Mother Saint

She was dreaming, and the whisper of heartstrings and gentle lullabies filled the blackened hallway like a mist slowly falling with each rise of her chest, a glow coming upon her face as the softened creak of footsteps sounded from down the hallway and her door opened slowly, inch by inch, until she could feel the warmth of heat on her cheeks and the presence of a stranger standing before the bed. Esme rolled over, away from the light and the shadow, and felt the heat now spread across her bare back, over the pale, smooth skin and then into the muscles and deep into the marrow of her shoulder blades. She was dreaming of school, when she was only a girl, but all her classmates’ faces were that of many animals combined, morphed into one another. Her closest friend that of a fish and its gills, a tiger and its mouth, an elephant and its skin (like one she had seen dying at the zoo when she was only a child, with greening cracks in its dry, scaly flesh). The fur of a zebra was smeared across her friend’s once-navy class uniform, dripping on to the floor with hairs as heavy as drops of paint. He was reaching out his hand to her now, and it was only human, but Esme was afraid—so afraid, staring at the young pink flesh wrinkled with fat and softness, fingers unfolding from the palm limp as squid’s legs, that she sat bolt upright in her bed. The stranger looked at Esme curiously and reached their fingers toward her head, but Esme got up off of the mattress and moved through the darkness, an orangey light now flickering out in the hallway, bouncing against the walls of her little room. She rifled through a basket on her carpeted floor and then through a drawer in her dresser against the wall, throwing stockings and garters over her shoulder. The light grew brighter and brighter and brighter. One of the nuns ran past Esme’s open door. Then one of the young orphan girls, too. And, soon, the hall was full of shouting and rattling and thumping against walls and door frames, shadows stumbling through the red-yellow light as it blazed blindly down the hallway.

“There’s a fire in the nursery!” someone yelled. “There’s a fire in the nursery!”

Esme calmly slipped on a pair of bloomers and tightened the red lacing around her waist and thighs. She pulled her chemise on over her head and walked into the clamor of the hall, her bare feet padding against the floorboards. The quiet crackling of fire murmured beneath the shouts of the nuns and unwed mothers and orphan girls as they careened down the white hallway past Esme and the charcoal doors that lined the walls. Their shadows danced black in the orange light, their faces tinged the color of apricot, their eyes glistening with panic. Esme walked slowly toward the nursery as they shoved past her. The door to the room was opened wide. She could see the ebony floor glowing with wavering orange lines as the fire burned in the white cradles. It crawled up the drapes drawn over the windows, smoke swirling in the air, tattered pieces of cloth swinging to the floor. She could hear nothing but for the snapping of the fire and the distant shouts of the women as they scurried out of the convent—and Esme thought they all must be dead: the children in their pinfolds, charred, gone. She approached the closest cradle, the fire within growling, reaching toward the ceiling. She could see nothing beyond the blazing flame, heat enshrouding her body again, but she could hear a soft whimpering begin to croon beneath the deafening roar of the fire, throbbing in her ears. She looked around herself and saw no one— a piece of the wooden ceiling collapsing to the floor in a puff of dust and ash, one of the cradles crumbling to the floorboards, engulfed in flame, everything shaded orange as a sunset trapped indoors. But then, suddenly, a great ball of flame floated up from one of the still-standing cradles, casting a dazzling red light upon Esme’s face, brown embers flying in air. And through the orange blaze she saw a small, blackened body begin to rise; its arms were spread out as wings, its head lifted to the ceiling. She saw its eyes slowly open, shining clear and white.

“The fire came from her fingertips in sparks, that’s how she did it.”

Esme tossed and turned in the mattress, the bed warbling with the squeak and creak of metal.

“Stay still.” Hands pushed into her shoulders. “Don’t move, dear. Stay still.”

“I can’t see,” Esme whispered, her voice rough and raspy, hardly sounding like her own.

“Just stay still, dear. You—Dorothy, hand me a sedative. Yes, there on the shelf. Thank you. And hold her, please.” A pair of soft hands pressed into Esme’s skin. “Yes, just like that. Now- now, Ms. Anderson, you must calm down. Stay still . . . . You’re going to feel a pinch, and I want you not to move, all-right? Hold very still.” Esme felt the tip of the needle against her skin and thrashed in the bed, kicking her legs and throwing her arms in the air. The soft hands pressed into her shoulders harder and more fingers came to curl around her wrists and her ankles and her hips, nails digging into her skin, holding her down. She shouted and cried and screamed—whispers and gasps drifting through the air, hissing in her ears.

