Behind Closed Doors

Chelsea and I take our spots behind the long trail of women waiting in line for the bathroom. The girl in front of us is crying, her mascara leaving black streaks down her cheeks, while her friend rubs the small of her back, telling her, “It’s okay. She’s not even as pretty as you anyways.”

I’m watching this when Chelsea reaches out a manicured finger to my head. She twirls a strand of my curly red hair around her finger, and gently pulls until the tension causes it to straighten. Then she lets go, and the corners of her lips turn up in an amused smile, as she watches it spring back into its original curl shape.

“Your hair is fun,” she says.

I give her a tight smile and we move up with the rest of the line. When we finally move up far enough to be inside the bathroom, the loud trap music blaring in the club muffles. I can’t make out what Gucci Mane is rapping about anymore, but I can still feel the bass pounding through my bones.

“I have a surprise for you,” Chelsea says. She reaches a hand down the front of her faux leather miniskirt, and I dart my eyes around to make sure no one is watching.

“What are you doing?” I hiss, taking a step forward to block her from people’s view.

She digs around for another moment before pulling out a tiny plastic bag with two little pink pills inside of it that match the color of her lips. Her face lights up as she holds it in front of her stomach for me to see.

“Where did you just pull that out of?” I ask her.

“My panty pocket,” she replies matter-of-factly. “That’s what they’re there for.”

I know exactly which pocket she’s talking about. I highly doubt that the small extra flap of cotton sewn into the crotch of most panties was designed as a pocket for girls to place drugs in order to sneak into clubs. I have to admit that it’s a pretty great idea to use it as one.

“What is it?” I ask.

“Ecstasy,” she replies.

I don’t want to admit it to her, but I’ve never tried ecstasy before. In fact, I’ve never tried any drug other than weed before, and I’m not sure that I want to tonight. I’m already feeling pretty tipsy. I don’t want to push myself over the edge.

“I can’t,” I tell her.

“Why not?” she asks. We take a few baby steps forward.

“I have work tomorrow.” This isn’t a lie. I do have work. Not until three in the afternoon, but she doesn’t need to know that.

“So?” A toilet flushes, and the girl who’d been crying walks out. She gasps at herself in the mirror, and quickly dabs under her eyes with a piece of paper towel that she rips from the dispenser.

Chelsea goes into the now-empty stall and when another toilet flushes, I go into that one, hoping that Chelsea will just drop this whole ecstasy thing. When I come out, Chelsea is standing at one of the sinks washing her hands, her eyes meeting mine in the reflection of the mirror. I go up to the sink next to her, taking in my own reflection.

My cheeks are a flushed, bright pink, and there are a few tiny flecks of black under my eyes where my mascara has begun to flake, but my mauve lipstick hasn’t smudged, and what little cleavage I have looks great in my dress. I usually don’t wear dresses like this one—sequined, short, deep-V neckline—but when Ian told me that we were going to a club, I knew I had to find something other than the white cotton sundress I’d worn for my high school graduation.

I bought this one on sale at Charlotte Russe earlier tonight. My very first club dress. As I sat on the train going into the city, I noticed a few men checking me out and a few women shooting me angry glares. I pressed my lips together, pretending not to notice, but inside, my heart was pounding.

“It’s only one pill,” Chelsea continues to my dismay. “You’ll be fine to go to work tomorrow.”

I sigh, tossing the idea around in my head. “What about the guys?” I ask. I’d come here with Ian after all, and had just met Chelsea and her boyfriend Marco for the first time tonight. It didn’t feel right doing drugs with one of Ian’s friends behind his back like this.

“What about them?” she chuckles, turning off the sink and shaking water off of her hands. “My weed guy gifted me these for free last weekend, and I figured tonight would be the perfect time to do them.”

“Wouldn’t you rather do them with Marco, though?” I ask her, following her out of the bathroom and back into the club.

“Marco’s always getting fucked up without me,” she shouts over her shoulder at me. “I want you to have it.”

