatever I wanted to do. I thought, “Aha! I’ll do that long-form comic treatment of the enigmatic Hannah Arendt.” And when I actually opened the biographies, I found at every turn the events of her life were completely compelling. Her character and her thinking always impacted me in a powerful way— I felt like I knew her. I couldn’t not do it.

Punctuate: You describe Arendt as “arguably the greatest philosopher of the twentieth century.” Did you see it as a personal mission to call more attention to her life and her work?

Krimstein: I really believe her thinking is profound. Now, understand, I am not a licensed professional philosopher, though some of my best friends . . .

In any case, as I dug deep into her work I saw how she took ideas in Continental Philosophy— phenomenology, existentialism, the inspired mélange of thinking that poured out of her great friend Walter Benjamin—and gave them a totally unique interpretation. In the place of living “unto death,” which was fairly widespread, she saw much of life’s meaning as arising “from birth—births.” She celebrated the creative force. What’s more, she questioned the contemplative life of the philosopher, and energized, if you will, the thinking I’d read from the likes of Sartre (and even Camus), and made it all very present, action oriented. These bold turns did completely new things with thinking. So much of what she lived and thought has been understood in headlines, often headlines people don’t really understand (truth be told, I’m not sure I understand all their nuances either, but what I get is powerful). I wanted to get beyond the headlines and follow her thinking wherever it led. And it led to some very thrilling places.

So, yes, in my opinion, she needs to be read and discussed and learned. A lot.

Punctuate: Arendt was preoccupied by the possibility of a truth, “one universal answer to understanding,” and yet the book is subtitled “A Tyranny of Truth.” Can you describe how this quest evolved and how it informed her philosophical writings throughout her career?

Krimstein: In trying to tell her story and give it dramatic drive, I had to show how she evolved and how the events she lived through “grew” her thinking. As I see it, and tell it, she focused her incredible intellect and talent on the classical pursuit of understanding, even total understanding. But as she endured crisis after crisis—her father dying of syphilis when she was a precocious child, having a emotionally searing “affair” with her much older (and married) philosophy professor (Heidegger), escaping the encroaching Nazis from Germany and then from France, finally having to face the horrors of the Holocaust, her thinking led her to a virulent truth-telling, because she learned that from lies came horror. And, I surmise, from the notion of “one single all-encompassing Truth,” she came to value a myriad of “truths,” a facing of reality that cannot be avoided.

Punctuate: Did you have a preconceived notion of Martin Heidegger when you started writing the book? What did you learn about him that surprised you as you learned more about him?

Krimstein: I really didn’t know that much about him. Really. I’ve said that I approached the book as a “typical NPR listener.” So when I found out about the affair and the Nazi sympathies, not to mention his work in “Being and Time,” I learned about him in many ways for the first time. Of course, I’d heard his name. I’d heard people in the Philosophy Department speak of him as “very important.” I knew there was “controversy.” But I wasn’t sure of the details. What surprised me about him? Everything? He used to ski to class. He lived in a hut in the woods. He was a serial womanizer, and his wife endured it. His wife was even more outspokenly anti-Semitic than he was. In his early, pre-1933 days, he attracted droves of the smartest Jewish philosophers—from Levinas to Marcuse to Leo Strauss and on and on.

Punctuate: A significant fact about Arendt is that she knew everybody who was anybody. The list of her acquaintances in Berlin is mind-boggling: Marc Chagall, Edward Munch, Irving Berlin, Kurt Weill and Berthold Brecht, Albert Einstein, Alfred Hitchcock, Fritz Lang, Marlene Dietrich, even Fatty Arbuckle. That must have been fun, working with that cast of cameo characters. Is this a favorite moment in history for you?

Krimstein: “Scenes” fascinate me. What was it about Montmartre in the early twentieth century, Liverpool in the late 1950s and early 1960s, Paris cafes during the rise of the Enlightenment? Weimar culture is so, so important to modern art, the modern world. Theater, writing, collage, science, painting, film (an especial passion of mine, yes, I confess, Lang is a hero of mine). But when I discovered that the great Billy Wilder (another hero) frequented the same cafe as Hannah, the Romanisches, well it just kept getting better and better. And then, her scene moves to Paris, then to Marseilles, then, in many ways, to Greenwich Village and Hollywood. I always loved the book City of Nets, which described the bizarre artistic refugee community in Hollywood during the war.

