Come Away to the Water

Down along the riverbank

feet deep in sand

tread carefully and not too loud

for danger is at hand.

You hope to glimpse a water nymph

with slim legs and fair hair

but who you meet is something worse

she’s lurking in her lair.

The restless soul of someone lost

who died a death so bleak

in the lake she may have drown

or in spirit, so to speak.

With sallow skin and withered hands

and eyes as dull as stone

she’ll pull you down into the depths

this wicked water crone.

Her father knew this well when he made that bargain.

As he drags her through the mud, her bare feet slipping¾its cold bite feeling like that of an asp Eleanor sobs and pleads with her father to stop. The moonlight shines a path through the foliage, unphased by the cloudless night, it guides her father like a beacon. The stars twinkle above, unbothered.

Her mother scrubbed her down beforehand, her hands bearing buckets of water. Eleanor tried to fight when she was stripped, but this woman was not her mother.

Not with a face of stone and hands of iron. Not when she looked into those brown eyes and all she saw was the cold stare of hatred in place of the usual, gentle, passion and love.

When she was naked before her mother, she dumped the water on Eleanor and attacked her with brushes and soaps, not even hesitating as she washed her everywhere, even when Eleanor shrieked at her mother to stop.

Shaking and weak from the effort of fighting, Eleanor barely had any strength to retaliate, as her mother dragged a comb through her long, black hair, yanking hard enough that Eleanor’s eyes watered. Her mother left her hair unbound, and dressed her in a plain green robe. With nothing beneath.

Eleanor begged her over and over. But her mother might as well had been a stranger.

When she left, Eleanor tried to squeeze out of her bedroom door after her. Her father shoved her back in.

“You no longer belong to this family,” they both kept repeating. More for themselves than for her.

A sacrificial lamb for the slaughter.

Now the bath seemed useless, as her body is drenched with sweat from the trek, making the fabric of the robe cling to every hollow and curve, leaving little to the imagination, the chill of the spring night peaking her nipples. Muck is caked up to her ankles, and little scratches mar her ivory skin from the branches dragging against her like nails. Like claws, she imagined, trying to pull her back, pull her away from her father, from that lake, but they could not succeed.

She tries to wrench her arm free, but her father’s grip is like that of a bear trap. She continues to plead and beg to him, but he just stomps through the mud and brush.

Eleanor didn’t expect him to become so desperate, so pathetic. This past winter had been rough, and instead of staying in the village’s usual hunting and fishing spots, he chose to raid the Nymph’s Lake.

Swimming and fishing in this lake is forbidden due to the creatures inhabiting it. They would grab unsuspecting swimmers with their webbed fingers¾their jagged nails digging in deep¾and drag them beneath the surface before they could scream.

Supposedly, there are five who live amongst the reeds and lily pads. Eleanor rarely glimpsed more than their shining heads peeking through the glassy surface. They forbid anyone from fishing in their territory and attempts to drive them out had previously failed¾miserably. As a result, the lake had run dry: the water turned to mud, fish died by the hundreds, and eating them caused incurable disease. However, they make an exception when there is something they can gain. They like to bargain and trade; they ask for something in exchange for allowance to fish in their lake. In turn, the lake is now decorated with odd trinkets¾on the trees, in the cattails and bushes, buried in the mud or left on rocks.