I follow her up to the bar where she orders two double Jameson’s and ginger ales, passing them both back to me. She takes the little baggy out of her clutch, opens it underneath the bar, and drops two pills onto the palm of her hand, letting the baggie fall to the slightly sticky floor when she’s done.

“Here,” she says, holding her hand out to me. I stare at the pink, button-like pills that seem to glow in the dim, shadowy nightclub. “Come on. It’ll be fun. I promise.”

Sighing, I hand her drink back to her and take a pill. She grins widely at me, and we both toss the ecstasy back with a sip of what’s mostly Jameson, before I give myself enough time to think up another excuse not to.

“Okay, now let’s go find the guys,” she says. She grabs my clammy hand and leads me into the sea of sweating, gyrating bodies.

I don’t remember leaving the club, but we’re outside now on a street I don’t recognize. A breeze whips through my hair and I shiver, but I don’t feel cold. I should feel cold, shouldn’t I? Instead, I feel warm and fuzzy like freshly spun cotton candy.

I hear a click and follow the sound to see Marco with a Camel Crush hanging out of his chapped lips, one hand forming a roof over the top of it, the other wrapped around a lighter. He attempts to light it, but the wind keeps blowing it out.

“Fuck,” he murmurs around the cigarette.

“How do you feel?” Chelsea is standing in front of me now, her lips the color of bubblegum, pupils the size of saucers, and pores large and visible under the harsh white streetlight.

“Good,” I say. And I do feel good.

She grins a toothy grin and says, “Give me your arm.”

I hold my arm out to her and she gently runs the tips of her coffin-shaped nails up and down my skin, causing it to prickle with goosebumps. I feel myself smile and realize how badly my jaw aches.

“Hey, give me a cigarette.” Chelsea has moved away from me now, toward Marco. Where’s Ian?

A shudder of panic runs down my spine, and I look left and then right, but only see a cluster of people smoking and a girl in a hot pink dress drunkenly shouting into her cell phone. Did we leave him at the club? My heart rate quickens for a moment, but then I see him emerging from the nearby alley, pulling the zipper of his jeans up as he approaches us. His t-shirt rides up a little bit, revealing a tan strip of stomach. Both he and Marco are wearing t-shirts and dark jeans with jackets (Marco’s leather, Ian’s a bomber). They have a way of making t-shirts and jeans look polished, expensive.

“You ready to go?” I turn my head toward the sound of Chelsea’s throaty voice. “The Uber is two minutes away,” she says.

Chelsea wraps a thin arm around me, passing me her half-smoked cigarette, and Ian walks over to where Marco stands, the cigarette in his mouth finally lit. I don’t normally smoke, but I take a puff, coughing as it burns the back of my throat. I pass it back to her and she takes a long drag before stomping it out with the toe of one of her black strappy pumps.

A shiny black Nissan Altima pulls up and we all pile inside; Marco sits up front and I sit in the back, smushed between Chelsea and Ian. The smell of whatever woody cologne our driver drenched himself in is overpowering inside the tight confinement of the car, and I reach over Chelsea to roll down the window.

“Hey, you can’t smoke that in here,” the Uber driver says to Marco in a thick Indian accent.

I realize that Marco still has a cigarette between his lips, smoked down to just a nub now. Chelsea laughs through her nose next to me. “My bad,” Marco says, rolling down the window and tossing it out.

I watch the Uber driver roll his eyes in the rearview mirror. “You’re going to Justine Street?” he asks.

“Yeah,” Marco replies.

We pull into the street and begin driving, the wind tousling my hair through the open window. Marco starts fiddling with the radio, asks the Uber driver if he has an aux cord (he doesn’t), and turns the volume up to twenty when he finds 107.5 playing a rap song that I vaguely remember hearing earlier in the club. I can tell the Uber driver hates passengers like Marco by how tightly his hands are gripping the steering wheel and how erect his posture is.