Punctuate: During the phony war between the Allies’ declaration of war and the German invasion, Arendt was more attuned to the dangers that lay ahead than many of her compatriots. What role did their complacency play in the shaping of Arendt’s post-war thinking?

Krimstein: Arendt did not like easy answers. She didn’t like when people averted their eyes from the full measure of what was going on, and replaced it with “wishing and hoping,” with an innocent belief that things would just work out. Her innate toughness of thought would not let her gloss over the madness swirling around her. She was definitely, in my opinion, the kind of person who ran into fires.

Punctuate: The book really is a page-turner. Can you explain the complexities faced by Jews and other victims of the Nazis who sought to escape through Spain or other neutral countries?

Krimstein: The complexities refugees faced then are not too dissimilar from what refugees face today. Visas on visas on permissions for transport, a nightmare of bureaucracy, that on one hand has you believe if you fill in everything “correctly” you’ll be able to leave, but which can turn on you, willy-nilly, at any time. I make note of the fact that during World War II, just as the refugee flow was reaching full force, for some reason the United States severely restricted the number of refugees they would accept. And, again like today, many third-party sources rose up. Smugglers. Some honest brokers. Many, less so. I put myself in the position of people facing this; I wondered what I would do. Hey, I’m a good, law-abiding citizen. Who knows how that would have worked out for me? Escaping the Nazis was harrowing. It even forms the dramatic engine that drives Casablanca, one of the most compelling Hollywood movies ever made. (Remember the elusive “letters of transit”?) The plight of the stateless is, for Arendt, one of the most horrible, de-humanizing actions people can do to one another. It’s like banishment.

Punctuate: Page by page, the composition of this book is remarkable. Many of the panels are crowded with historical figures and footnotes, yet there are also moments of erasure, characters like Arendt’s father and Natalie Farkas, a girl she cannot smuggle out of Germany, are there and then disappear. Will tell us a little about your creative process in composing the book? Did your ideas about how it would look change at all as you drew it?

Krimstein: One of the wonderful things about telling a story in words and pictures—whether it’s a New Yorker “gag” style cartoon or a comic or graphic novel is that you have the language of images at hand. I spent many years working in advertising and design— compacting ideas, compressing them to create a situation where the words don’t tell the whole story and the pictures don’t tell the whole story. It’s a situation when only the right combination of verbal and visual information engages—as I sometimes tell my students at DePaul, an equation where 1 + 1 = 3. So, I had storyboarded the arc of the action, but as I put it down, first in pencil, then in pen, when a picture could tell more than words, I allowed that impulse to take flight. Sometimes it worked. Sometimes it didn’t. But, again, for me, that’s the magic of this kind of storytelling. It owes a lot to cinema I suppose. Maybe silent cinema mostly. Although, the early filmmakers who were bridging that liminal space between silent film and talking films really “got it.” Lang. Hitchcock. John Ford. Ernst Lubitsch—as Billy Wilder (him again!), one of his collaborators and perhaps his biggest fan ever, said of Ernst Lubitsch (think Trouble in Paradise—written by Chicago, ex-adman Samson Raphelson), “Lubitsch could do more with a closed door than most directors could do with an open fly.”

Another thing about the look—I used a mixed media form. I just liked the way it felt— pencil, ink, paint. And Hannah, well, she’s always dressed in green. (Incidentally, this came from research; evidently, she did favor wearing green.)

Punctuate: Many of Arendt’s contemporaries emigrated to the United States before and after the war. At this moment in time, when the very notion of immigration is under assault, what is your view of the contributions that generation immigrants made to contemporary American society?

Hmmm. Let’s see. Albert Einstein? Irving Berlin? Vladimir Nabokov? Helena Rubinstein? Enrico Fermi? Nikolai Tesla? Charlie Chaplin? Willem de Koonig? Elie Weisel? Igor Sikorsky? Lee Strassberg? Isaac Stern? Mark Rothko? Emma Goldman? Felix Frankfurter? Elizabeth Kubler-Ross? Dr. Ruth Westheimer? Etc. Etc. Etc.