Peanuts and Palm Trees

Tayler and her mother, Sherry, greet me at the baggage claim. Tayler’s long blonde and brown hair is piled on top of her head, and she is still as pale as when she moved from Kansas to Hawaii. Sherry’s hair is redder than I remember, lightened by her days spent in the sun. They are all smiles and teeth. I am smiles and lips. I watch the suitcases flow past the three of us until mine arrives, an American flag ribbon tied to its handle. They ask me how my flight was while Sherry grabs my suitcase from me. I tell them that it was okay, but that it felt longer than last year. As we walk through the airport to their car, I realize how much brighter this airport is than the one in Kansas, how many more windows there are. I watch people place leis on their friends and family, welcoming them to beautiful Maui.

Tayler and I are the type of friends that can go months without seeing each other and pick up right where we left off. This is rare and cliché at the same time. She moved to Hawaii two years ago because her mom got a job offer. We pick up where we left off in the car ride to their house, watch palm trees quickly pass from the rolled down window, and the white tides hit the sandy shore. She has a new boyfriend; he’s Asian she tells me. I don’t have a boyfriend like I did last winter, the last time I visited her. He was a dick anyway, Tayler says. I smile and agree. He left me for college. He left me for college girls.

I want to tell Tayler that I’m in a new relationship and I’m sorry that I didn’t tell her I was bringing Her along. She’s a friend, a companion, a partner(?), a person. We don’t have a sexual relationship, but I would call it romantic. I think She has romantic beliefs, this idea of perfection, that I can reach perfection. I can reach perfection with Her help. She tells me when I’ve had enough, when I’ve had too little. She lets me know what people think of me even if they don’t say it; she’s basically a mindreader. She looks a lot like me, only skinnier, but we don’t think the same. At least we didn’t used to. She has started to make me think things I never have before, to consider things about myself that could be easily improved if I would just try harder, listen to Her more. She has started to scream. A scream too loud to ignore, stomach-churning and always present. Her voice is acidic. I couldn’t have come to Hawaii without Her even if I tried. She can’t be left behind.

I know what’s best for you, Brooklyn.

That muffin isn’t what’s best for you! That carrot is, but only two. You know that.

I always said that I knew.

I don’t tell Tayler about Her because I can’t make it make sense in my head. We ride in Sherry’s jeep and let our hair knot itself on our heads. I look at the rocks lining the highway, creating a mountain. They are tied so that they don’t fall on cars and people. They are held hostage. I put my hands up and take Tayler’s picture from above. The air is warm even in motion.

The plane ride to Hawaii was painful. While I’ve been on longer plane rides than eight hours now, at the age of fifteen and sixteen, it felt like death. My father dropped me off at the Kansas City International Airport and hugged me goodbye. I yelled at him to drive safe on the icy backroads as I sprinted inside the airport to escape the falling snow and painful wind. It was my second time flying to Hawaii, but the first was easier than now. There were two people flying this time, and they had to share a seat and a brain. I could only watch Mary-Kate and Ashley films for so long before She told me I needed to eat; my metabolism was going to slow down.

Planes do not offer you easily digestible food. They give you a package of seven peanuts from 1999 or stale pretzels, probably also over ten years old. I put one peanut toward my salivating mouth, testing Her waters. I eat one; She says nothing. I smile to myself. I win this round. They taste old but salty. They are the stale type of chewy, easier to chew than nuts should be. I eat another, and another, and another until there is only one left.

Disgussssting Fuckinnnng Piiiiiiggggg

I drop the bag to the floor. The last peanut rolls out, goes under the seat in front of me, and toward the front of the plane. I close my eyes and run my fingers through my hair and pull. Please, stop. I whisper. Please, stop. I whisper. Please, just stop. I whisper. The guy next to me must think I’m insane. I spend the rest of the plane ride staring at my portable television screen, but not seeing a thing.

When we get to their house from the airport, Tayler suggests that we go to the beach. I walk through the kitchen near her bedroom and look at the Spam lining the walls, and the pink and yellow leis hanging on the corners of picture frames. Her bedroom is clean and small. I toss my suitcase onto her bed and shuffle through it, looking for a specific swimsuit. It’s black, small, and has a gold flower tying the strapless top together. I think it makes me look the skinniest. It is the skimpiest. I push a blue headband onto my head and pull back my long dyed blonde hair. I cover up with a strapless striped dress. Sherry comes with us to tan and take our pictures.