“Where are we going?” I whisper to Ian.

“A friend’s house,” Chelsea answers for him. “My weed guy.” She winks at me, as if this is code for something that only her and I know about, and I wonder if Ian and Marco know that she and I are on ecstasy. I can’t remember telling them we were.

I remember finishing that drink she and I got from the bar. I remember finding Ian and Marco deep inside the crowd, where I couldn’t tell whether it was my sweat, someone else’s, or a mixture of the two, dampening my dress so that it stuck to my back. I remember dancing. A lot. So much that the muscles in my thighs ached. I remember Marco and Chelsea whispering to each other. Maybe she told him about the ecstasy then? I remember Ian and Marco leaving to go grab more drinks, Chelsea grinding her body against mine while they were gone. How her body seemed to send mine some kind of electric charge as it rubbed up against me. Then that’s it. It’s as if we time-traveled from the club to the street, and into an Uber.

“Are we picking up weed or something?” I ask.

The Uber driver glares at me through the rearview mirror, and I remember that he’s within earshot of me.

“Something like that,” Chelsea replies. I glance over at Ian, who’s staring out the window, and I wonder why he’s being so quiet today.

He and I met through Tinder, something none of my friends back home in Glen Ellyn know I’m on. People tend to be very judgmental where I’m from. If my friends knew I’d met a guy on Tinder and then hopped on a Metra train out to the city to see him a few days later, they’d think I was insane. I’d be lying if I said that it wasn’t exciting though, having this secret life that no one but I knew about. Where I’m from, everyone is content with being content. Their idea of fun is going to a movie or to the mall. It gets pretty old after a while. I wanted to meet new people. I didn’t expect to meet someone so soon.

The first time Ian and I met, he took me out to lunch and we walked around Lincoln Park Zoo. While we were waiting for the Uber that he called to take me back to Ogilvie Station, he leaned over and kissed me. His stubble was prickly against my chin and his lips tasted like nicotine. I’d never kissed a guy who smoked cigarettes before, but I didn’t mind the taste. I kind of liked it, actually. He had been so sweet and funny and talkative that day, but now he won’t even look at me. Did I do something wrong? Had I done something embarrassing in the stretch of time that’s somehow escaped my memory?

I try to shake off this thought, deciding that he’s probably just tired, and stare out the window. As we continue to drive, the tall buildings and overflowing bars turn into three-story apartments and tiny corner stores with metal bars on the windows. An uneasy feeling settles in the pit of my stomach.

“Where does your weed guy live?” I murmur to Chelsea.

“Don’t worry. We’re almost there,” she replies.

When the Uber comes to a stop, it’s in front of a white two-story house with chipped paint and a miniscule concrete porch. It sits on a patch of dead grass, enclosed inside a metal gate. All the curtains are drawn, and the porch light is off.

“Thanks,” Marco says to the driver as he gets out of the car. Ian and Chelsea open their doors to get out too, but I remain frozen in my seat, staring out Ian’s open car door at the house.

Chelsea walks around to Ian’s side and bends down to peek in at me. “Come on,” she says.

I glance back at the Uber driver, who is watching me through the rearview mirror, his thick black eyebrows knitted together. I feel a sudden overwhelming urge to ask him to take me away from here. Away from this house, this neighborhood, this city.

I think about my room back home in Glen Ellyn. About the pink and white bedding I’ve had since I was sixteen and the big window looking out into the front yard. I think about my mom and dad. They’re probably sitting on the couch right now—my mom with her legs tucked underneath her and the quilted blanket she loves draped over her, and my dad in his favorite Blackhawks sweatshirt with his arm resting on the back of the couch. Neither are worried about me because they think I’m spending the night at Kaitlin’s house, only ten minutes away, just right down Roosevelt Road.

“Leah,” Chelsea says, sounding slightly irritated now.

