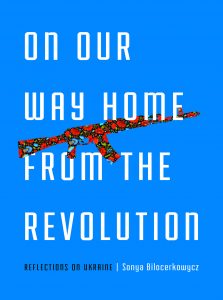

Colorful

Growing up in the USSR, I’m used to the scarcity of choice in clothes. I live in Leningrad, Soviet Union’s second largest city. Nothing sold in the stores has any aesthetic appeal. Shapeless pants – half denim, half dirt – cling together in the middle, a clump of awful pink blouses floating nearby, the entire space occupied by dreadful alternatives to what a normal person might consider good-looking. Even the sadly shaped pants are available only in XXL. We keep successful finds for years, patching them as long as possible. Once a year or two, Mom hires a seamstress to sew an outfit.

As a teenager in the 1980s, I’m reduced to a pair of gray pants and beige shoes. A few boring dark shirts and a pastel-colored T-shirt or two are all I own. I won’t impress anyone as a sharp dresser.

From the occasional foreign films shown in Leningrad, we have an idea of the apparel diversity in the West. I’m envious of the classmates whose parents have money or connections, allowing them to dress them in what we call feermennye clothes, which literally translates as firm-produced. Any firm is better than the rotting Soviet economy, where everyone supposedly owns it all, but owns nothing in real life.

*

It’s 1982. I’m fourteen. Dad spent a month in Prague collaborating with Czech scientists, resulting in a book, Ray Methods in Seismology. He brings a coat and a dress for Mom – and for me, a red waterproof jacket with detachable sleeves, a detachable liner, but an utterly undetachable cool factor. Its many pockets, its strange lines and inventive attributes, its small sections of black, its hood – all these features make the jacket immediately recognizable as a foreign item, even if it was manufactured in another country of the communist block. Apparently, their communists hadn’t managed to mess it up as thoroughly as in the USSR.

For the first time, I feel special on my way to school, at least inasmuch as my looks are concerned.

“Molotkov, where did you get that jacket?”

I explain.

“Sell it to me,” a classmate says. “I’ll give you 300 roubles.” He’s not a close friend, but I respect him for his sense of humor and his moderation in interpersonal interactions.

“I can’t. It’s a present.”

I wouldn’t sell it in any case.

*

Out in town, I carry my things in a Marlboro plastic bag. Mom received it as a gift from a colleague who’d traveled abroad. It’s a sturdy design with handles that snap together – something one might call disposable in the West, as I will discover much later in life. On the bag, the sinister man smokes a cigarette, smiling at the legs of the passersby.

I don’t care – it’s a feermennye bag.

*

The gray world is sad but familiar. My two years in the Soviet Military, 1986 through ‘88, raise the stakes in terms of homogeneity. We are disallowed to supplement the shapeless, poopy beige uniform – called HB, after the Russian term for cotton – even with invisible items of attire, like socks. In winter, a long, awkward overcoat completes the deal. It would suffice elsewhere, but Siberia’s temperatures range between -40 and 90°F.

“Molotkov, what is it under your HB?” The officer’s hand digs under my shirt like a rude lover’s.

“It’s a sweater, Comrade Senior Lieutenant.”

“Not allowed.”

“But it’s too cold without it.”

“No arguments, private Molotkov. Take it off and destroy it.”

“Tahk tochno,” I say, that way exactly, the Russian equivalent of Yes, sir.

I’m four thousand miles east of home. I despise the mentality that seeks to turn unique individuals into identical puppets, in look and in thought.

*

In 1988, I’m back in Leningrad. At twenty, I’m more than ever convinced that looking like everyone else is unacceptable. Mom passes on a pair of red shorts she wore in her youth. They fit just right. Shorts are rather infrequent in the Soviet Union, particularly on men. I enjoy walking about so dressed, especially considering the choice of color – the communist red on my ass.

*

By the time 1990 rolls in, I’m sick of the USSR, where lofty ideas are supposed to explain and excuse brutality. I’m tired of the sad outfits my country wears. More importantly, I’m tired of uniform thoughts. I can’t spend my life in this kind of isolation.

I decide to move to the United States.

*

In 1991, I’m in Albany, New York. I have a job and can afford a few brightly colored T-shirts, a fitting pair of jeans, shorts to replace my mother’s aging pair. This bundle costs me $45 at Ross – now I’m better dressed than ever in my life. It’s nice to be able to buy good-looking clothes, I mention in a letter to my friend Boris.

Before I know, this becomes a trope. Molotkov likes good-looking clothes. Molotkov wants to dress well. Ha-ha. The new American intellectual.

I’m not mad at my friends back in Russia for ridiculing my desire to elude the black-and-white-and-beige paradigm. They live in a world trained to think of such niceties as excesses.

As far as my future is concerned, the least desirable outcome is wearing a uniform again, such as a suit to a formal office job. I won’t be getting a job that requires suits.

*

In 1996, I move to San Francisco and expose myself to a broader range of lifestyles. To a person from the gray USSR, this place is both an imperative and an offering. I love the freedom – I might as well use it. Hair dyes enter my life.

Many people sport blue, pink or purple hair. By the late ‘90s, this is as much of a cliché as earrings in one ear, per George Carlin. I shouldn’t think conservatively. Rainbow hair is the only reasonable choice.

I feel vindicated as I walk about, my hair in the wind. It’s a slap on the face of my past in the USSR. It’s a symbol of freedom. But I’m a little embarrassed too, and it takes some practice to face the passing strangers in the same way as I would otherwise: neither seeking, nor obsessively avoiding, eye contact. Many people smile; I smile back. The occasional strangers make compliments. The truth is, I’m not doing this to show off, nor for anyone’s approval.

Or am I?