We pose in front of the beach sunset, arms around one another. The sand is hot on my feet and I keep bouncing from one foot to the other to lessen the burn. The water is bluer than blue; it is the clear type of blue. People shuffle around me and Tayler, also posing with arms spread wide in front of the water and sun. I see a lady jumping in the air, trying to get a shot of her flying. I am always turned to the side, sucking my stomach in. We try to make a heart with our arms, encompassing the sunset within them. It turns out looking more like a blobbed circle, and the next picture is of us falling over, laughing at how dumb we must look.

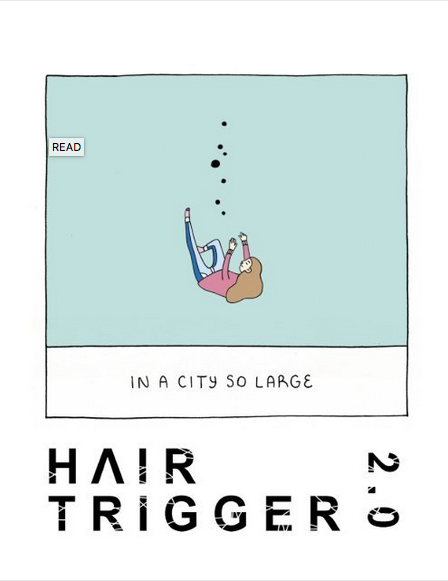

Sherry brings the camera over to us to show us the pictures and my stomach aches. I think about what She will say to me. Tayler leans against me as I flip through image after image. Tayler and Sherry say, “That’s cute,” and I nod. Pictures of us bent over laughing, hugging, me on her back. The ocean is vast and endless behind us; the sun’s reflection shines on its center. Sand covers my toes and butt, and there are a few photos of me trying to wipe it off. I cannot find a picture that I truly like. My eyes begin to well with tears. I want to be under the ocean. I want the salt of my eyes to be useful and invisible.

I sit in the warm sand next to Tayler. It burns my butt and thighs in a good way. I pick the sand up and let it fall through my fingers. The next time I pick a fistful up, I grind it in my hand. I rub my thumb over the inside of my four other fingers and let the sand dig into my skin. I do it until there is no sand left in my hands. And then I do it again.

You looked disgusting in those pictures.

I know.

Salad is the only option for the next few days. You have to have at least one good picture of you. You can’t look that fat.

I know.

Do you?

I want to scream I know. She will not leave me alone. I want to tell her that She isn’t the one living with this body; I am. It is different than living in this body, a body I did not invite Her into. Living with this body is a constant reminder that I may never be alone again, that there will always be a voice telling me that I can be more. There is always a more. There is never an enough, a quiet moment of peace. My body is a temple, but She said it’s too big; I have to be small enough for her to always find me. Living in this body means that She can bark orders, but I am the one that must follow through.

Right before we leave the beach, I look at my Timehop—a phone application that allows you to see what you posted on different social media platforms a year or more ago on the same date—I see a photo of me in Hawaii a year before. I am wearing a blue tube-top and denim shorts. My smile is wide and white. My hair is long and full. My stomach is not sucked in and gaping. My hips are not blades. My arms are not branches. The ocean behind me is still a clear blue.

I am not disgusted by what I see. I am not shocked. I am about thirty-five to forty pounds heavier in this photo, but I am more surprised by how my smile shines. I do not yet understand the feeling of my body taking up too much room. I do not want to disappear. I am there. I am unapologetic.

I recall the first time She spoke to me. It may not be the actual first time, but in my memory, it is. It was during lunch my freshman year of high school—about six months after my first trip to Hawaii, and six months before my second trip—Emily had asked me to come get a cookie with her. I had done this every other lunch period since the beginning of school, nearly five months before.

Don’t do it.

I told her that I didn’t want one today. She was confused, asked me what made today different. She reminded me that we always shared a pack of cookies.