I tentatively slide across the smooth leather seat and step out into the night, which feels much colder now. Chelsea shuts the door behind me, and I watch the taillights of the Nissan get smaller and smaller as it speeds off down the street, eventually making a right, and disappearing around the corner.

Ian and Marco are already waiting on the tiny slab of concrete porch, and as Chelsea and I ascend the three brittle stairs that lead up to it, the front door opens. A tall, wide Hispanic man fills the door frame, yellow light pouring out of the spaces his body does not take up.

His murky brown eyes land on me and the corner of his mouth curls up ever so slightly. He greets Ian and Marco, and they both slide past him into the house. When Chelsea approaches him, he wraps her up in a hug, and I watch his large, tan hand travel down to her ass. My breath quickens.

“And who might you be?” he says to me, his voice deep and gravelly. He looks me up and down, and I suddenly wish that my dress was a few inches longer, the neckline a few inches higher.

“That’s Leah,” Chelsea introduces me. “Leah, this is Damian.”

He holds a meaty hand out to me, the same hand that was just on Chelsea’s ass. I reach out my own trembling hand and shake it, his palm warm and calloused.

“Come on in,” he says to us. I trail behind Chelsea into the front hallway, pressing the door shut behind me. His house smells like weed and disinfectant, skunky and astringent.

We walk past the kitchen where a woman not much older than me sits, rolling joints. She looks up at me as we pass, her cold, empty eyes meeting mine for only a moment before returning to the pile of weed in front of her.

When we walk into the living room, Marco and Ian are already sitting down, Ian on the faded tan couch and Marco on one of the two metal folding chairs adjacent to it. Damian sits down on the other one, and Chelsea and I sink down into the worn couch, with me winding up between her and Ian again.

The only other furniture in the room is the knotted wood coffee table (scattered with two full ash trays, random blunts and nugs of weed, a small scale, even smaller baggies, and a remote) and the TV, which sits on a fold-out table parallel to the couch. I feel very out of place here in my black sequined mini dress and three-inch red heels.

“So,” Damian begins, his voice booming throughout the small rectangular room. “Anybody need a drink?”

“I thought you’d never ask,” Chelsea replies. She rises from her spot on the couch and looks down at me. “Come on,” she says. “Let’s go help him grab the drinks.”

I glance at Ian who is sunken back into the couch, too busy picking at his cuticles to notice that I’m looking at him. Tentatively, I rise from my seat and Chelsea takes my hand in hers. She follows Damian into the kitchen, pulling me along behind her, but I don’t think it takes three people to go grab some drinks.

My hand is slick with sweat when Chelsea finally releases it. The woman at the table glances up at us, her face remaining expressionless. Damian places his hand on the back of her chair, leaning down to murmur something into her ear in Spanish. She looks back up at Chelsea and I, then gets up and walks out of the room.

“Come on, ladies,” Damian says to us. We follow him over to the refrigerator. “So how did you like those pills?” he asks as he opens the door to the fridge. White light pours over his tan face. I notice a bright pink scar that snakes around his left eye, beginning above his eyebrow and ending at the top of his cheek.

“They were great as always,” Chelsea purrs. “Leah, what did you think?”

My heart rate quickens at the sound of my name. Damian pulls out a six-pack of A Little Sumpin’ Sumpin’, and he and Chelsea both look at me, waiting for my answer. “They were great,” I parrot Chelsea, my voice shaky as it leaves my mouth.

“I have more of them upstairs in my room,” he says. “You want another one?”

He and Chelsea look to me again as if they’re counting on me to give them the correct answer. Instead, I stand there, mouth slightly ajar, wondering if Ian and Marco are wondering why it’s taking us so long.

“She wants another one,” Chelsea answers for me, her bubblegum lips coiling up into an impish smile. She takes my hand again and as Damian begins leading us out of the kitchen, beer still in hand, I feel the pad of her thumb gently begin to stroke the top of mine.

Ian and Marco don’t even glance up at us when we pass by the living room. A thick cloud of smoke hangs around Marco’s head, and he reaches through it to pass Ian a bowl, as we continue past them to the stairs.