“She’s mad.”

“She did it.”

“Hold her still.”

“I didn’t see her that evening. After supper we washed and we dressed, and those of us charged with the bastards went to the nursery and fed them, then put them to sleep—as we always did. By the time I was finished, no one else was awake and all the doors were closed so I went to bed. I never saw Esme leave her room . . . but hers was the closest to the nursery and . . . I heard footsteps in the hallway.”

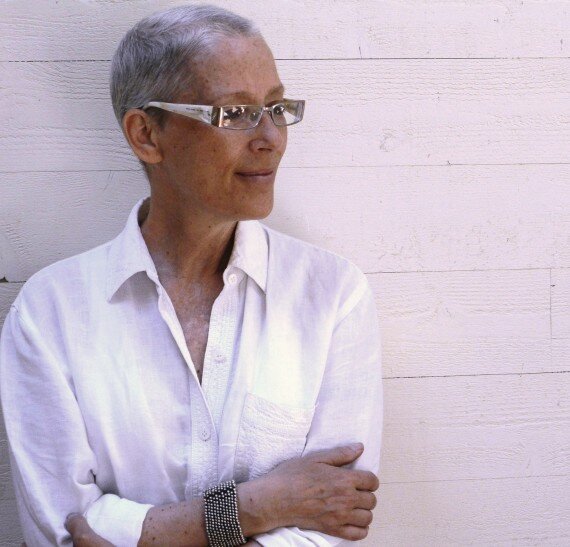

Sister Mildred was stroking Esme’s hair; it was blackened and singed, and the golden brown it had once been had dulled to a char gray. The strands were thick and uneven, looking as though they had been caked with dirt—and Sister Mildred said it would have to be cut. There was no way about it now. It wouldn’t grow this way and, if it did, it would be uneven and how would she plait it then? No, better to cut it off and start anew, she said. It would grow back before Esme even reached a hand toward her head. And, in any right, the nun said, she should thank God there was nothing wrong with her pretty face. She had no reason to lament.

But there was pain. It was crawling up Esme’s right leg, sharp and unwavering and her neck was flaring with searing pricks all over her skin, sinking into the muscles of her throat, shocking her bones. She couldn’t speak. Her words came out in harsh groans and whines like an animal was trapped inside her stomach, and she couldn’t move, she could hardly bring herself to turn her head. She lay so flat and so still on the mattress Sister Mildred thought she looked almost dead: callous with ash smeared over her pale skin. But Esme could see. Her vision was fogged and blurred around the edges, but she saw her little room: the white-stone walls, the little ornate lamp hanging over her bed, the black-tiled floors stretching toward the black door. There was a vanity of wood painted vaguely of teal, a small white-barred window with white drapes blowing gently in a breeze Esme could not feel, a white bedside table with a little drawer and a light-colored wicker chair beside it that was pillowed with blankets tinted yellow as teeth. She could see Sister Mildred kneeling before Esme’s head, her coral-beaded rosary clutched in one of her slim hands, the cross swinging over her knuckles as she spoke. It was the color of silver, but the carving had been rubbed raw with age and the passing of it from old to young hands: Jesus slowly beginning to disappear into the cross, deforming into a plain, smooth mound melded onto the crucifix.

Esme watched Sister Mildred’s knuckles shift from yellowish beige to pink and then white as she tightened her grip on the rosary. She was speaking, but none of her words reached Esme’s ears, humming a quiet monotone purr under the gentle whir of the ceiling fan overhead, her mouth opening and closing like a puppet’s, her tongue moving between rotting teeth. Sister Mildred’s face was fogged, in Esme’s bleared eyes, into a past youth that had once not seemed so distant. Her skin appeared smooth again, but Esme could still spy hints of wrinkles she had once recalled not being there and new purple crescents resting under Sister Mildred’s blue eyes, her thick blonde hair peeking out of her dark habit, making her appear more disheveled and aged than she had ever looked before. The nun smiled at Esme then, her lips stretched across her face—but misery waited behind her eyes, and Esme could not find it within herself to smile back.

The door to the little hospital room suddenly opened and in stepped two young nurses, clad in brilliant white. Behind them a man in a brown tweed suit was drying his hands on an off-white rag. He stepped in front of them, his clean-shaven face gleaming in the sunlight, tinted yellow like cream. He said something quietly to Sister Mildred and she patted Esme’s hand, standing from the floor, one of the nurses escorting her from the room with a wave of her porcelain fingers. Sister Mildred crossed herself as she passed the threshold, her black habit-skirt billowing out behind her, and the door closed with a gentle hand, only the second nurse remaining with Esme and the man, her rosy cheeks deepening in color.