I remained planted in my seat. I could not budge. I ran through the reasons in my head: I wasn’t that hungry today, I’m on a diet, I think I’m allergic to chocolate. Emily glared at me. She waited.

Good job. You don’t need that cookie. Just tell her to get the pack herself and save the other one for later.

I told Emily and she scoffed at me and walked away. I shut my eyes tight after that to think. What did I just do? I did want a cookie, but I couldn’t do it. I couldn’t because of Her.

This was our first memorable meeting, the beginning of a relationship that I didn’t know how to end. It was more than just physically and mentally abusive. It was inescapable. It was not inevitable, but She snuck up on me. She smelled the beginnings of my fear of food, of fat. She serenaded me with words of my potential, You could be so beautiful, if only you were skinnier. You can be skinnier. She courted me with invitations to the gym—invitations that eventually felt more like orders than requests. She won me over because She is me. And because She is me, She is here for as long as I am.

Emily did not ask me to get cookies with her again. I think she knew, or saw. Emily, like many others, stood by and watched my body dwindle: my skin, with the slightest bump, bruised like an apple, my hair thinned and fell out, and my teeth chattered in a warm room.

The beginnings of my disorder are confusing and blurry; minds do not work without fat, most memories do not stick. People don’t know what to do with a body that takes up so little space, a body that hides behind layers of clothing. My friends didn’t know how to be gentle with their touch. They saw it as a refusal to eat, but it is an inability. If only they knew Her, understood us. Maybe then they would have said something, come with us to the gym.

After I finish looking at the old photo on my phone, we leave the beach and go to Subway. Tayler orders a sandwich with pepperoni. I notice because I love pepperoni. When I was a kid, young enough to still have my parents buy my every meal, I always ordered a pepperoni and mayonnaise sandwich from Subway. Nothing else. No vegetables, cheese, other meats or sauces. This time I order a salad with every vegetable on top, no meat or cheese, and fat-free dressing.

Tayler tells me she didn’t even know they sold salads here. I shrug, tell her, yes, they do. Sadly. I thought that if they didn’t, I would be able to trick Her, tell Her that I had to order a sandwich. It was all they had! And I needed to eat! But there was a salad on the menu, and She saw it first.

You know you have to get that, right?

I know.

No ranch or anything, though.

I know.

We eat on a picnic table by the beach. The sun shines behind Tayler’s head, making her look more like shadow than person. I devour my salad because I am hungry, and then watch Tayler eat her sandwich. I cannot look away; the pepperoni shines like gold. The lettuce in her sandwich probably tastes better, although it is the same lettuce that’s in my salad. When she finishes, she asks if I’m still hungry. No, I tell her. She tells me that she noticed that I watched her eat, like I needed something more.

It seemed tradition now to get Subway on my first day in Hawaii. The first time I visited Tayler here, a year ago, I laughed when she suggested we get Subway for lunch. I wanted something Hawaiian, special. I imagined virgin piña coladas and kabobs with grilled pineapple, dancing ladies in hula skirts and coconut bras, and of course everyone greeting me with “Aloha!”

Tayler told me there was nothing like that near the part of the beach we were at, but there was Subway. I remember saying something like, “Okay, fine. But we better eat some kabobs for dinner,” and we did. Kabobs with grilled bell peppers, chicken, and steak. I ate them for dinner that night on a restaurant balcony next to Tayler, watching tanned women dance on the ground floor below.

On my first Hawaiian Subway trip a year ago, Tayler and I walked into Subway both knowing our order. We each got a footlong Italian sub on white bread and then decided we definitely also needed ice cream. It was hot in Hawaii, but not the bad type of hot. It was the type of heat that warmed your back, but not enough to make you sweat.

My ice cream was a swirl of chocolate and vanilla. I ate it quickly before it melted onto my hands and made them stick. Tayler had some too, but I’m not sure which flavor. I think it might have been pineapple. I remember something about her skin matching its glow.

During my second trip to Hawaii, I wake up around seven in the morning the entire week-and-a-half I stay with Tayler and her mother. I throw on some running shorts and a t-shirt, head to their backyard, and run in circles for an hour. I try to run around their neighborhood the first morning, but I get nervous. I think about getting abducted or lost.