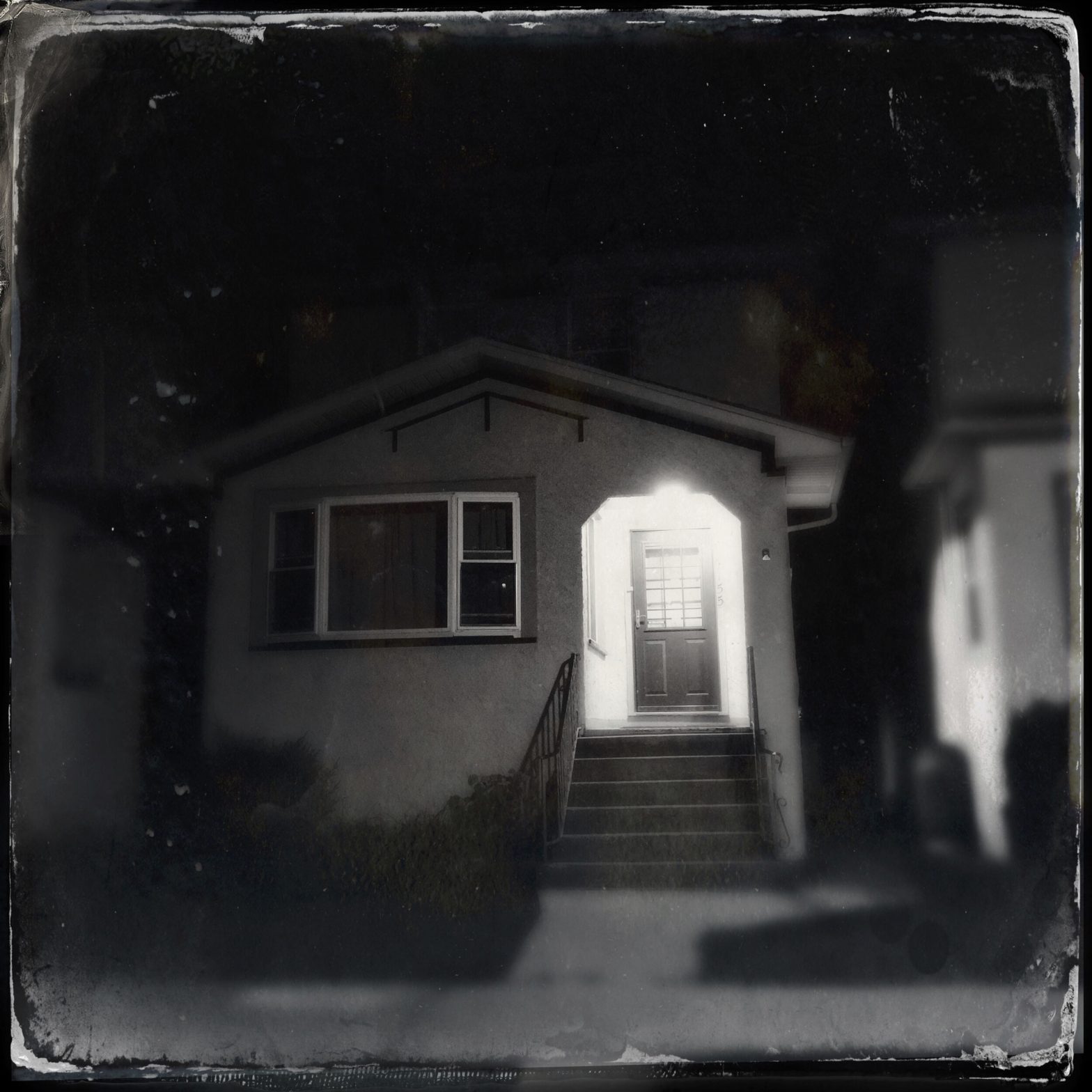

Under a large weeping willow, there’s also been a makeshift shrine erected between the roots. Eleanor can’t remember when there weren’t any flowers, candles, and fruits tangled between the roots as thick as her wrist.

Her father had made such a bargain with the nymphs, and when her mother asked how he was going to pay such a large sum, his cold, gray eyes only looked to Eleanor.

Her hair is still barely dry as thick strands of it cling to her back, dampening the robe. Her poor circulation leaves her skin as cold as ice.

Perhaps she should feel flattered, somehow. Her father would have to still think of her as valuable in some way if he’s dragging her there.

The glittering surface of the water emerges over the small hills of grass, between the birch trees and the curtains of the weeping willows. Its calm façade is a trap.

Grinding her teeth, Eleanor digs her feet into the cold mud and attempts to run. Her father hadn’t expected it, so one wrist slips free, and she doesn’t hesitate to rake her nails along her father’s hand, freeing her other.

Eleanor bites back her cries of pain as her torn feet slap into the sharp stones and dry branches. She hears twigs cracking behind her, and she only makes it four long strides before a strong and cruel grip locks around her hair.

Eleanor screams in agony as her father yanks her back, throwing her to the ground. Her cheek scraps along a rough root bulging from the ground, her hands skinned on the rocks. Lights dance in the darkness of her eyes, the world tilting. Warm blood dribbles down her leg from a cut on her knee.

As she rubs her head, her father is already there, gripping both her wrists in one hand, and backhanding her with the other.

Both cheeks stinging, he hauls her to her feet, and they continue towards the lake.

“No!” She roars, echoing across the empty sky. “NO!”

Eleanor can’t fight back against her father’s hands that move to grab her under her arms and drag her toward the calm water. She can feel the wind tickling her cut and bloodied feet as she kicks and thrashes, trying to claw her way free.