The stairway leading to the second level of Damian’s house is dim and narrow. Each stair creaks under our weight and the closer we get to the top of them, the more I want to turn around and run out of here. My gut is playing tug-of-war with itself inside my stomach and a cold sweat has broken out on the back of my neck. All of the doors upstairs are closed, but Damian opens up the second one to the right, and we file inside. He closes it behind us.

Inside Damian’s room is a mattress with disheveled blankets and sheets, a nightstand, and a dresser with a TV that sits on top of it. The only source of light in the room comes from a small lamp that sits on top of his nightstand, casting a dim, yellow glow over everything. I notice a rosary with turquoise beads sitting on the nightstand too. The silver cross hanging from it gleams under the light from the lamp. The miniature Jesus hanging on it unnerves me.

Damian plops down on the mattress, placing the six-pack on the carpet at his feet, and opens the drawer to his nightstand. Chelsea sits down beside him. I stand over them, feeling awkward and slightly nauseous.

“Sit down,” Chelsea tells me, tugging on my hand.

I sink into the bed next to her. Damian pulls out a Ziploc baggy full of those pink little pills, which have a slightly orange hue to them under the yellow light of the lamp, and hands one to me and one to Chelsea. Next, he pulls out two beers and opens them each before passing them down to Chelsea and me.

As I pop the pill in my mouth, I notice that Damian doesn’t take one. But he grins at me as I swallow mine down, and I think I can feel that little pink pill land in the pit of my stomach, which groans. I realize that I haven’t eaten anything since lunch. My mom would have a fit if she knew that. She was always so persistent on making sure that everyone had enough to eat.

I wonder what she and my dad had for dinner tonight. It’s Friday so they probably had Lou Malnati’s. Every Friday since I can remember, we would order a deep-dish cheese pizza from Lou Malnati’s for dinner. When I was little, I’d always go with my dad to pick it up, and when we rode home, I’d place the pizza box on my lap, holding it steady so that the cheese wouldn’t slide around when my dad turned a corner. I hope the cheese didn’t slide now that I wasn’t there to hold it.

“God, these heels are killing me,” Chelsea says. She kicks them off, then looks to me. “You should take yours off, too. I’m sure your feet are sore from dancing all night.”

They are sore, but I don’t want to take my shoes off here. If I take them off, that means we’re staying awhile, and I don’t want to stay awhile.

“Shouldn’t we head back downstairs?” I say instead. “Won’t the guys be wondering where we are?”

Chelsea rolls her eyes dramatically and leans back on her elbows, removing the barrier between Damian and I. “Didn’t I tell you earlier not to worry about the guys?” She reaches a bare foot over and kicks the shoe off my right foot for me.

I glance at Damian, who sips a beer, his dark eyes peering over the top of it at me. I feel Chelsea kick my other shoe off, and I think I should make up an excuse to leave soon. Say I have to get some rest before work in the morning or something. Then I can call an Uber and go home. I could be back in my room watching Netflix in less than an hour. I should tell them I have to leave. I should get up and go back downstairs, but my limbs feel heavy, too heavy to move, so I remain frozen on Damian’s bed, my spine stiff and straight.

“What’s wrong with you?” Chelsea asks, moving her hand, cool and damp from holding the beer, so that it rests on top of mine. “You were having fun earlier, weren’t you?”

That was back when we were at the club, I want to say. Before we came here.

“Yeah,” I say instead.

“Well relax, and let’s keep having fun then,” she replies, her lips curling up into a jack-o-lantern-like grin.

“Yeah,” Damian chimes in. “You want some music? I can put on music.”

He rises from the bed and walks over to a closet. I glance to my left as if I may find a way out of this over there, but all I see is a framed photo of a baby with pink pudgy cheeks and a blue knit cap on his round head, sitting on the dresser. I wonder if this is Damian’s child. It must be. Why else would he have his picture out on display in his bedroom? Is that woman from downstairs the mother?