*

After a few months, hair alone seems a puny gesture. Why be conformist with 97% of my body surface? My full-color commitment begins. I hire a seamstress to sew two pairs of pants from four different sections of multicolored fabric. As I explain my order, the frown on her forehead keeps deepening until I’m ready to fall into it.

With rainbow pants and rainbow shirts to supplement my rainbow hair, I finally feel far enough from a uniform. Can I relax yet?

Wait a minute. Fingernails.

I stock up on nail polish.

I could say I don’t care what people think, but that would be simplistic. I’d rather not offend anyone needlessly. If no one were around, I wouldn’t bother with my appearance. The closest I can trap this in logic: I want to prove to myself, and signal to others, that I can live on my own terms inasmuch as appearance is concerned – and beyond appearance.

Whether I want it or not, my looks send a message. I hope no part of it is negative. I hope it encourages others to treat me, from the start, as an authentic person. I hope it inspires the occasional stranger to loosen up in their own life – not in color per se, but in somepersonal sort of freedom.

As months go by, I stop noticing others’ noticing. I feel transparent again.

*

In 2005, I’m in St. Petersburg, the city of my birth, no longer named after the mass murderer. Following my mother’s death last December, I’m going through the family apartment.

In one of the closets, I dig up the strange and stylish black shirt I wore in the 1980s. It boasts pockets on the sides and the front, along with an unusual collar that buttons up against the wind. It was Mom’s present, an item of elegance in the gray world. She’d spent hours in line to get it. I wore it to all the school dances; I wore it so much it developed an archipelago of minor holes. I bring it back to the States with me.

*

Laurie and I meet in 2007, via a now defunct slightly hi-brow dating site. It doesn’t take long for the topic of color to arise.

“I looked at your picture for a while before I decided to contact you,” she says.

“Why?”

“I wasn’t sure I could deal with the colors. The thing is, I cropped off your hair, and your face is so cute without all this craziness.”

“Why did you decide to go for it after all?”

“What you wrote in your profile was so compelling.”

As winter approaches and I don my rainbow pants instead of the rainbow shorts, I see distress on Laurie’s face.

“I can’t believe I’m going out with a rainbow astronaut. I really like you, you know. But this is just too much.”

“What did you expect?”

We don’t reach a solution. We’ve been dating only a couple of months; neither is ready to commit to big changes.

Several months later, I’m at Blockbuster. I’m picking up the next DVD of Six Feet Under when Laurie calls.

“Hello.” I assume she wants me to rent another film or show.

“We have to talk.” Her voice is stern on the other end.

“We do?”

“Yes. I spoke to my mom, and she says I have the right to bring this up with you, because it concerns me deeply. I can’t commit to being with someone who always insists on wearing colors head to toe. I need to ask you to reconsider or soften your position on that.”

“You had to call me to tell me this, even though I’ll see you in ten minutes?”

“Yes. It couldn’t wait.”

“Why is it so important what I look like? It’s not like I’m trying to make youwear colors or dye your hair.”

“I don’t have an ideological problem with it. It’s just that I don’t want to be the center of attention every time you and I go out. And besides, it’s such a shame; you’d look much more attractive without all these colors.”

“What exactly are you asking me to change?”

“The pants are the worst part. If you could wear a normal pair of pants or jeans, I think I could deal with the shirt and the hair.”

“And if I don’t agree?”

“Then I don’t think I can commit to a future together.”

I’m deeply threatened. I can’t allow this attack on my right to choose my appearance. On a formal level, I should be able to wear whatever colors I want – this right seems inalienable. Yet, almost instantly, my defensive inner voice hushes. I’m almost forty. Being stubborn is no longer interesting or important. Making compromises for a shared project makes much more sense.

“Fair enough,” I say into my small pre-smart-phone device. “If it upsets you so much, I should listen.”

“Phew. Thank you.” Laurie’s voice lightens. “I didn’t expect you to agree.”

I didn’t either.

Over the months and years, we negotiate. After a decade, I’m ready for a less drastic attitude. I wear my rainbow pants only when giving poetry readings. The hair remains the only constant. I bleach it every couple of months and dye it every few weeks. Fortunately, the dyeing routine is performed with a paintbrush and takes only a few minutes, with Laurie’s assistance.

*

In 2018, I hit fifty. I still don’t own a suit. I tend to wear shirts with a special touch: a slant, a pattern that contrasts positive and negative space, a decorative hood or zipper. These shirts are not rainbow-colored – just colorful. I wear normal jeans or pants. I prefer brightly colored shoes, but I choose them to match the rest of my attire – not to clash with it.

My hair has been surrendering in a radiating pattern. I don’t care about growing bald. And I realize: I no longer care that much about my rainbow hair.

It has become a cliché, like Carlin’s earring a quarter century ago. I see enough people around with beautiful rainbow hair to render me an old dude trying to look hip. Who cares if no one did this in the ‘90s when I first started? I feel mildly melancholy as with all trends that have caught up with us. But mostly, I feel indifferent. My life has never been about my looks, although some of it has been about my right to choose them. I must be more comfortable in my role as a writer, artist, immigrant, a person with unique thoughts – so comfortable I don’t need to show it, or to prove it, even to myself.

I might dye my hair again someday, if any is left. I’m keeping my extensive set of hair dyes.

It’s never too late to change colors.

______________________

A. Molotkov immigrated from the Soviet Union in 1990, at age 22, and switched to writing in English in 1993. “Colorful” is a part of A Broken Russia Inside Me, a memoir currently in search of a publisher. Molotkov’s poetry collections are The Catalog of Broken Things, Application of Shadows and Synonyms for Silence; his prose is represented by Laura Strachan at Strachan Lit. He co-edits The Inflectionist Review. Please visit him at AMolotkov.com.