Closer and closer, he hauls her, like a bucking horse, toward the rippling water. Trinkets from other offerings dangle from branches or sit knotted to cattails, winking in the moonlight. The mud and sand are littered with more shiny things, others are too covered with mud to recognize.

She could see two waiting heads peeking from the water, eyes on the flap of the robe that falls open as she kicks, revealing her thighs, her stomach, everything to them. Eleanor sobs, even as she knows the tears will do her no good.

The heads submerge under the water, leaving little ripples behind.

Oh, gods. Oh, gods.

Eleanor yanks back one last time, falling to her knees, ignoring her open robe. She scrambles to crawl away, digging her nails into the mud. Her nails crack on the rocks as she continues to pull herself away. Her wordless pleas wrap her dirtied body. “Please,” she begs. “Please, father¾!”

Agony rakes across her head, scalp throbbing, with a slap of his hand. Pain ripples across her face, and she feels blood drip from her nose as she topples into the mud. A harsh blow to the face, so hard her teeth sing. She doesn’t have time to raise herself properly before her father grabs her by the hair again, right at the roots, the grip so brutal tears sting her eyes, and continues to drag her to the edge of the water.

As quickly as it happened, he pauses, but his hand still grips her hair. Eleanor angles herself to look at the lake, gripping her father’s wrists.

She nearly soils herself. The forest has gone quiet.

Standing at the center of the lake, is a slender, gray-skinned figure, staring with massive eyes that are wholly black. Like a stagnant pond.

Even when her father releases her hair, Eleanor can’t find it in her muscles to run. Immobilized by fear, she watches as the creature slinks through the water towards them.

She wears no clothes. Her long, dark hair hangs limp over her high, firm breasts. As she moves, the moonlight shimmers on her iridescent skin. When she stops just at the water’s edge, she lowers her delicate, pointed face towards Eleanor. Her nose is little more than two slits, and delicate gills flare beneath her ears.

Completely at odds with the childhood rhyme she had memorized when she was young.

Quivering like a leaf, Eleanor looks to her father, whose eyes are wide with shock . . . and fear.

The nymph stops just past the water’s edge.

“Speak, mortal.” She orders. Her voice is strange and hissing, her full, sensuous lips revealing teeth as sharp and jagged as a pike’s.

“I have brought an offering.” Her father says, his face like granite.

The nymph cocks her head to the side, those unearthly features devouring Eleanor. She had been told that the water nymphs eat anything.

Eleanor can’t hold herself up as her father shoves her to the creature’s webbed, clawed foot. Its color a molten grey.

“In exchange, I get to fish from here whenever I want.” He states. It was an effort to keep from gaping at the immovable face, at the pure command in the words.

“You would give me one of your kin, in exchange for access to my lake?” The sharp angles of her face accentuate those coal-black eyes.

“It seemed befitting for the amount of fish I gathered.”

A whimper punches its way out of her throat. Out of the corner of her eye, she can see the shadow of the nymph turn to look to her.

“But she is still your flesh and blood.” She says, taking a step closer.

A too-casual shrug of his shoulders. “One less mouth to feed. And we can always make more.”

His words are icy.

Eleanor huddles into her robe. If she hadn’t felt enough betrayal before, then this is what has broken her soul.

Her fear has now turned numb, solidifying her like stone as she clasps her hand over her breasts.

The mud has licked its way up to her knees, staining her robe, and sending a chill up her spine where it has soaked her lower back. The nymph takes another step closer, lined with preternatural smoothness. She beholds the disheveled Eleanor¾her dirtied legs, her scratched arms, broken nails, bruised wrists, and drying blood at the end of her nose.

Eleanor forces herself to look up at the creature. She can’t even find the words to defend herself. Her heart cracked, her soul shredded, her body grows still in acceptance of death. Her shoulders slouch and she takes deep breaths.

The creature’s face is as placid as the water’s surface. Perhaps even bored. Eleanor feels so exposed with this robe, and she bows forward, pressing her forehead to the ground. The nymph slowly extends her slender arm, a ripple of scales winking in the silver light. Her gills open and close with each steady breath.

Then she swipes.

Eleanor doesn’t scream, barely having the time, but ready to feel those claws tear at her throat. Instead, something drips onto the back of her neck. Eleanor opens her eyes to find that, she still has them, is still kneeling in the cold muck.

A garbled choking from behind has her slowly looking over her shoulder.

The nymph’s glittering hand has shoved through the throat of her father, puncturing it wholly. Her father still gives a garbled scream as the nymph slashes his eyes into ribbons with her other hand, his throat shredded seconds later.