Damian walks over to the dresser and places a portable speaker on top of it.

“I just don’t get why we’re listening to music up here while Ian and Marco are sitting downstairs,” I say.

Chelsea sits back up, her face cast over as she glares at me. “Here.” She picks up my beer, which I’d set down on the carpet, and shoves it at me. “Drink this and we’ll get the music going and we’ll all have fun, okay?”

I stare at the bottle, watching a single drop of condensation roll down the side of it like a tear rolling down a cheek. I let out a deep sigh and take it from her, swallowing down a long sip.

She smiles and says, “Good girl,” as glitchy electronic music begins playing from the speaker. Then she stands up, holding out a hand to me. “Dance with me.”

I stare at her hand for a moment before I hesitantly take it, her thin fingers interlacing with mine, and let her pull me up off of the bed. I take another long swig of my beer before setting it down on Damian’s nightstand.

Chelsea twirls me around like they do on that show my mom loves, Dancing with the Stars, and I feel like this ecstasy pill is hitting me quicker than the last one did.

Electricity runs up through my fingertips, spreading throughout the rest of my body. Damian turns the volume on the speaker up and Chelsea’s blonde hair whips around as she dances, moving her hips and head in sync with the music. I get that feathery feeling just underneath my skin and when Chelsea pulls me toward her. I let her. When her bubblegum lips meet mine, I don’t pull away, even when her cold, wet tongue slips between my lips and into my mouth.

I’ve never kissed a girl before. It’s different than kissing a guy. Softer. Sweeter. Gentler.

I feel her hand tangle up in my hair, her fingers gently beginning to knead the back of my head.

When we fall onto the bed, I notice that the hem of my dress has hiked up to the top of my thigh. I reach a hand down to fix it, but Chelsea reaches a hand down to stop me. Then I feel that same hand begin to travel slowly up my thigh and under my dress, and when it reaches inside my panties, I let my arm fall limp at my side, my back tensing up in pleasure.

I don’t know how much time passes by. An hour? Twenty minutes? Five? It all becomes fuzzy once the ecstasy peaks. But at some point, once both of our clothes have been shed (I hardly remember taking mine off), I catch a glimpse of Damian out of the corner of my eye and my stomach lurches. I forgot he was even in the room, but there he stands, off to the side of the bed, lips sneered and shoulders squared, holding his phone out, recording us.

I immediately jerk upright, my head swimming as I do so.

“What’s the matter?” Chelsea asks me. I stare, wide-eyed at Damian, and he looks back at me, something smug and sinister flickering in his eyes. He doesn’t put the phone down.

I tear my eyes away from him and hold my arm up across my bare chest, feeling trembly and disoriented as I turn my head left and right, searching for my dress. Chelsea glances back at him, but doesn’t seem even vaguely phased.

“Sweetie, relax,” she tells me, placing a cold hand on my shoulder. “Nobody you know is gonna see this.”

I stare into her calm, dilated eyes. “What the fuck are you talking about?” I remark, jerking my shoulder so that her hand falls off of it. The ecstasy is taking a turn now, and I feel as though I might throw up. I squeeze my eyes shut, taking in deep, measured breaths through my nose, and letting them out slowly through my mouth.

Chelsea sighs as if me not being okay with all of this is inconvenient for her. “Damian’s family back in Colombia sells them for us, so no one in this continent will ever see them. You’d be surprised how much people will pay for some real-life amateur American porn.”

Porn. The word is so alien to me. I’ve never even watched porn before. An acidic taste creeps up the back of my throat.

I stare at her, waiting for her to tell me that she’s just kidding, that of course this hadn’t been the plan the entire night. I remember Ian and Marco downstairs. Were they in on this? I wait for her to tell me they weren’t in on this, that at least Ian wasn’t. But she just stares right back at me impatiently with pursed lips.

