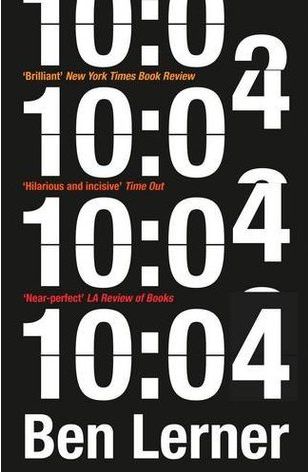

10:04

By Cody Lee, Reviews Editor

The Upper-Middle-Class White Man has spoken, and god, I can read his prose book and book again. Let me explain that there is nothing unique about this story (a thirty-three-year-old writer slugs around N.Y.C., writing things, getting drunk, and overanalyzing his thoughts). It’s essentially a tale that the fellow walking down Michigan Avenue might explain over a glass of Glenfiddich 15. However, that’s what makes 10:04 by Ben Lerner golden, and furthermore, human; the colloquial tone intertwined with Lerner’s poetic (sometimes, perhaps, pretentious) language leads the reader into a bittersweet tunnel of intrauterine insemination, Ketamine, and New Yorker articles, all during an assumed apocalyptic countdown.

Although the novel’s only 241 pages, Lerner is able to squeeze a myriad of information into the text (e.g. his love of cooked baby octopi, the process in which instant coffee becomes packaged, the little pre-piss dip and lift that men do when pulling out their own package), but above all, Lerner discusses the omnipotent deity: The Dollar Bill. 10:04 reads as a nagging mother with nil more than money on her mind, which can be upsetting, but all Mom’s trying to do is prepare the reader for the real world. Perusing the book as a college student (in a liberal arts school, especially), one might become quite frustrated while listening to the narrator brag about his “strong six-figure” advance, but realistically, who wouldn’t boast a bit if they received two full-year salaries for one unfinished novel? As annoying as the money-talk seemed sometimes, I wanted more, more, more because not many (fiction) authors seem to supply such data. In 10:04, Lerner points out that an article in the New Yorker pays approximately $8,000. No one wants to say how much they’re paid . . . I would thoroughly enjoy sitting in a small white room, directly across from Ben Lerner while he spits out number after number in relation to the writing community. As dull as digits seem to writers, I can speak for myself—and probably a few others—when I say that, as a twenty-two-year-old African-American “kidult” with hundreds of thousands of dollars in debt, it’s definitely a dream of mine to live like an upper-middle-class white man, and talk about my funds (acquired via publications, stipends, etc.) for hours on end.

The story bounces back and forth in this meta I’m-writing-a-novel-that’s-super-similar-to-my-actual-life first-to-third-person mashup, which works surprisingly well in its subtlety for the first few switches, but once it grows obvious that the narrator’s basically narrating himself, the point-of-view seesaw becomes cute, but not much more.

What I find delightful about 10:04 is the narrator’s disgust of the art world in which he’s involved fused together with his obvious knowledge that he himself is indeed associated with the bourgeoisie, and not just some ghost, hovering over the masses and laughing at their idiocies (although, one could argue that the middle class does hover over the masses, but typically avoids laughing because laughing at people is uncivilized and an example of improper etiquette). This becomes apparent when the narrator’s at dinner with a few acquaintances—mostly distinguished writers or English professors—and he observes “the distinguished male author” spaz out (in Spanish) on the busboy who poured him still water instead of sparkling. Directly after, when the narrator’s water is poured, he’s unsure whether to thank the worker in English or Spanish . . . clearly, the narrator has never worked any sort of service position, because anyone who has knows that a simple “thank you” will suffice.

I can’t help but think of Lerner’s (page-and-a-half) reference to Walt Whitman: the self-proclaimed Everyman, although apparently not, since he was Walt Whitman and all . . . I wouldn’t go as far as to say that Lerner’s the neo-Whitman, but the arrogance, married with the pedestrian-esque blanket that’s thrown over the arrogance (not to mention the eroticism) definitely allows my mind to imagine a bloodline connecting the two; one drop counts, check history textbooks.

10:04 does exactly what a novel is supposed to do: it takes the reader out of their own unexceptional life, and transfers them into the shoes of someone else. However, this “someone else” happens to be just as ordinary as the reader, thus relatable, thus automatically okay. This is in regards to the content, now add money that I don’t have but would love to learn to obtain, and sprinkle in a layer of poetics (all novels aside, Ben Lerner is a poet), and out comes 10:04: an intelligent look into the brains of the bifocaled souls on train rides home, or rather, you, me, and everyone else with hopes of living as The Upper-Middle-Class White Man, the Everyman.

Similar works:

Literature: Book of Numbers by Joshua Cohen

Film: Seeking a Friend for the End of the World directed by Lorene Scafaria

Etc.: “there’s too much blood in the attic today” by happy jawbone family band

Cody Lee has no sense of humor, and hates everyone. He’s smart, too.

January 02, 2017