Her father collapses face-first into the mud. His face looking toward her. Numb with shock, Eleanor can only stare in horror, her eyes welling. She soils herself and covers her gaping mouth.

Blood runs down the nymph’s hands, her forearms. Even though her father hasn’t moved, the nymph snaps his neck with a brutal crunch. Eleanor scrambles out of the way as the creature plunges her hand into his back, into his body.

Flesh tears, revealing a white column of bone¾his spine¾which she grips, her nails shredding deep, and breaks in two.

Eleanor trembles as the nymph grabs her father’s body by one ankle, and in a smooth motion, lined with restricted power, lifts it, throwing him into the lake like a pebble. His body crashes against the surface, and within seconds a heavy foam surrounds him, water lapping and splashing as the nymphs each take their bite out of him. A tainted puddle of red slowly blossoms in the water.

The nymph watches. Eleanor can only do the same.

Once the way is cleared, and the final bone of his body has been picked clean and pulled under, the nymph walks towards a group of cattails and cleans her hands in the mud.

Eleanor is still frozen, still staring at the water as the final ripple crawls across the surface. Her hands are shaking, face tingling, and her cheeks are raw from crying. But she can only stare. Only listen as the nymph sighs in disgust as she continues to clean her hands. She picks under her clawed nails, sneering at the blood, as if it is impure.

After another minute, the nymph is standing at her side. Eleanor doesn’t dare to look at her yet.

Finally, she mumbles, “Why?” Her voice hoarse from her screaming.

“Any man who betrays his kin in greed is unworthy to fish in my lake.” The nymph hisses.

Eleanor doesn’t bother to stand.

“You may go back to your home. We’re done here.” The nymph says, water lapping as her feet enter the water’s edge.

“No,” Eleanor blurts out before she can stop herself. The nymph pauses for a moment, the water having reached up to her ankles.

Eleanor folds her lips in as the creature stares at her with an unnatural stillness. When her eyes flick to the puddle beneath her, Eleanor’s cheeks redden.

She forces herself to her feet. “M-m-my mother, she’s the one who dressed me . . . like this. She didn’t stop him. And, and after what he said, I¾I can’t go back. I don’t want to go back.”

The nymph turns to face her and asks quietly. “Where will you go?”

Eleanor ponders for a moment, daring to touch the abyss of silence within her. “Anywhere,” she then says. “As far away as I can get.”

“And what would you do?” The water quietly trickles.

Eleanor shrugs, and realizes that the creature is standing a mere foot away from her. The creature takes a step back, seemingly surprised by her own approach. She’s a few inches taller than Eleanor.

“Live my life, I suppose. Live it the way I want to. Attempt to get back to normality after . . . this.”

“How far would you go?”

Eleanor looks to the night sky, for the first time admiring the glittering sea of stars above her. “I’d travel until I found a place where I won’t even think my parents. If such a place exists. And I will never come back.”

Not since her parents had been so willing to slaughter her like a simple farm animal. Eleanor huddles into her robe. She’ll have to go back to the cabin to fetch some of her better clothes¾if her mother hasn’t already thrown them out. If so, she may just resort to stealing from their deposit box her mother keeps under the sink. Eleanor breathes, attempting to numb herself, distance herself from these people; to no longer make them her parents. Just strangers.

The nymph is simply watching her.

“Here,” Eleanor pulls the silver band from her middle finger. It was a gift her parents had given her when she turned eighteen four summers ago. She offers it to the nymph, “Take this.”

The nymph’s eyes widen, frowning at the ring shining in Eleanor’s palm. “For what?”

“For saving my life. It is nothing compared to what I should give you, but it is all that I have.”

With a final assessing look, the nymph’s cold, clammy fingers brush against Eleanor’s, gathering up the ring. It glimmers like light on water in her webbed hands. “Why?” She asks, her voice slithering over the words, and Eleanor shivers again as the nymph’s black eyes threaten to swallow her whole. “This could’ve brought you some form of profit if bargained right. Most likely enough to leave town, or to buy a new dress.”

“There was no guarantee, anyway. Besides, that’s the deal. You helped me, and I give you something in return.” Her voice is so small, so broken.

A cold breeze has Eleanor trembling and huddling into herself, trying to secure any kernel of warmth. It’ll be close to a mile walk back to the cabin. It will be a miracle if she can make it. Her feet are throbbing from the cuts of hidden stones in the mud, and if they get infected . . .