“I need to leave,” I say, sliding past her and finding my dress crumpled up on the floor next to the bed.

Chelsea sits there, looking irritated. “Why? We were having fun. Just forget he’s even there.”

I step into my dress, knowing in that instant that I will never wear it again, and as I inch it up over my body, I notice that Damian is still recording. Why the fuck is he still recording?

“Leah, come on,” Chelsea says from the bed.

My throat burns with unshed tears, and I reach around my back to zip my dress up, but my hands are shaking and I’m only able to get it up halfway, so I just leave it, grab my shoes, and walk out of the room.

I float down the stairs, the sitcom audience laughter from the living room TV growing louder as I near the bottom. When I stop in the doorway to the living room, Ian and Marco both look at me. I wait for them to gasp, to ask me what happened, but they just sit there smoking their cigarettes, looking stoned and bored.

My legs are like Jell-O as I walk over to the couch to grab my purse, keeping my head cast down, refusing to look at Ian or Marco as tears well behind my eyes and humiliation burns my cheeks. I just want to get out of here, away from these people. I just want to go home.

-

Where my mom has probably fallen asleep on the couch during whatever movie my parents were watching. Where my dad has probably woken her up ever so gently and followed her upstairs to bed, leaving the light above the sink in the kitchen on for me in case I change my mind about staying at Kaitlyn’s, and so I wouldn’t come inside to a pitch dark house.

Home feels different now. Maybe home isn’t where I want to go after all.

“I wouldn’t go out there alone if I were you,” Ian says as I turn to leave. “Just sit down and relax. I’ll call you an Uber.”

I’m really fucking sick of people telling me to relax, but I sit down anyway, leaving a large space between Ian and I.

I squeeze my eyes shut, flashbacks of Chelsea and Damian playing behind my eyelids. Her lips, bubblegum pink, coming toward mine. Her hands, cold and soft as they traveled expertly up and down my body. And then Damian. Sneering. Foreboding. Recording. People are going to see that. People are going to see me. I repeat it over and over again in my head, trying to make it feel real. I know Chelsea said no one on this continent would ever see it, but how could I trust her after everything she’s done? What if she was lying? What if someone I know sees? What if my dad sees?

When I open my eyes, they’re blurry with tears.

This is all Ian’s fault. He was the one who messaged me, who took me out and made me laugh. Who brought me here. Or maybe it’s my fault for being stupid enough to trust some guy I met on Tinder. Is this my fault?

I think about that day at Lincoln Park Zoo and how I stumbled over what to say because I was so nervous around Ian. I think about the second time we hung out, eating pizza and watching movies in his studio apartment. I let his hand travel up underneath my shirt while we made out on his futon. I decided then and there that the next time we hung out, I wouldn’t stop him if he tried to have sex with me. What an idiot I was. I should have known that Ian didn’t actually like me. Ian, with his cool friends and cool city apartment and cool apathetic demeanor, would never be into me, sweet little Leah from Glen Ellyn. I should’ve known to take his attraction to me with a grain of salt.

Six minutes later, my Uber arrives. Neither Chelsea nor Damian come downstairs in those six minutes. Neither Ian nor Marco say a word. They just sit there, smoking and watching TV, as if all of this is perfectly normal to them. And maybe it is. The thought makes me queasy, and I’m grateful when Ian finally utters the words, “He’s here.”

When I get into the Uber, I realize it’s the same driver who dropped us off here. He looks at me in the rearview mirror, sitting there with my dress half unzipped and my shoes on my lap and tears staining my cheeks.

“Going back to Glen Ellyn?” he asks.

“Yeah,” I croak, and he peels off down the street.

