The Graceless Haze

When I was young, I used to want to rip my heart out. Whenever Mother would get angry with me, she would say that I had a “graceless heart”¾a rather morbid insult for a young child. On the days she yelled at me, I used to cry so hard I forgot how to breathe and imagined that I could rip my heart out and grow a new one¾a kinder, redder, more graceful one.

My life on the farm was dull. The same soft creaking of the old house and the same old breeze that blew by was familiar in the worst way¾any twinge of nostalgia was riddled with disdain. The skies surrounding the farm were always the same shade of hazy blue. They never shone that brilliant, ocean-like shade of blue¾there was never any depth. It was always covered by a layer of haze as if I were seeing through the lens of an old film camera. I didn’t know any differently at the time, but I somehow felt the brilliance underneath like it was an invisible force whispering my name and promising me “more, more, more.”

My mother, Isadora, did everything in her power to make sure that I never craved anything other than that hazy blue that seemed to engulf everything around it. I almost never left the cottage that my great-grandfather had built. He’d left the house and the land surrounding it to my mother when he died. I was only a baby.

To my granddaughter, Isadora, he wrote in his will. It was scrawled in his perfect script that stayed immaculate until the day he died. I leave my house and my farm, so she may never want for anything.

My great-grandfather was an adamant farmer. I always remember seeing a photo of him on the wall in the kitchen where he was sitting on a tractor with a smile. He once owned one of the biggest farms in the state, using his acres of land to raise cattle and grow corn. Under my mother’s watch, the farm had dwindled to a mere half-acre of land, a garden, and the big red barn. I was in charge of caring for the animals in the barn (there was a goat, a pig, a cow, and a bunch of chickens), which I hated to no end. My mother refused to enter into the barn for some reason. Gathering eggs into a wicker basket before the sun comes up was certainly not my idea of fun, to my mother’s surprise. She did everything in her power to keep me from wanting more, which is why I was bound to the tiny oasis she’d created¾isolated from the world and its excess.

“Wanting more leads to sin, Florence,” she’d said one day when she was chastising me for asking to eat something else for breakfast. I was tired of the same old scrambled eggs and plain toast. I was thirteen at the time¾of course it was getting old. “Being unthankful is a sin.” Her voice was starting to get louder and louder, the way a train does when it gets closer to you. “Don’t have a graceless heart!”

But no matter how much she yelled at me or punished me, I was still that graceless girl with a graceless heart who didn’t want to eat those freshly scrambled eggs or sit underneath the hazy blue sky. I always found something to long for.

Every morning began the same clichéd way¾with the crow of the rooster. That meant I had about an hour before my mom was expecting a basket full of fresh eggs for breakfast. The sun would have just cracked the horizon, slowly turning from a soft pink to the blue I hated so much. The haze, the goddamn haze. It was relentless, or in my mother’s words, graceless. I always tried to get out of bed quietly, as to not disturb my cat who slept at the end of my bed.

I knew something was wrong when the rooster did not crow at daybreak. Rather, I awoke to the sudden jolt and shock of cold air caused by my mother ripping the quilt off of my body. I instinctively tried to yank the covering back, which certainly did not help my case against my already enraged mother. My eyes were still heavy with restless sleep.

“Florence!” she bellowed, eyebrows deeply lowered.

She looked distressed and sounded even more so. Her voice cracked when she uttered my name, and for a moment, I felt sorry for her. Sorry that despite her best efforts, I wasn’t happy. But that moment of tenderness was as fleeting as the spring, and the ever-present gnawing of disdain and resentment came to the forefront of my mind.

“The rooster didn’t crow,” I muttered, tugging at the sleeve of my gingham nightgown. No matter how angry I got, my default seemed to be timidity. I suppose that’s how my mother taught me.

“Get up, now!” she pursed her already thin lips, so they almost disappeared for a moment. “You have twenty minutes. Then, we will discuss repercussions.” She stomped out of my bedroom like a toddler throwing a tantrum. My cat was staring at me with his round blue eyes, confused by the racket. I pet the top of his head making him purr softly.

“Here’s to another day in the oasis,” I whispered. The words tasted bitter at the back of my throat.