The man said something to Esme, but his words were lost in the space between them, and he began poking and prodding her body, his cold fingers stretching her open eyes wider and squishing her cheeks to look in at her mouth and teeth. He examined her arms, lifting them from the bed and letting them flop to the mattress, heavy as a wet rag. He pulled back the sheet which had covered Esme’s body and examined her leg. Esme was still only in her bloomers and chemise, but the pristine white they had once been was now mucked with soot and ash and she felt no embarrassment come to her. Her leg was pink and red and angry and looked melted like wax dripping down a candle. The man pressed his hand upon it and it hurt, but Esme didn’t so much as flinch. She lay transfixed on the bed as a board, her arms at her sides, her legs stretched flat, all the while staring at the nurse by the doorway. Esme could see auburn curls peeking out from under the nurse’s white cap, little golden ringlets hovering before her ears. Her eyes were black as pitch and seemed to go on and on into the back of her skull, and her skin made Esme think of the ocean, the color of sea-foam as a storm rages somewhere out in the tropics. Her uniform was fading, the white tinged yellow and brown with stains, her skirt trailing to the floor, her blouse tight around her throat, her waist cinched, her sleeves rolled to her elbows. Her hands were folded before her, knuckles white as Sister Mildred’s had been. She stared back at Esme, her eyes unwavering.

“Nurse.”

She stepped to the man’s side. “Yes, Doctor?”

“Would you fetch me Nurse Haddington? And bring antiseptic. And”—the nurse nodded along as the man spoke, her dark eyes locked to Esme’s, not leaving them for a moment.

“She set the drapes on fire first and then she went and burned the children one by one, starting at their toes and then their blankets and then the wood of their cribs, and then she crawled up the walls and burned holes in the ceiling.”

The burn wound on her leg was cleaned and then wrapped tightly with pure white bandages. Her neck was plastered with creams and oils and cloths that smelled of citrus, tinny as metal, stinging her nose. They fed her little white tablets in the shape of ovals, smooth as a pebble found at a creek, with a swig of warm water to wash them down. But her injuries ached with hot pain still as if she were yet in the nursery, watching the fires blaze. Though, Esme could tell, from the light seeping through the drapes, that the sun was beginning to set and she was far from the gray walls of the convent.

The fading rays danced against the white of her little room, pink and orange and purple, shifting like the ripple of water in a pond, and Esme thought of the stained glass windows in the chapel—the blue and red and yellow that floated across the gray stone floors, rising as the sun sank, drifting toward the towering crucifix standing at the altar. Esme had never prayed there, she remembered. Truthfully, she could recall no memories of prayer to her mind, and she lay there quietly as her vision stirred, trying to summon one Hail Mary from the depths of her memory.

But when the black door to the room abruptly opened, Esme watched the light fall on the nurse’s face—the one from before, with eyes dark as midnight—and she was torn from remembrance. In her arms the nurse cradled a silver wash basin, a rag hanging over the edge with threads hanging loose, dripping water on to her skirt. She approached Esme lying flat in the bed, her heels clicking against the tile floor.

“I cannot believe they have not washed the ash from your face,” She said, her voice low and gravelly.

Esme only looked at the woman, her eyes straining to see all of her.

The nurse sat beside the bed in the wicker chair, steam floating toward her face in clouds of ivory. Esme wanted to say something to her, but her tongue would not move and she felt as if pebbles filled her throat.

The nurse reached a pearl-skinned hand toward Esme’s head, her thumb resting against Esme’s cheek, brushing the hair of her skin, wiping ash away. Esme stared at her, the nurse stared back. “I’m Dorothy,” she said suddenly, her voice quiet. “You can call me Dottie.” The nurse smiled, dimples peeking out from her pink cheeks. She soaked the rag in the water, white steam wafting around her head, and wrung it, warm drops splashing over the basin rim. Slowly, she brought the rag to Esme’s cheek, her fingers glistening wet like the reflection of a flame.

“She enkindled the fire. I saw it. I saw her do it. She had a fagot and a match, and I saw her light each crib aflame. Even the curtains—yes, she set the curtains on fire, and she wore no clothes, and then she went back to her room and fell asleep until we all were screaming. I saw her do it. And then she crept from her room when we woke her, and we had escaped. But she went back to the nursery and just stood there. She stood there. I could see her from window through the smoke. I think she wanted to die.”