_______________________

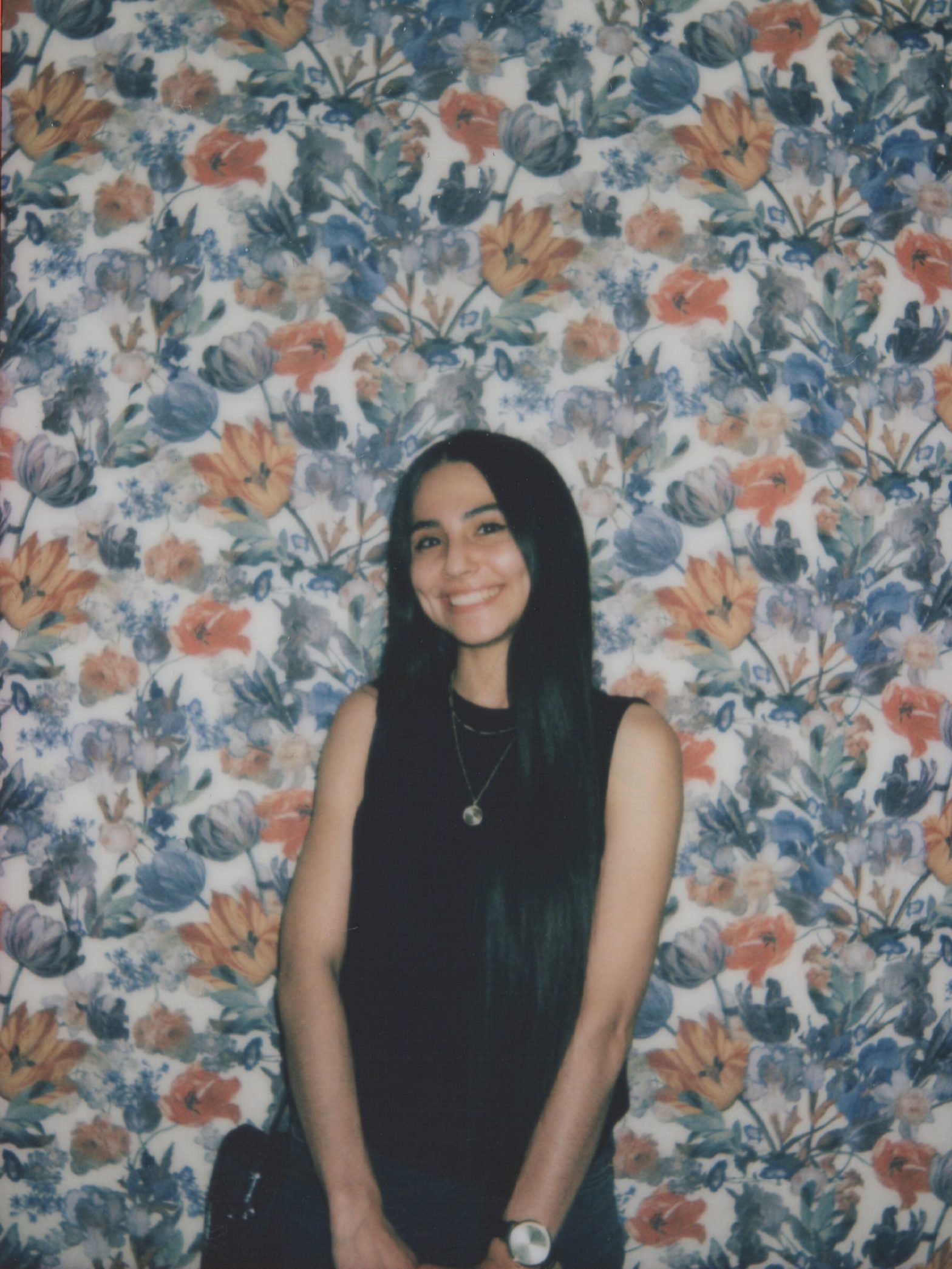

Alexis Bowe graduated from Columbia College Chicago with a double major in creative writing and graphic design in the fall of 2018. Since graduating, she has done some freelance writing, as well as continued to work on her novel-in-progress. She is an emerging writer, and her work can be found in Hair Trigger 2.0 and Hypertext Magazine.