I trudged my way out to the barn, tripping a few times over the hem of my nightgown. I hadn’t even bothered to change. It was later in the day, so the sky was already that shade of blue. The sun was warm, but the air was cold; almost unseasonably cold for the early fall. Nevertheless, I walked to the barn with my wicker basket in hand.

When I opened the doors to the barn, a rush of cold air hit me. The temperature was about twenty degrees colder than it was outside. I shivered but proceeded. I knew my mother would be expecting me in the next ten minutes. I started with the cow, pouring some feed into her trough. I had to milk her later since I was under a time constraint. I fed the goat and the pig the same thing and even stopped for a moment to pet them. The air got colder and colder the deeper into the barn I got, and by the time I reached the chicken coops, my entire body was covered in goosebumps. I scanned the area, searching for the rooster that had caused so much trouble. I didn’t see anything except the strange way all the chickens were huddled to one side, clucking wildly. My hand began to tremble, and I clutched the basket so hard I could feel the pattern of the weaving pressing into my hand. I knew it would leave red indents for a few minutes after I loosened my grip. Something wasn’t the same, and I would know, all I knew was the same. The closer and closer I got, the more evident it became that something¾god, I couldn’t put my finger on it¾was very, very wrong. Still I proceeded, stepping over the bales of hay that kept the chickens in that area, to collect the eggs.

One egg in the basket. A gust of wind blew cold air into my eyes. It made them tear up.

Two eggs in the basket. I heard breathing. I looked at the huddle of chickens. I knew that there was no way that an animal would breathe like that.

Three eggs in the basket. I heard chewing—really loud, ill-mannered chewing.

The fourth egg almost made its way to the basket, but before it could find its home among the others, I saw a figure hunched in the corner shoveling something into its mouth.

I dropped the egg and felt the yolk splatter on my ankle. The figure was human-like; I could see the outline of every vertebrae of the spine on its back. I tried not to make any sudden movements, but my breathing was uncontrollable.

The figure whipped its head around, throwing the long mess of tangled black hair in a rainbow motion. It looked up at me with murky eyes that showed signs of them once being blue. Its skin was so pale that it was almost purple; you could see its blood rushing through its body. The head was huge in comparison to the thin, willowy body that it was attached to. Its neck did not seem suited to uphold so much weight. Everything about its body read like a disproportionate drawing done by a child. The arms were just slightly too long, and the legs were a little too short. I stepped back, unable to break eye contact. The figure rose slowly to its feet as if not to startle me.

“You needn’t be afraid,” the monster said. The voice was a woman’s voice with an endless whisper. “My name is Delilah.” Her teeth were sharpened to a point¾every one of them. There was blood on them still, and I could smell the metallic scent wafting out of her open mouth. “I’m returning from a long journey. I must retain my strength before going home.” She circled me. Although she was walking on two legs, something about her gait made it seem like she was floating—flying. Her white dress was ripped and dirty at the ends, but clean on top.

“I can’t help you.” I turned to try to run away, but Delilah swiftly moved in front of me.

“Graceless girl!” she yelled in her whispery voice. She trailed my neck with a long fingernail. “I could slice you open right now.” She pressed her nail just hard enough to draw blood and let it drip onto her nail. She raised the drop to her lips and licked it off. “And my, my, wouldn’t you be delicious?” She cackled at the fear she saw in my eyes. She lowered her hand onto my shoulder. It was even colder than the temperature inside. I tilted my head down to hide my nose from the smell of blood and rotten flesh that continued to flow out of her mouth. Delilah grasped my face in both of her hands and brought it closer to meet hers. Our noses were touching. That scent was all I could smell. “You must help me. And I will make the world shine for you.”

“Wh¾wha¾ what do you need?” I barely squeezed those few words out. Delilah released my face and stepped back.

“Aha, I knew you would find your heart.” She made a noise that sounded like it was supposed to be a laugh but was more like an exasperated wheeze. “I need to feast. For five days. Every day, I need something fresh,” she grinned, exposing her pointy teeth, “to devour.”

She moved her skeletal hands rather theatrically.

