All the words in your head you could not say

You are having a party on your back porch. It is sunny and seventy. There is humidity and roses at the edge of the woods where you planted them hoping they might come up, and the aerosolized heat which drifts up on a straight southern wind from the Gulf of Mexico, some twelve hundred miles away, comes to where you sit now on the back porch. And you know if you were to say, can you smell it, can we all stop right now and just breathe, and smell it, all whom are sitting with you on the porch would think you are crazy. They would know that is your fatal flaw. Actually, two of your fatal flaws—one, you over-disclose whatever is running through your head and, two, you suffer from heightened insecurity over your over-disclosures. You have a third fatal flaw, and this one can actually kill you. You have an illness, a disease, a metastasis running through your body. You have not seen this cell, though others have. It is a genus of breast cancer called Her2. Nice name. Her 2 hertoo Hertwo. You search your rippling surfaces of thought for the wisdom she has brought you. You rarely reveal it to anyone—all these words in your head that speak of death. You would like to talk about death as if it were life—as if it were the same thing as life.

At least the yellow couches are working, if that can be said. Everyone wants to sit instead of stand, and you have thought about this—pre-thought the party and whether it would be good, whether the Humboldt Fog Ash cheese was over the top, whether you should have iced some sangria in a bowl. Maybe you want too much of everything, and that includes a perfect party. You think too much about everything—some people have said this to you, not great friends, but regular friends. You have three great friends and they all think too much along with you. They promote your spinning out. They talk about death, too, even though they aren’t actually dying as you are. Cancel that. They are dying. We all are.

Your friends have made fun of the Michigan sweet cherry wine that you are serving, being smartly ironic, asking for a glass then drinking it from the bottle and passing it around, saying no one needs a glass. One woman wears paisley prints, one woman ripped jeans with a black-silk shirt. The party is mostly women and that makes sense since, like you, they are gay—whatever that means. In the past, you have thought about it. Now being gay is nothing, or everything, or something in between, sort of in the seams of everything else that you are. It goes along with life and death. It is what it is at the moment. You’ve made a great peach pie. It means everything to have the peaches in season and to have gone out on the tractor that they run on the farm nearby and to have picked them. These are the peaches of yesterday. It was the best you could do.

All at your party commiserate with you about living out in the middle of fucking nowhere and, yet, all are living in the middle of fucking nowhere like you do. Your house is surrounded by trees, then some grass, then a forest understory, then the forest itself. The forest is an illusion as are most in southwest Michigan. It moves a few acres this way and that until it encounters the next neighborhood; the forest runs into houses up the street with pasture, or down the street with beach, and little by little it has been cleared for pasture or beach, or for no reason at all. After the Chicago fire of 1871, most of the forest on your side of the lake was clear-cut and sent over to the other side of the lake where your trees were used to rebuild Chicago.

Most of your friends live in nearby houses among the trees. You have looked up the forest system of Michigan, and it is unique. Fifty three percent of the state is trees. You live in a tropical depression, slightly below sea level, with winds off the lake keeping it warmer in winter. Seven forest systems find their confluence in Michigan. It is the northern most point for the yellow pine, the southernmost point for the Canadian hemlock and white birch forests. The lower peninsula is packed with beech and maple forests. Because of the mists that get swept off the lake and its many low-lying bogs, it is the most easterly point for cranberry crops. Also, the northern border for peaches. Michigan forests are growing, but not in diversity. Currently, there is a sycamore blight; the sycamores along the river have been stripped bare. The bark has been peeled back leaving a tree that looks like driftwood, their white, dying branch-fingers frantically combing the air. This follows the decline of the red pines from red pine scale and a fungal root disease. But the topic you want to talk about is that of the emerald ash borer. It has killed thirty million ash trees in Michigan so far.

