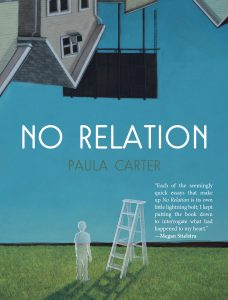

Paula Carter is the author of No Relation, a collection of flash essays that details her experiences helping to care for, and then leaving, two boys from her partner’s previous marriage. Incorporating prose poems, fairy tales, metaphors, and vignettes, Carter creates a mosaic of love and loss, longing and belonging, as she searches for the true meaning of family.

Paula Carter is the author of No Relation, a collection of flash essays that details her experiences helping to care for, and then leaving, two boys from her partner’s previous marriage. Incorporating prose poems, fairy tales, metaphors, and vignettes, Carter creates a mosaic of love and loss, longing and belonging, as she searches for the true meaning of family.

While No Relation is Carter’s first book, she also has essays published in The Southern Review, Kenyon Review, TriQuarterly, Prairie Schooner, and other journals. She is also a company member with 2nd Story, one of Chicago’s most prominent live lit events.

The interview with Carter was conducted over cups of coffee in her charming apartment in Chicago’s Andersonville neighborhood on an August afternoon.

SF: Nonfiction is a genre that is not so easily defined—especially when we consider the multiple subgenres that challenge its boundaries. Because No Relation is characterized as a collection of flash essays, I was wondering how you would define a “flash essay” in your own words?

PC: I think for me a flash essay is something that walks the line between prose and poetry in a way where the writer takes one significant moment—no matter how small it may be—and uses it to make larger connections to more universal themes. In this way, a certain theme is explored within a very short space and the subject matter becomes more immediate and crystallized for the reader.

SF: I really like that you used the term “crystallize” because it evokes the experience of how I read your emotions. In the book, you don’t overtly describe your emotions; instead, we catch these “glints” of an underlying emotional depth growing beneath the pressure of your prose. How did you write these crystallizing moments despite the extremely personal and emotional nature of the subject matter?

PC: When I began writing the book, I had written some standalone flash essays so I felt that I understood the tools of the form or, rather, the parts of the form. I had also read Safekeeping by Abigail Thomas which is written in these flash nonfiction moments and is also an amazing, beautiful piece of writing. I had all these feelings I wanted to express and when I read her book, I thought “This is the way I can do this,” because it allows me to share moments and construct scenes without a lot of explaining or exposition, which are great things in a regular essay, but, with this form, readers are asked to make certain connections themselves. I feel it leaves more space for reflection and interrogation. Also, without having too much exposition, I was also able to explore the power within my different relationships—with my ex-partner and with his two sons—in a more discrete way.

SF: What motivated you to take this dual experience of falling in and out of love with a romantic partner while also parenting his two children and turning it into a book of essays?

SF: What motivated you to take this dual experience of falling in and out of love with a romantic partner while also parenting his two children and turning it into a book of essays?

PC: The first impetus was that I had so many thoughts and feelings I wanted to express. I was so deeply affected by building my relationship with the boys and then having to leave them after my partner and I broke up. However, the second impetus was that I noticed there were not many books written from the perspective of a non-biological parent, or from someone who was in my position. When I was grieving the end of my relationship with my partner and his two sons, I was looking for books to help me cope and all I could really find were books in the self-help genre or books on how to create a successful blended family. I was frustrated that I couldn’t find many things written in a more creative genre or from the step-parent’s point of view, which led me to write my own essays about the experience.