Then she has to worry about any poisonous plants that her bare skin brushes up against, possibly having to find some place to settle for the night. Then she may be able to sneak into the house while her mother is gone.

“Perhaps I could interest you in another method of payment.” The nymph suddenly says, stepping close to gently grasp Eleanor’s elbow. She pauses, quite stunned at the soft touch. Slimy, yes, but gentle, as if she’s grasping an egg.

Eleanor’s shaking begins anew as she takes a deep breath, and wordlessly begins to open her robe, the folds falling off her shoulders. The nymph stops her with a webbed hand on her wrist.

“Not that. Something else.” Eleanor could’ve sworn there was a smile on the nymph’s lips. Eleanor’s cheeks warm with embarrassment.

“Then what do you ask of me?”

“The currents of the water hear all, speak all. They whispered to me of your father’s interest in this lake.”

Eleanor blinks back the sting in her eyes, adjusting the robe. “What of it?”

“I had asked for company as payment for his bargain.”

Eleanor opens her mouth, but then says, “To . . . eat?”

A laugh that makes Eleanor’s skin crawl resounds. “To tell me of the surface life. I was curious about it.”

“Why didn’t you say anything?”

A shrug of those slim, gleaming shoulders. “He never asked. So I was interested to see where his choices would lead him. And well, we can see how that ended.”

For a moment, her anger is solid and boiling, but she also understands. Her father could’ve taken her words in any way, and due to their reputation, immediately it went to the worst outcome. “What does this have to do with me?”

“I would still like the company. This lake is big enough for another affiliate.”

Eleanor’s eyes look to the water, then to the nymph. It is her turn to ask, “Why?”

A nod. “You have a strong heart. Compassionate and kind. Gentle and sweet. You look at the hardness of the world and decide to love and to be kind. You gave me your last possession, instead of using it to your advantage. It is a different form of strength that is underappreciated.”

A ghost of a smile widens Eleanor’s lips. “And, how, exactly will this be able to happen?”

The nymph smiles. “Have you heard of the legends stating that a nymph’s kiss can save sailors from drowning?”

Heat stains Eleanor’s cheeks. “No, I have not.”

“Because it is something we only share with people we like.” She is mere inches away, her webbed feet buried in sand. “The choice is yours.”

Eleanor looks back towards the trees and foliage, as if she can see all the way back to the small cabin just at the edge of town. She looks back to the water nymph. “Will it hurt?”

The nymph smiles widely, and Eleanor must resist the urge to take a step back, as she leans forward. She lifts her hand to caress Eleanor’s cheek, catching a stray tear she didn’t feel. She takes a quick breath as the nymph places her wet lips on hers. She smells of fish, but the scent mingles with fresh lilacs and roses.

The kiss sends a zinging current snapping against her skin, and as it crawls with goose bumps, it feels like a ripple that is slowly washing away her human blood until it is smooth like sand, molding her brittle bones into fresh steel.

Her lips are hot and soft against hers¾tentative¾even when the kiss deepens. Her clawed hand traces along Eleanor’s cheek before resting at the nape. There’s a tickling sensation just below her ear, and it’s enough to make Eleanor gasp, breaking the kiss.

The nymph takes a step back, smiling softly. Eleanor’s hands fumble to her neck, and she hisses when her nails scratch against an open flap of skin. When she inhales, the air tickles, and she can smell everything. The wet mud surrounding the pond, the freshwater lilies in bloom, the shift in the salty wind as a storm approaches. She can also smell her father’s blood, lingering near the center of the water.

When she looks to the nymph, she is only smiling with joy. Unfiltered joy. She extends her webbed hand.

When Eleanor looks to her own, she hadn’t realized she’d stiffened her fingers together. When she slowly opens them, the webbed skin between them stretches. Strong, and taut. Her cuts and bruises have healed, her nails having regrown into points. Not one stain of crimson on her now-shimmering skin, like that of a pearl. In the moonlight, she can see patches of scales already pressing through her skin, as if in an attempt to shed it.

“It will take your body some time to process the change. There will be growing, and shedding, and adapting.” The nymph says softly.

Eleanor looks to the outstretched hand. Slowly, she discards her robe. The chill of the spring night is gone. Replaced with a breeze that sings to her, that whispers bouts of warmth and salt.

After another moment and a deep breath, she takes the nymph’s hand. She follows her hip-deep into the water, and the nymph says, “Welcome home, sister.”

With one final exhale, Eleanor dives headfirst into the water.