Your friends at the party are talking about Poet’s House in New York and having known Allen Ginsberg when he was still alive. If they just looked at your forest they would see the trees fallen and slanting. But they are not thinking of a forest filled with fallen trees. There are other things to talk about. For instance, dogs—your dog. Everyone likes your little yellow dog and pet her as she goes from person to person begging for food. Your wife has told the story of how you picked her out from a sheet of mugshots of dogs who were about to be killed at a shelter in mid-Michigan. Your dog is part-whippet so it runs in vast circles, usually in front of the forest and not in it. The dog makes a white blur, a ghost line as she runs across, in front of the trees. She had a shelter name, but lately you are calling her ghost dog.

When you ask her to come and sit, her eyeballs, ears, and jowls jitter and shake until the moment you give the word and off she goes, racing through air again. You have noticed your own silence at the party and are thinking you should say something. You could talk of this dog, how she sleeps at your side after your chemotherapy, but you don’t. You don’t speak of anything.

There is so much you cannot say.

You have done the research, you have the words, and you want to speak of the millions of ash trees that have died in the state of Michigan alone.

For a while, the United States forestry service was looking into breeding insect resistant ash trees. When you googled ash trees, initially you hit on links on spreading ashes near trees and whether it was legal to spread ashes among the forests of Michigan. You found there were no state laws governing the spreading of cremation remains in Michigan. The irony was not lost on you.

You googled ash tree survival and found that the key might lie in finding trees that were resistant to the ash borer. Some universities, the University of Michigan and Penn State for instance, were doing studies on resistant trees. The emerald ash borer had been brought over from Japan. The insects arrived in Detroit, Michigan in 2012 via wood cartons made for cargo ships. They’re emerald colored, of course. They bore only into the bark of a tree separating the trunk from the nutrients in the bark. The tree dies slowly.

The Michigan Department of Forestry was asking for information on ashes, specifically, had you seen an ash that was surviving the emerald borer. If you had, the Department of Forestry would like to come to your tree and take a graft and collect samples from the tree, and perhaps, in some way, you thought, save humanity.

A few weeks before your party, you told your wife this. You told her you had seen such a tree. One that would save humanity.

You have also researched your own disease. You know the drugs you’ve been on, the drugs that are currently being studied. You go to clinicaltrials.gov, the national registry for all trials. You type in your Her2 cancer keywords.

You had seen such a tree. There was that ash down the road, healthy and leafed out. And it did not yet have the pencil holes in the bark that were the sign of the ash borer. The tree threw a half acre piece of shade across the lawn of your neighbor with the bocce ball court. The ash was close to the side of the house. It was larger than the house. It branched out across the street, the lawn, then ran along the house, back to the bocce court. The owners of the ash were driving down the street and you asked them if they knew what they had—the last living ash in the neighborhood. The only thing you knew about these neighbors is that they were called the Millers. Telling them about the ash did not improve the microscopic bit knowledge you had of them. Half your life you have wondered what would break the staccato code of not knowing someone. They were wearing white the day you saw them, and their car was also white, and they looked like the saints of the neighborhood. But they took a pass on knowing more about their ash. They did not imagine it as you had, as the Gilgamesh of Ashes, the Hercules of trees, the prophet tree leafed out again.

You took pictures of this ash for the Michigan forestry service. You had found there was a call-in line for citizens to report surviving ashes. Apparently, the plan was for a forest ranger to come out and inspect the tree and take samples. There was a hothouse at Penn State dedicated to propagating an ash resistant to the emerald ash borer. You followed up with the Penn State scientists. You called them, you sent messages, you sent pictures of your ash when a forest ranger asked for one. And finally, you called the Oregon department of forestry because using your forestry books and tree ID app, you found that your prize ash was an Oregon Ash. The Oregon ash had a lower crown. It feathered out into the atmosphere like the Joshua trees of the desert. Their lifespan was three hundred years. The Oregon ash was nobility compared to the green ashes of southern Michigan. You imagined that a ranger would board a plane shortly and bring a small case for samples and a small vial for seeds and you might entertain them for lunch. You imagined this immense achievement, this breakthrough for trees and humans alike.