On my first morning, I only make it down their street before I crush a tiny lizard at my feet. I jump when I hear its squish and rub my shoes on the concrete, ridding of its guts. When I begin to jog again, a middle-aged man runs past me and smiles. I give him a nod and turn around, start heading back towards Tayler’s house. There are so many people running around me that I begin to panic, wonder if they are watching me. Judging me. It doesn’t help that the sidewalk I’m on is next to a busy street. The cars whip past me and make my hair fly. I run faster, trying to catch it.

Where are you going?

I can’t run out here.

You better run at Tayler’s then.

I know.

Their backyard is pretty, at least. There are green trees lining the fence and fruit has sprung from its branches. It doesn’t look ripe, but it will be juicy and fresh. I think they’re are lemons or maybe apples. I run around the trees, touching their trunks as I sprint past each one.

On the third or fourth day of my running, Sherry comes out and asks what I’m doing. I tell her that I am just getting some exercise, and she asks why I do it in their backyard at seven in the morning. I shrug, go back to running. She doesn’t ask again, Tayler and I don’t spend much time with Sherry on this trip. I have to get three miles in. I’m used to being dizzy, so the circling doesn’t bother me.

Three miles in a circle.

Three miles at seven in the morning.

Three miles before Tayler wakes up and asks me what I’m doing.

Three miles because She woke me with her bickering.

Get up and fucking run. Vacation doesn’t mean you get out of it. Pig.

A year before, Tayler and Sherry didn’t live in this house. They moved from one part of Maui to another. Not too far away, but far away enough for it to be new. I remember how crisp Hawaii looked when I arrived. The palm trees, a type of tree I had never seen, stood tall and dangling. Their leaves mostly green, but some brown with decay. Tayler sent me a coconut in the mail when she first moved; she signed it with all of our inside jokes and nicknames. TurkeyTayler. Brookie. Tornado night. I let it rot in my closet, but it never started to smell bad.

The grass was greener, the sky clearer, the air more breathable than Kansas. I remember being excited to wear only shorts and dresses, to know that the weather remained at an almost steady eighty degrees. I wanted to take hundreds of pictures of us and post them to Facebook. I wanted to write my boyfriend’s name in the sand and sign it with a heart.

Tayler’s first house was smaller. It was brown and her bedroom was decorated with Hawaiin things, like colorful leis and ceramic pineapples. We spent most of our time outside, but if we were at her house, we used her webcam to talk to people back home, and with strangers on Omegle. We skipped past the perverted men and talked with guys our age for hours. We ate peanut butter and Nutella out of the jar and off a spoon. We spread their stickiness on crackers and made our mouths dry with food and laugher. We finished a large jar of peanut butter in five days.

We never woke up early and we always went to sleep late. We’d stay up taking mirror selfies, dying our hair with pink Kool-Aid, and planning our next couple of days. They all included tanning and food. They all included us taking pictures of each other and getting a henna tattoo of an anchor. They all included us laughing and talking about how blue the water is. That clear type of blue.

I met Tayler through Myspace, an old social media platform. She was new to our middle school and I had seen her around, but never spoke to her. Then she sent me a friend request. I accepted, honestly thinking it was a fake profile because her profile picture was so pretty, so clear, and not a selfie. Her skin was porcelain white, her hair straight, full, and long.

She sent me a message soon after I accepted her request: “The turkeys stole my macaroni!” I opened it, confused, but laughing. I replied with something like, “Oh, no! You need to get a new lock on your door. Turkeys don’t understand locks.” After we talked about the turkey situation for another fifteen messages or so—eventually concluding that turkeys were a bit evil—we introduced ourselves to one another. We were inseparable after that.

We spent every single day together, either walking to her house after school, or getting my dad to pick us up and take us to my house. The venture from school to her house was always the same. We would stop at the park, take photos of us looking emo and scene. Caption them on Picnik with things like: “Everyday you must smile.cry.and think. Even if it takes all you have,” and “Girls look me up & down & don’t know what 2 say. But it’s funny how the words come out, when I walk away.” In most of the pictures we are both in either red or blue skinny jeans, with fallen leaves or snow on the ground by our feet. Tayler and I were about the same size, so we shared a lot of our jeans and band t-shirts. I never deleted a picture because I looked fat. Every picture was a good one, only missing a cheesy quote.

