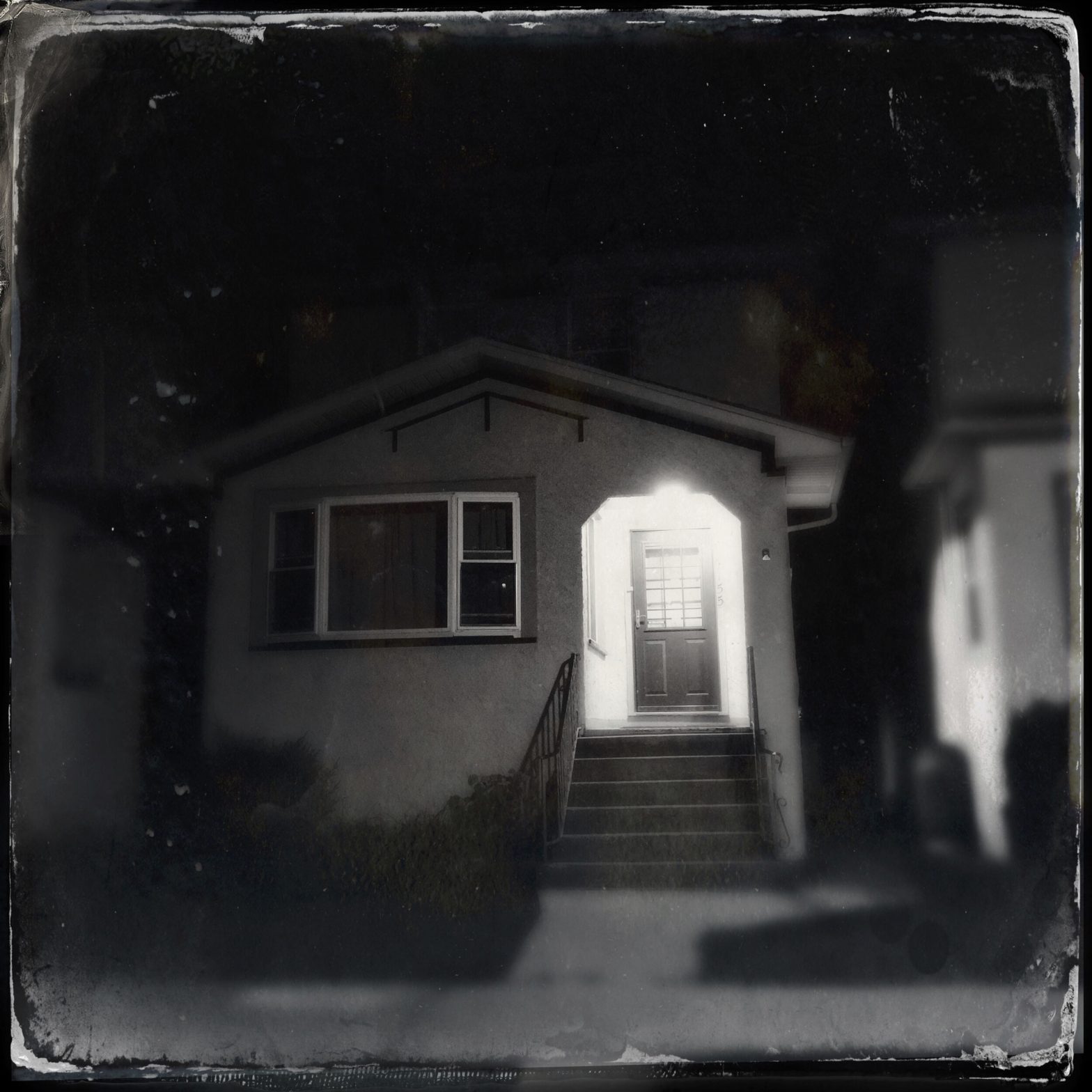

The House That Flowed Through to the World

There once was a house lived in by Mr. Him and his son and Mr. Hum and his son, and this house flowed through to the world. Mr. Him and his son and Mr. Hum and his son didn’t actually live all in the same house; they had two houses side by side, but where there might have been solid walls there were instead odd-shaped doorways that would just fit a man and his son.

And these doorways flowed from house to house, from building to business, from banker to blacksmith, school to sweet shop, carport to club (men’s club, of course). They flowed through to the world.

These doorways were quite a work of art, perfected over centuries. They were cut from oak, carved in intricate designs, the edges carefully beveled and all polished to a deep rich glow. They radiated manliness, as only oak can. And each was shaped to fit a man and his son. You could see the size and shape of the man’s work boots, the square corners of man and boy’s shoulder. Even the cowlick atop the boy’s head that boys can never quite comb down, was cut exactingly into this frame.