I was momentarily mesmerized by the way her fingernails moved in a delayed wave as she gestured. The trickling of the blood from the cut on my chest snapped me out of it. I wiped it with the sleeve of my flannel, watching the deep red disappear among the pattern of the shirt.

“Well, we have a garden. I can bring you something from there.”

Deliah wheezed again. “No, child.” She moved close again. “I need a life!” All of her words were beginning to drag out more. “And I need blood!” She was so close to my ear that her breath made the side of my face burn. “There is always more.”

“Is there?” My gaze was still down, but Delilah raised my chin with the knuckle of her boney pointer finger.

“Un-bow your head, child.” She paused for a moment and took a breath. “I promise you,” she smiled. I wondered how her pointy teeth didn’t cut her lips. My mother used to tell me that one day I would cut mine on my sharp tongue. “There is more.”

I nodded and told her I would return the next day to give her something new to eat. I picked up a few eggs and put them in the basket as Delilah returned to the carcass.

For a moment, I looked forward to the next day. The hazy blue skies did not seem to haunt me.

Back at the house, my mother was stewing at the kitchen table. She cooked the eggs spitefully. I don’t know if it was the scent of the eggs or the thought that in only a few days things would go back to the way they always were that made my empty stomach lurch.

“Shall we pray?” my mother asked, already with her hands clasped together and elbows resting on either side of her plate. The steam from the eggs was fogging up her glasses. “Bow your head.” I dropped my neck but kept my eyes open. “Dear Lord,” she sighed. “Blessed be this meal that we are about to partake in. And let Florence remember what your word says¾‘God opposes the proud but shows favor to the humble.’ Forgive her. Amen.” She opened her eyes while her head was still bowed as if to avoid making any eye contact with me.

She chewed every bite of her breakfast slowly while staring at my plate. I stared back at her. I didn’t touch my breakfast, and she said nothing.

The first morning I woke up to silence was intoxicating. There was no rooster ringing in my ear singing the tune of rural prison bells. I pulled myself out of bed before the sun even dared to interrupt the stars. My cat, resting along my feet, looked up drowsily at me, his eyes shining through the darkness.

“Another day in the oasis,” I whispered in his direction as I pulled on one of my many long floral dresses that my mother had sewn by hand. I was doing everything as quietly as possible as not to wake my mother in the room across the hall. The thing is, whenever you’re trying to be quiet, everything seems ten times louder. The click of my boots against the hardwood floors sounded like an entire army and the creak of the front door felt like it echoed forever, but when I got outside, everything went silent. Not the sad kind of silence that made you feel alone, but rather the kind that meant you could fill it with whatever you wanted.

Delilah was waiting anxiously in the corner where I had found her. I caught a glimpse of the pile of dry bones next to her before she rushed to greet me.

“What shall I eat today?” She swirled around me once, rubbing her hands together ravenously.

I looked around the barn. It was just about feeding time and all the animals were already awake. Some of them wouldn’t be fed but become food for Delilah.

“You can eat the pig.”

Before I could even finish my sentence, Delilah had already made her way over to him. I looked away just before she impaled him, but not in time to cover my ears from the squeals.

The third day went the same.

I climbed out of bed before daybreak and headed to the barn to tend to Delilah. On that day, I let her eat the cow. My mother asked me why I didn’t bring any milk for the day.

“I’m tired of milk, Mother,” I said as I sat down to do my schoolwork. “Can’t you go into town so we can have juice or something?”

She did that thing where she tilts her head down and looks at me over her glasses instead of through them.

“Florence,” she sighed. “I pray that you talk to God and cleanse your heart of this ungrateful spirit of yours. I really do.”

I said nothing after that. And she did not speak to me for the rest of the day.

On the fourth day, Delilah finished off our animals when she ate the goat. It made me quite sad. He was a beautiful thing, with his black coat and perfectly spiraled horns, but he looked at me with a resolution that was almost comforting. If I didn’t know any better, I’d say he knew what was coming.

“My child,” Delilah began with a mouth full of goat flesh. I had become less squeamish about watching her eat. “What shall I eat tomorrow? On the final day.”

