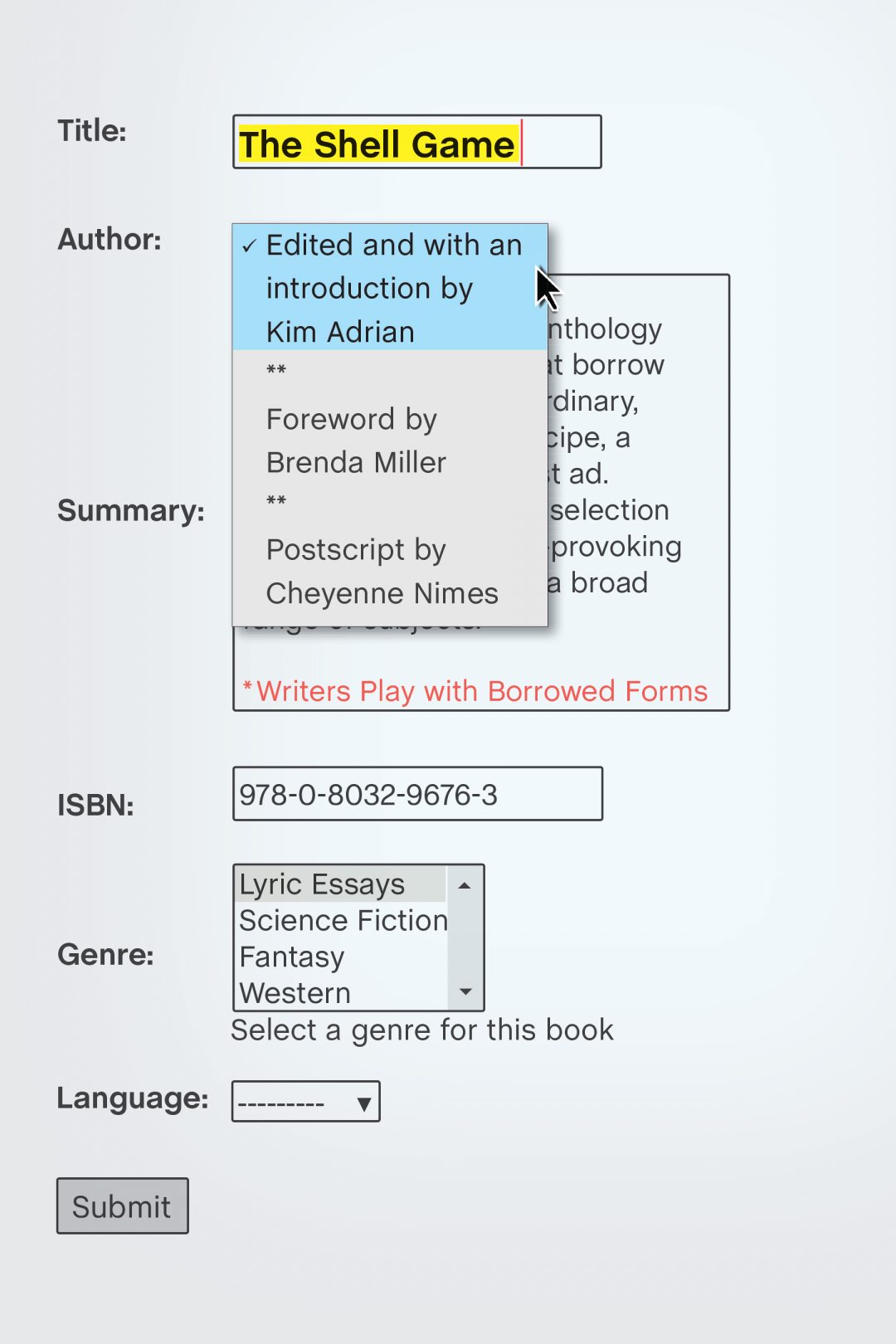

This survey was sent by Jenna McGuiggan to Kim Adrian, editor of The Shell Game: Writers Play with Borrowed Forms, published by the University of Nebraska Press.