This is ridiculous, you might say. Boys grow taller! Men grow wider! A carpenter could work his whole life away and not keep all those doors in proper shape! And besides, neither Mr. Him nor Mr. Hum or either of their two sons had ever picked up a hammer in his life. . . . (Well, actually there was this one time, when Mr. Hum tried to hang a picture of his son. And oh, what was done to Mr. Hum’s thumb! Finally, he hit the nail so hard it flew through the wall and out the other side. It missed Mr. Him’s head by a whisker of an inch. This caused much consternation, as you can well imagine, and they decided no more pictures from then on. When they wished to remember them, they’d look at their boys.)

So who built these doorways, and changed them so often as sons grew taller and fathers grew wider? It can’t just happen by magic, you say. You say! It was magic of sorts, but not the sort of glitter dust in the air and poof! sort. It was elves. Who else? The carpenters of the world. And they didn’t just work at night when everyone else was asleep. How could they with all the doors that flowed through to the world to maintain? No, they buzzed among the men’s feet all through the day, and well into the night, tape measures out, now crouched on a shoulder, now riding through the air hitched to a man or boy’s belt buckle, taking measurements, marking patterns, sawing and hammering and filing the wood. And so skilled and quick were the elves, that no matter how far and wide and fast Mr. Him and Mr. Hum took their two sons exploring the vast breadth of the world, the men and their sons could always walk through the doorways, head high, shoulders back–a perfect fit. There was no place they could not go.

It seemed a near-perfect world . . . except for the blankness on the walls.

Then one day, something happened (it always does), to shatter the serenity, that sense of happily ever after that all fairytales have at the end, which has to be shattered before a new fairytale can begin.

This time it was not a big bad wolf, or a king dressed in a poor man’s clothes, or even an evil witch with a wart on her nose and a poison apple hidden in the pocket of her cloak. It was a Girl. Just a girl. Perhaps a little pretty. Though who could be certain since Mr. Him and Mr. Hum and their two sons really didn’t know how to judge such things.

One day Mr. Hum and his son woke up and found the girl in their midst. Well, not really in their midst; sitting in a corner quietly, waiting to be noticed. They’d gone about their business, had their morning coffee, read the paper, put on their coats to go for a stroll, and nearly stepped through the man-shaped doorway before they noticed her. Who knew how long she’d been sitting there?

But when they noticed, the quiet was over, perhaps for good!

Oh, the shouting! Oh, the surprise! It brought Mr. Him and his son running quick, as you might imagine. And then! Oh, the consternation! Oh, the recrimination! Of course the elves came running, too.

“Mr. Hum, what have you done? This is worse than the infamous picture-hanging incident!”

Mr. Hum professed his innocence–and he was, you know.

Nobody knew where this girl had come from. She hadn’t come through the man-shaped doorway, that was for certain. Perhaps it was magic of the glitter dust in the air and poof! sort.

The elves didn’t shout. They’re not the noisy sort. They leave that to their distant cousins, the dwarves. But they were puzzled right enough, and stood there scratching their heads, and some scratched their chins, and all wondered what they should do.

They all agreed: Mr. Him and Mr. Hum and their two sons and the elves (who were all men themselves) that it wouldn’t be right to cut a girl-sized hole into all the doorways that flowed through to the world. It wouldn’t be right, wouldn’t be proper, because . . . because . . . because . . . and finally they convinced themselves it just wouldn’t be safe.

“We must build her a room where she will be safe, where she can feel secure and protected, and special in this room of her own,” Mr. Him and Mr. Hum and their two sons and all the elves said together.

And so the elves built her a kitchen with a doorway just for her. Because she curved where men cornered, and she flowed where they jutted, and finally, because bits of her stuck out where bits just ought not to be. Where all the other doorways in the world were built for a man and his son, this was the only room in all the world with that unique-shaped entry. And while she couldn’t fit through their doorways, due to her odd-shaped bits, they couldn’t fit through hers, either. So that was fair, wasn’t it?

When it was done, the girl went into the kitchen without ever saying a word.

“See, she likes it!” they all cried. And Mr. Him and Mr. Hum and their two sons and all the elves congratulated themselves on a clever idea and a job well done.

And when the girl returned a short time later with food and drink she had prepared, they sat down to a meal, certain all was right with the world. (And never once gave a thought that she might just have been very hungry and hadn’t intended to share with them at all.)

Things went on like this for awhile, with Mr. Him and Mr. Hum and their two sons exploring the doors that flowed through to the world, but always they returned to Mr. Hum’s house, three times a day, so that the girl might bring food from her kitchen for them.

They never noticed the girl eyeing the elves, as they built new doors or altered old ones.

They never noticed her reading certain books–who knew from what odd world or other planet girl-things came from? Who knew what sort of dusty, poofy magic happened among them?

They never knew what shows she watched on their television–beamed in from who knew what solar system–while they were away all day. What man could stand to watch those women’s shows anyway?

They never saw her steal a forgetful elf’s toolbox, when he left it sitting in a corner one day.

But they heard the ruckus and the clatter! Of hammers and saws, and joists and drills, and files and levels, and bevels and beads! And they clustered around that girl-shaped doorway, trying to see in, but they couldn’t tell what she was doing. The noise continued for three days and three nights–and not once did she stop to bring food out to them!