I looked around. I hadn’t thought of that. The barn was nothing but hay and bones at this point. Panic rose in my chest almost instantaneously.

“I¾I¾” I stuttered, trying to catch my breath that had suddenly run away from me. “I have no idea.” My voice trailed off. “There is nothing else.”

“You’re wrong, child.” She raised her head from the carcass only momentarily. “There is always more. You just have to search for it.”

I was distracted all day¾the only thing I could think about was Delilah. Every time I remembered that I needed to feed her on the last day, my heart started to race. Things came to a head when I was sitting at the table doing schoolwork my mother had given me for the day.

“Mother,” I began, glancing up from my schoolwork. I had been staring at the same unsolved math problem for the past ten minutes. “There is something I need to speak with you about.”

Whenever I spoke to her, my voice took on a very formal cadence. It wasn’t a conscious choice. I suppose my subconscious just knew that to ensure survival, I had to protect my mother’s idea of me.

My mother looked up from whatever she was crocheting.

“What is it, Florence?” She sighed with an already disappointed tone. She was getting tired of me, I could tell.

“There is something strange going on in the barn,” I was trying to make it seem as minuscule as possible. “Something very, very strange.”

She looked at me, her beady eyes cutting deep even beneath her thick wire glasses.

“And there is nothing more,” I got choked up on my own words. I could feel the tears welling up. “There is nothing more I can do about it.”

I don’t know what I expected from her, honestly. I knew it would not be sympathy or care or anything of that sort. Perhaps more of this shameful indifference she had recently adopted. Anything, but nothing prepared me for rage. She paused.

“Florence, you are testing my patience!” She slammed her crochet needles on the table so hard it made me jump. “Your thanklessness sickens me! You may not say it with your mouth, but you say it with your actions.”

“Mother, there’s something in that barn!” I yelled. I’d given up on trying to hold back my tears. They tasted bitter. “And I can’t make it go away!”

“Don’t you raise your voice at me!”

“Mom, please, listen!”

“I will not entertain your NONSENSE!”

I gulped.

“I did not raise you to be this way!”

“Mom, I’m sorry.” I was really crying then. My voice was cracking at every inflection. “I really am. I’m sorry that I can’t ever seem to obey the right way, and that I always seem to want more.”

She crossed her arms over her chest.

“I’m sorry! Please, forgive me! But I need you to listen to me!”

I was groveling at this point. There is truly nothing more shameful than having to beg.

“You make it difficult for me to be graceful,” she stood up and abruptly pushed her chair in. “And for that, I do not forgive you.”

She left me at the table, alone. Crying so hard I had to gasp for air.

The fifth morning of waking up without the crow of the rooster was not really waking up¾I hadn’t slept at all. The feeling of silence wasn’t as intoxicating anymore¾it was frightening. I stayed up all night trying to think of something for Delilah’s final day. I had considered going out and killing a squirrel. Or just begging her to eat something from the garden. But I wasn’t up to begging anymore.

I must have gotten too lost in my thoughts. The thing that snapped me out of my panic-induced haze was the sound of my mother opening her bedroom door and trudging her way to the bathroom. I whipped my head around toward the window. Sure enough, there were the early signs of daybreak. My heart instantly started to race. I wasn’t sure whether I was going to cry, vomit, or have a heart attack.

I jumped out of bed and began pacing around my room.

“There is nothing more, there is nothing more,” I repeated over and over again in my head. Or at least I thought it was in my head, but apparently, I was saying it out loud because my mother burst through my door.

“Florence, what in the world are you doing?”

My cat finally awoke from his sleep when she spoke.

I was so panicked¾nothing she said really registered in my brain¾I was just fixated on my cat. His orange fur and blue eyes and the way he still looked a little drowsy and a little confused. My heart sank to my feet when my brain registered my thoughts.

“Florence! Answer me!” my mother yelled. She was no longer hiding her rage.

I ignored her and made my way to the edge of my bed where my cat was. I snatched him into my arms and brushed past my mother toward the door.

“Florence!” she called after me.

Her voice trailed behind me as I broke into a stumbly run, seemingly unable to move my eyes anywhere but forward. I was headed to the barn barefoot against the cold grass.