Except for the book’s foreword, by Brenda Miller, and the source acknowledgements, everything in this anthology has been written using borrowed forms, including Adrian’s introduction, all of the essays, and the postscript by Cheyenne Nimes. There’s even an essay hiding in the list of contributors.

SURVEY:

Your answers to the following questions will help us to understand how this anthology of work by 30 writers came together. Your feedback on these topics is invaluable. Thank you for taking the time to complete this survey.

1) Which of these factors was most important to you when deciding to create an anthology of borrowed form essays?

A. The fame and fortune that only essay anthologies can offer

B. A postmodern distrust of traditional literary forms

C. A lifelong passion for crustaceans

D. Other (please specify)

Finding the right form for a given piece of writing is a huge but normally hidden part of the writing process. One reason I like to read and write essays that borrow their forms from elsewhere is that they put that aspect of the writing process front and center. To me, this anthology is ultimately less about this very narrow sub-genre, the so-called “hermit crab essay,” and more about looking very closely at the relationship of form to content.

2) In her foreword to The Shell Game, Brenda Miller explains how she came up with the term “hermit crab essay” in 2001 to describe lyric essays that take on the form (or “shell”) of another kind of writing. If the term hermit crab essay should fall out of favor, what other trickster of the animal kingdom has the necessary qualities to fill this role? Please consider the potential threats and predators that such a specimen would have to overcome.

A. Honey badger (“don’t care!”)

B. Ostrich (head in sand)

C. Possum (playing dead)

D.Chameleon (changing colors)

E. Octopus (master of camouflage)

F. Other (please specify)

I think the honey badger makes a great mascot for all serious writing. It’s tenacious, a little insane, it gets the job done, even if it almost dies trying. But most of all, it “don’t care.” That’s so key to writing well—outrunning your own demons. Finding a way out of their grip. Getting back up if you get knocked down, again and again.

3) In the book’s introduction, which is written in the form of an entry in a field guide, you write, “Like its biological cousin, the hermit crab essay is extremely vulnerable without its hijacked home.” You also note that the essay’s “shell” gives shape and structure to both enormous and tiny topics that might otherwise be too complex or insignificant to work as an essay. Which of the following statements best expresses your experience as a writer with this concept of finding freedom in structure?

A. “Freedom’s just another word for nothin’ left to lose.” (Janis Joplin)

B. Write free or die. (unofficial motto of writers in New Hampshire)

C. “Smokey, this is not ‘Nam. This is bowling. There are rules.” (Walter Sobchak in The Big Lebowski)

D. “Control, control, you must learn control!” (Yoda)

E. Other (please specify)

Finding freedom within a rigid structure is a curious phenomenon. I think it works this way because formal constraints help to streamline content—they give it direction and direction equals energy. The most dramatic instance of this I’ve experienced is the time I wanted to write an essay about knitting. I’d already been knitting for many years, so naturally I had a lot to say about it. But when I started trying to get my thoughts down on paper, everything felt extremely vague and inchoate. Then it occurred to me I could use the form of how-to instructions, and as soon as I’d plotted out about a dozen “how to” points, the content practically laid itself down on the page. But of course form is hardly the only stumbling block to finding your way into a piece. I’ve often experienced something similar with tone. If I haven’t found the right tone for something, it’s as if I’m locked out of the work. It can be incredibly frustrating. Like trying to find your way into a pyramid or something like that. There’s a secret door somewhere, but where is it? And is the key is a matter of form or of tone? Or both?

4) Some hermit crab essay “purists” avoid using borrowed forms that have already been used. Do you agree with this stance?