I remember eating waffles with peanut butter for the first time in her kitchen after school, sitting at the bar top and pouring cold syrup over the warm waffles, cutting into the bread and watching the melted peanut butter fall onto the plate. It was magical. I had it every time I was at her house for almost a year after that. I don’t remember Tayler ever eating a waffle; I think her mother bought them just for me.

One day, at a middle school football game, Tayler and I ran into a few Spring Hill girls (a school only twenty or so minutes away from ours, and girls who were our arch enemies for unknown reasons). Three of them approached us and started boasting about how their school’s football team was going to beat ours. The yelling escalated and I, stupidly, started to insult their appearance. I called the girl closest to me a five-head. She glared at me with two different colored eyes, one a deep brown and the other forest green, and looked me up and down for a solid minute, studying me.

“Yeah, well, you’re fat,” she spat at me.

This didn’t start my eating disorder. Actually, I don’t remember it being particularly impactful. Tayler yelled at her, told her to shut up and leave, and oddly, she and the other two girls did. We sat in the school bleachers and laughed at them from afar. We laughed, but didn’t talk about what had happened. We never talked about bad things—unhappy things. I remember feeling a small sting right after she called me fat, but forgetting about it soon after. Tayler and I went and got salted pretzels with trans-fat filled cheese and watched our football team win the game. We stuck our tongues out at the three girls, sitting only a few bleachers away.

One year ago, and six years since my second trip to Hawaii, I tweeted that I was proud of myself for overcoming an eating disorder over seven years ago—that the worst of it was over. While I’m not completely free of its reign, I now wear a tiny crown with pride. A crown that says: I survived this, I’m alive and I have something to say about it. I cannot tell you how it started, but I can tell you how hard I fought it, how hard I sometimes still have to fight.

Tayler replied to this tweet with seven question marks. I replied back with eight. She was confused, and I didn’t entirely blame her. We had only seen each other three times in the two years that my weight fluctuated violently between one hundred forty-five pounds and ninety-eight pounds. We were close while texting but rarely in person. When she did see me at a fragile 98 pounds, her grin did not shrink, her questions did not come. She did not notice my dwindling body; she only cared that her friend had come to see her. She only saw me through Facebook pictures.

One picture is of me standing in my sister’s room, posted a few months before my second trip to Hawaii. I’m wearing a black Star Wars shirt, high-waisted purple shorts, and black Converse. My thighs are toothpicks and magnets that repel. My arms are twisted tree branches. My hair is paper. Tayler comments, “How did you get so tiny?!?!?!” I press like.

When I leave Hawaii for the second time, Tayler and I hug and wave goodbye. I watch the palm trees and clear, blue water disappear behind gray doors. I wear sweatpants because while it is 80 degrees here, it is below freezing back in Kansas. On the plane I turn on Mary-Kate and Ashley’s The Challenge, and watch them eat cat food and fruitcake. I refuse the peanuts that the flight attendant offers me, asking for only a water. I luckily have nobody sitting in the two seats next to me, so I sprawl out. I usually have a difficult time falling asleep on planes, but this time I fall into a dream state quickly.

It used to be common for me to have dreams about Her eating my brain. She is a dark shadow, no face but sharp teeth. She eats my brain slowly, devouring the hypothalamus of my forebrain first. She smiles at me after each bite, offers me a taste. I shake my head no, unable to speak, and She smiles wider. I never speak in these dreams. She smears blood down my cheeks.

I don’t remember if I dreamt of Her on this plane ride, but I probably did. She was in my dreams almost every night. I like to think that I dreamt about the first time I visited Tayler in Hawaii, when I ate peanut butter straight from the jar. When I posed in my bikini without Her yelling at me to suck in your stomach. When I slept in without regret.

When I wake up there is still an hour or so left of the flight. I am hungry but ignore it. My stomach growling sounds like applause. She is quiet. She has nothing to say to me quite yet. When I get off the plane She will remind me that I need to go to the gym. She will sing a song about how salad is my best friend. She will do this again and again and again. Every morning, every afternoon, and every night. She will not let me rest. I know.