Then everything was quiet. They peeked into that girl-shaped doorway again, shushing the elves who were hollering at her to give back the stolen toolbox. In one corner was a vaguely humanoid figure made of wood. Smaller than a human ought to be. With curves where there ought to be corners, that flowed where it ought to jut, and bits that stuck out where bits just ought not to be.

They saw the girl sitting on the floor with a pencil and a pad of paper figuring an advanced mathematical formula that scrolled over pages and pages. She sat there three days and three nights figuring. Until at last she came up with a number. It was the number of Woman.

Somehow, perhaps it was magic of the mathematical kind, she had figured out the equation for each type of woman that she had encountered in her books and on TV. There was an equation for the fairy princesses in the fairytales. There was an equation for all the evil witches and old hags. There was an equation for the good queens and bad queens and evil stepsisters. For kindly grandmothers and nosy neighbors. For servants and kitchen maids and slaves. For rocket scientists and nannies. Teachers and preachers and presidents. Nuns and bad girls with guns. For Nancy Drew and Trixie Belden. Mary, Rhoda, and quiet Georgette. For Mrs. Cleaver and Raggedy Ann. For Jeannie, a flying nun, and the identical cousins. For Barbie, Buffy, and Mrs. Beasley, Ginger, Mata Hari, Xena, and even Mary Ann. She factored all these equations together, then multiplied the sum by the square root of the total number of all the different types of women that could be in the world. Then she wrote this number down on a slip of paper.

From the doorway, the men saw her walk over to that vaguely humanoid figure she had built, open up the top of its head, drop that slip of paper in, and close the head up again.

Then the girl crossed her arms and waited.

And waited.

And waited.

By this time Mr. Him and Mr. Hum and their two sons and all the elves were quite bored, for they’d never had to wait for anything ever in the world. And so, tired of waiting, and convinced there was really nothing to see anyway–if the girl wanted to tinker in her own time that was fine, but she’d just better start putting out meals again, regular and on time, or there’d be trouble, just you wait and see!–they wandered off to do whatever it is that men did out beyond the doors that flowed through to the world.

But the girl had learned patience. The girl had learned to wait for things, sometimes a very, very, long time. Not once did she twitch or fidget or pace or sigh a deep sigh that wouldn’t this just please hurry up! She sat waiting quietly.

For three days.

And three nights.

And then, of course, something happened.

The vaguely humanoid thing wasn’t vaguely or-noid at all, but a Woman. Neither Mr. Him nor Mr. Hum nor their two sons, nor even all the elves (being men themselves) could name or recognize it. But the girl named it. Named it Woman. And with that name gave the Woman all the talents and strengths and knowledge that the vast universe held.

And the Woman opened her eyes. And she saw. Saw the way of this world with doors fit only for a man and his son. Saw the girl and all her potential locked away in this one room.

The Woman stood up. She hugged the girl. (Something Mr. Him and Mr. Hum and their two sons had never done, on account of their fear that those odd-shaped bits might be a fungus that they could catch.) And after that hug, that seemed to go on forever, the girl spoke for the very first time. And these were the words she said:

“I want to go through the doors that flow through to the world. I want to walk to the ends of the earth, and then come back again by a completely different route.”

The Woman said, “Yes.”

Mr. Him and Mr. Hum and their two sons and even all the elves (being men themselves) would have said, “No.” And, “It isn’t safe.” And, “What’s wrong with this very special room we built you?” But they had stopped paying attention to the silly antics of the girl long ago, and so weren’t there to stop her.

And even though the girl and the Woman still had the set of stolen elves’ tools, and knew how to use them, they didn’t bother with astounding craftsmanship, or intricate carvings, or carefully beveled edges, or manly oak polished to a deep rich glow. They didn’t bother making doors that would only fit their peculiar shape and stop all others from passing through. The only tool they took from that box stolen from the careless elf was a sledgehammer.

They broke down the man-shaped doors, first one and then the next, brushed aside the splinters, not much caring if they got pricked in the process, and the Woman and her daughter stepped through the wide-gaping hole, out into the world.

And that’s The End . . .

. . . until the happily ever after gets shattered again.

__________

Note: This story was first published in Daughter of Dangerous Dames, (Twilight Tales, 2000).

__________________________________________________

Tina L. Jens is the author of the award-winning novel The Blues Ain’t Nothin’: Tales of the Lonesome Blues Pub and has had more than 75 short stories published. In 2017, she received the Rubin Family Fellowship artist residency at Ragdale Foundation. Former editor of the Twilight Tales small press, she teaches the fantasy writing courses at Columbia College and advises the Myth-Ink student group for fantasy, horror, and science fiction creators. Tina occasionally blogs about writing at BlackGate.com and runs the monthly Gumbo Fiction Salon reading series at Galway Arms. Her recent publications include the poem “Lady Ella, She Don’t” in Ella @ 100, and a novelette called “The Patchwork Woman,” a retelling of the Bride of Frankenstein story, forthcoming in the anthology Gaslight Ghouls.