The next morning Esme realized she had not stood since the night of the fire. Her limbs felt as though they had melted into the hospital bed and she thought of Sister Mildred’s rosary: Jesus bound to his cross, clutched in Sister Mildred’s warm hands, slowly fading. She thought of the imprint of her own body in the mattress, the outlines of her arms and her waist and her legs in the stiff, white fabric. She thought of Dottie’s hands pressing into her chest—wondered if they had left lingering pink marks there, blooming over her skin with lip-stick petals.

“I told them it was nonsense,” Sister Mildred was saying, her voice wavering, her hands shaking. “You were asleep—like us all. You were asleep.” Her cold hands gripped Esme’s still arm. “You could not have done. . . .” She looked at Esme, seeking, “You couldn’t have done . . . that. You couldn’t have.” Sister Mildred stared at her in the bed, the nun’s heart pounding in her chest. Esme’s eyes were rolled back toward her forehead, pupils glued to the ceiling, tracing the cracks in the stone. Sister Mildred thought the whites of her eyes glimmered something sinister.

“Esme, are you even listening to me?” Sister Mildred asked desperately, shaking the girl’s arm. “Hear me, O Lord . . . You didn’t do it, did you? Tell me you didn’t—you couldn’t have. . . .” Esme’s eyes flicked down to look at Sister Mildred. She stared at her for a long moment: the purple crescents on the nun’s face had grown longer and her hair had become more unruly, deep- set wrinkles Esme could trace with her fingers traveling across Sister Mildred’s skin in places they had never been before, waving and moving with her expressions. Her flesh was pale like snow and her lips looked almost blue; her face contorted as though she were honeycombed with agony in Esme’s stead.

“Vow to the Lord,” the nun said, “That you did not kill those children. Swear to Him.”

Esme opened her mouth and closed it. She looked deep into Sister Mildred’s blue eyes, “I did not kill the children,” She said, her voice ringing out clearer and sharper than it ever had before. This was the first she had spoken in days. “I didn’t kill them.”

Sister Mildred fell on to the bed, wrapping Esme in her arms, weeping into her chest, her tears warm and wet on Esme’s skin. “I knew you couldn’t have,” the nun said, “I knew you couldn’t have.”

“Esme has been with us for many years now. She’s a very good girl, always listens, never speaks out of turn—very pious; she attends every service we have. She’s very good with children. She would never harm any of them. She came to us with her own . . . burden. She found salvation in the Lord. After the delivery, it was adopted by a well-to-do family from New York. It is our policy that the mothers never meet the children, but Esme did get a moment to see it once before the babe was taken away. She handled it better than most of our mothers, and afterward she was devoted to God. She would never harm a child—no, not ever. She’s a Christian woman now.”

Dorothy came to Esme’s room with a pair of large, silver shears that twinkled in her hands like ice. Esme was still lying flat in the white hospital bed, unmoved since last the nurse had seen her. She felt as if she could feel Sister Mildred’s tears burned into her skin and she was peeking down at her chest, her eyes straining to see if there were any burn marks left there. When Dorothy closed the door behind herself as she came in, Esme’s eyes broke away from her skin in an instant. The afternoon light shone on the nurse’s face, warm and lemony, tinted through the drapes with a soft glow that made Dottie seem almost an angel, like one Esme had seen of stained glass at the convent, rosy and blue and sapphire, her white wings spreading out, her head tilted back toward the sky, her eyes black.

Dorothy set the shears upon the bedside table with a clink and began rolling up her sleeves, fingers curling the fabric underneath itself over and over. Esme watched her move, her eyes straining to the side to look at her.

“I’m going to help you sit up,” Dorothy said, placing her hands under Esme’s arms. “All right?”

Esme nodded, and the nurse lifted her up and set her against the pillows as if she weighed nothing, pulling the white blanket back up over her arms and chest when she was done. Dottie sat on the bed beside Esme, the mattress creaking under her weight, and ran a hand over Esme’s singed hair: blackened, uneven, each strand absorbing the afternoon sunlight. She took the scissors from the bedside table, one warm hand still resting gently on Esme’s head, feeling the bones in her skull and the delicate flesh of her scalp, and then began taking clumps of hair between her fingers, snipping them, the strands floating to the mattress and the floor in golden- black piles. Esme watched the hair fall before her eyes, Dottie solely focused on the shearing, the reflection of light in the silver scissors shining white on her face. Her hands moved slow and smooth over Esme’s skin, growing warmer and warmer the more hair that fell.