A. Yes

B. No

C. It depends (please specify)

Sometimes you can reuse a form over and over again and it actually enhances the effect. Michael Martone does this with his “contributor notes,” one of which is tucked into this anthology, hidden among the actual contributor notes. Martone’s project has evolved over time, and across an array of venues, to become a kind of autobiography in bits and pieces. It’s a fascinating project. And Cheyenne Nimes has success using different types of legal documents because her writing about the environment benefits from that kind of litigious set up. It gets the energy going and immediately sets the reader up for a kind of “fight on the page.” But whether you seek out the same form again and again, or use different forms, the main question to ask is whether there’s an affinity between the form and the content. Does the form you’ve chosen somehow augment, amplify, illuminate, or illustrate the content in interesting ways?

5) You wrote your memoir, The Twenty-Seventh Letter of the Alphabet (forthcoming this October from University of Nebraska Press), in the form of a glossary. What was your process for writing that book in that form?

A. Chose the form first

B. Wrote the story first

C. The form and the story magically appeared together, like a delicious peanut butter and jelly sandwich.

D. Writing is a messy, nonlinear process, all writers know that.

E. Other (please specify)

It truly was an incredibly messy, non-linear process. A total train wreck for a long time. I tried to write it from one angle, then another, and another, and another. I started over so many times, always searching for the door to the pyramid, and then for the right key to open it. I had terrifying dreams about literally being stuck between a rock and a hard place. I think these dreams were actually about the writing process itself. It just was so difficult for so long. For a few years, when things were super tough, and going nowhere, I started wondering if I might have a serious problem. I thought maybe I was a masochist—like a true masochist. Someone who was compelled to hurt herself, and the way I was doing it was through my writing, because the pain was so intense when I couldn’t find the door, and I couldn’t find the key. When I finally hit on the idea of using the form of a glossary, it was terrifically liberating. The story opened up and, much like the knitting essay, started laying itself down in little chunks. The writing was suddenly very free. When I’d written everything I could in this way, and then went back to reread what I’d done, I saw that there was still a huge amount of work to do, but at that point, it was just a matter of revision, not generation, and that was easy. At least comparatively speaking, it was very easy.

6) The essays in The Shell Game take such interesting and varied forms: a crossword puzzle; an approximation of a Rubik’s Cube; a variety of reports, instructions, and manuals; epistles; board games; computer code; questionnaires; lists and outlines; and footnotes. If reality were no barrier, what other borrowed forms would you like to see used for future essays? (Check all that apply.)

Clouds

A.Potter’s Wheel

B. Video Game

C. Opera Libretto

D. Velvet or Suede Pillow

E. Barbershop Quartet

F. Magic Eye Poster

G. Memes and/or GIFs

H. All of the above

What a great list. Please go on. (But I’d especially like to see an essay in the form of a suede pillow.)

7) As you note in your foreword, there is currently a “fascination with all things mixed and morphed.” Hybrid literary forms like the hermit crab essay seem to be having a moment. Why do you think this is? (Check all that apply.)

A. Globalization

B. Shifting gender lines

C. Economic insecurity

D. The Internet / Social Media / Age of Information

E. The rise of fake news

F. Writers just wanna have fun!

G. All of the above

8) Is there anything else you’d like to tell us?

Thanks for this survey! It was fun to do.

Thank you for taking the time to complete this survey. If you’d like to be entered to win the discarded shell from a live hermit crab, please enter your email address on the next page after you click submit below.

[SUBMIT]

Kim Adrian is the author of The 27th Letter of the Alphabet (a memoir) and the editor of The Shell Game (an anthology of hybrid essays), both from the University of Nebraska Press. Her book Sock is part of Bloomsbury’s Object Lessons Series. Her award-winning stories and essays have appeared in Tin House, Agni, the Gettysburg Review, Brevity, the Seneca Review, and elsewhere.

Jennifer (Jenna) McGuiggan is a writer, editor, and teacher. Her work has appeared (or is forthcoming) in Rappahannock Review, New World Writing, Flycatcher, online for Prairie Schooner and Brevity, and elsewhere. Find her online at www.thewordcellar.com.