I burst through the doors of the barn just as the sun was beginning to come up. I didn’t even realize how much I was freezing.

“Did you find anything?” Delilah approached so frantically; she was almost running on all fours.

“I couldn’t find anything. There is nothing more!” my voice was shaky. A few tears fell down my cheeks as I clutched my beloved cat to me. “This is all I have left.”

My cat looked curiously in Delilah’s direction. He was just as mesmerized by her fluid motions as I had been on the first day. She moved her hands slowly to watch the cat’s eyes follow her to the left, to the right, and then back again. Suddenly, she closed her hand and lifted her gaze simultaneously. She was glancing, no, glaring, right over my shoulder.

She smiled as she brought her focus back to me.

“Don’t cry, child.” she cooed, wiping my tears with the rough pads of her fingers. Her long fingernails scraped my cheeks. “There is always more.”

I shook my head and brought my gaze to the ground. “There’s nothing. I’m sorry.”

She placed the back of her hand under my chin and raised my head.

“Florence, my child,” Delilah breathed. “There is always more.” She looked at me with knowingness in her eyes, as if she was trying to send her thoughts rushing through my brain. “There is always more.”

She motioned behind me with one of her skeletal hands.

There was my mother standing in front of the open doors. The way the early morning light was hitting her, she looked like a shadowy figure. I could only see her silhouette, yet I could imagine her facial expression: a distant stare with flickers of fear. She didn’t dare to move from her place, not to leave or to escape from Delilah’s beckoning. This was the one and only time I witnessed her speechless.

Delilah placed a hand on my bare shoulder. It wasn’t as cold as it was the first day¾there was a humanlike warmth that permeated my arm. When my own eyes sparkled with understanding, Delilah brushed past me without hesitation.

More, more, MORE, I thought. It wasn’t a quiet thought this time, instead my mind screamed every syllable.

Delilah floated over to where my mother was and circled her once. The hem of her tattered dress followed a few seconds behind. I wish I could have seen my mother’s face. Would I have detested the fear in her eyes or savored it? I suppose I’m lucky that I didn’t see her face; that I didn’t have to learn of my own cruelty on that day.

Delilah sliced her chest open with a single swift motion. I could hear a slight sputter, but I was surprised not to hear the gush of blood and a loud cry.

I didn’t know that death was so silent.

I saw Delilah’s hand disappear, stretching the cut down my mother’s chest into a chasm. She grasped my mother’s still-beating heart out of its rightful place, the arteries rebounding and spraying drops of blood on my face. I didn’t bother to wipe them away. My mother’s heart beat three more times before it went still.

Th-thump. More.

Th-thump. More.

Th-thump. More.

Stillness. Everything.

A sick smile broke across my face as I relished in the feeling of that soft haze fading from the sky. I knew the brilliance would be revealed to me in only moments more.

________________________

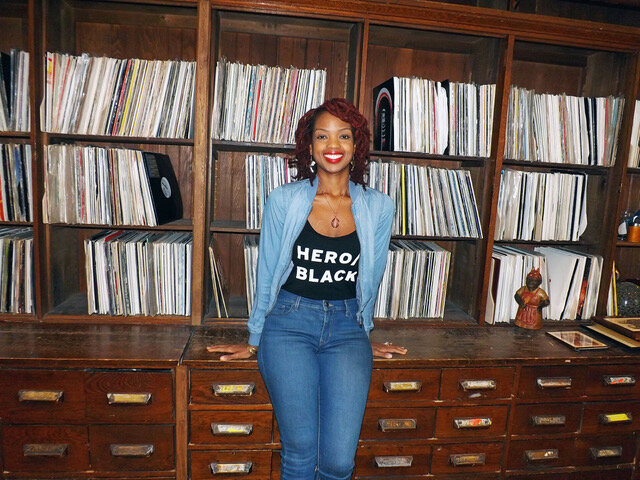

Deanna Whitlow is a fiction undergraduate at Columbia College Chicago. She was a staff writer of the digital publication Affinity Magazine; and she founded SameFaces Collective, an online literary and art magazine where she is both editor and a regular contributor.