When she was done, Dorothy ran her fingers over Esme’s short-cropped hair. It was soft and glowed auburn like embers and Dorothy could feel the heat of her living, but Esme looked ill. Her skin was pale, and her cheeks looked thin and concave, deep-set, gray sickles sitting heavy under her eyelids. Her eyes seemed fogged as they darted over Dottie’s face, and she reached a hand toward Dorothy’s cheek as though she thought she was not really there—the white walls and the white bed and the white table and the pale chair and the faded vanity and the white-barred window with its white fluttering drapes glowing orange around them with a blinding brilliance that made Esme think of flames.

“There has always been something not right about that girl. She went mad when they took her son—did they tell you? Half-rats she was. She threw fits and barricaded herself in her room and attacked some of the other mothers. Once, Sister Laverne found her in the nursery just standing over an empty crib—weeping! She was bereft . . . . I didn’t see her leave her room the evening of the fire, but that does not mean she didn’t do it.”

That night, the moon shone silver through the little room’s window, casting a frosted light across the black tiles. Esme was lying in bed, staring at the ceiling, her fingers and neck and leg prickling with feeling. She could hear nothing, and everything looked still, silence echoing out around her with a resounding ring. But she felt the need to move deep within her muscles, as soon as Dorothy had left her, almost as if she were already floating up off the bed, her skin not even touching the sheets or mattress, though her only movement had been to breathe.

Beneath the door Esme noticed a soft, flickering orange light grow, spreading out over the silver moonlight, driving it back to the window, burning yellow. She was starting to feel a gentle warmth enfold her body, the incandescence growing as the light spilled across the tiles, beaming upon the vanity and the wicker chair and the bedside table, spreading to the feet of her bed and crawling up the mattress toward her legs. She felt a shifting of air suddenly as though someone were reaching toward her head, a soft finger brushed against her cheek, and Esme sat bolt upright in the bed, standing to her feet. She floated to the door as though she were hardly moving at all, and twisted the ornate, golden knob carefully, feeling nothing. Esme crept out into the hallway, floating down the white-tiled floor, the gray doors lining the walls all shut, all locked. The hall was completely empty and silent, but it glowed and flickered titian; the two white double-doors at the end of it flashing a blinding light around the edges, reflecting orange sparks and a lemony glow in the little barred-glass windows imbedded in the wood. Esme moved to them and stood before them, looking between the black bars of one of the windows. She could hardly see anything beyond the light, but she pushed the door open and stepped into the blazing room, her skin burning white-hot. Through the tinted orange glow, she could see beds lined around the walls of the room alighted, burning, fires growing toward the ceiling, and she could see several small figures standing in a circle in the middle of the room, looking down at a black mass that was aflame on the white tiled floor, yellow sparks flying toward their faces. The figures stood still, silhouetted, blurred. And Esme inched toward them, their forms becoming clearer, her skin growing hotter, her body beginning to ache. She began to hear a quiet murmuring beneath the crackling roar of the fires in the beds, humming out around her, incoherent words whispered through the air like the rising of fog with each falling exhale of her chest. As she got closer and closer to the figures, Esme saw that they were children, their faces that of many animals conjoined, merged into one another. One of them the face of an otter, the fur of a tiger, the mouth of a cat. Another the trunk of an anteater waving before the fire, the face of a dog, the scales of a gecko. The other two the face of a duck and a grizzly bear, the fur of a hyena and the feathers of a peacock, the mouth of a mole and the smile of a sloth. The four of them stood there, their skin and fur melting off their arms on to the floor, dripping heavy as drops of paint, leaving glistening puddles that shifted on the white tiles, reflecting the fires’ light. They all glanced up to Esme as she joined their circle, their faces blank, eyes hollow, tinted coral.

Esme looked at the burning shape they surrounded and saw that it was Dorothy consumed in the flames, her white blouse and white skirt and golden hair now blackened to the color of cinder, her skin still white as rough opal, shining almost like morning dew in the summer. Esme bent to the floor, reaching a hand toward her and Dottie began to rise, her arms and legs hanging heavy, her head slung back, looking to the ceiling. The wings of a raven sprouted from her back and the children all gazed up at her; her eyes slowly opening, bursting black.

Katie Johnston is a creative writing undergraduate at Columbia College Chicago. She has been an editor for the Columbia Poetry Review, a production editor for Hair Trigger Magazine, and her essay “The Barriers Faced by Female Writers” was published on the Fountainhead Presswebsite and won the Excellence Award at the Student Writers’ Showcase.