Forestry funding had dried up. All the rangers told you this. Ashes were no longer being quarantined; they were no longer being studied. The ashes were a lost cause. The forestry service had written them off. Your conversations were shortened to “Sorry, sorry.” The studies had shown that the emerald borer would not jump to other species of trees. So the plan to eradicate the borer consisted of letting the ashes die.

You often took the ghost dog to visit the Oregon ash to see how it was doing. You have breast cancer and it is metastatic. And you wanted to talk about it. Most of the funding goes toward breast cancer detection and almost none toward researching your late stage disease. It happens. It happened to the ash tree and to you. You had been told you were an anomaly for surviving this long. Sort of like the Oregon ash of ashes. Yeah, well, no. . . anomaly doesn’t explain it. Anomaly is the container word. Anomaly is a show, it’s a show of what is different in one patient. It is not a cure unless you study the anomaly. But no one studies anomalies. They study masses of patients, not individual survivors.

Anyone left living in the future will be an anomaly and no one will know how they got there. You have often thought that.

You want to ask why no one talks about cancer, but you know why no one talks about cancer— really why. We are supposed to be concentrating on life. Life happens before death and death happens after, and somewhere there is a line in the sand. No one sees it as a circle, as a spiral, as a space that both could occupy. As I live, I die. As I breathe in, I breathe out.

Your wife is a filmmaker and a Buddhist. She understands impermanence. A moving picture is an effort to capture what will never be there again, not that it was ever there in the first place. When you walk outside of movie malls you pause with her to look at cars. Cars and their polish of paint seem unreal. The vast field of cars seems unreal. What is real is that you and she are riding waves of thoughts ghosted by scenes from a movie. You look for your car which you can never find.

You discuss film on the way home from the cinema. She likes Ozu who directed Tokyo Story. The film is about an aging couple who float about Tokyo in a diaspora. They have come to visit their busy children. They are not parents, they are aging parents. Finally, they are welcomed, almost as refugees, by Noriko, their daughter-in-law who is widowed.

The party has gathered steam because two people have just found they worked at the same nonprofit while living in New York in separate years. Only six months had separated them from knowing each other. So, now they talked quickly, wildly shouting and stiffening their hands when they find a name in common.

Everyone seems to know someone who was connected to others they knew. Just as the conversation about poets was getting going, you stood up and asked if anyone wanted to get out and take a walk. Take a walk where? Someone asked. You explained the disease caused by the ash borer; you talked about the ash tree down the road. You wanted everyone to see the tree that is surviving, even though it is dying—will surely die. You wanted to speak all your thoughts and second thoughts and triple do-overs of your thoughts. No one knew why they should leave your party to see the tree. You want to go right now? Someone asked. And you could think of a hundred reasons to get up and go, now! Each breath it would take to stand under the ash would be worth it. Maybe later. . . . You corrected yourself.

It is stories like these, about the dying tree, that can kill a party. You rarely get invited to parties anymore, or weddings.

You get why people don’t want to talk about it. You’ve been to survivor groups to talk about it—not the tree, but your cancer. Not even the survivor groups want to talk about not surviving.

And the wine and the bread and the hens outside in the new greenhouse. It makes you think of going to the lake, and sitting in the summer heat just to feel it.

Someone in the kitchen ask-shouts if it’s organic salmon, and yes! You shout back, Yes, it is! And, Where did you get it? They ask, holding the cracker of salmon in the air. Dinah Washington jazz classics are playing on your new speakers that you ordered for the party. The flowers you picked that morning are like a sunburst behind your friend holding the salmon. It’s a moment, a party moment. The conversation is roiling. Your friend from New York has been asked to redesign Harvard square. The East Coast critics have not seen the design, but have decided they hate the idea of redoing the square. And you will talk of the small building down the road that the county democrats just bought. So you are trying to make this party phenomenal, whatever that means. Phenomenal is a Caribbean-blue when you are actually standing in the Caribbean. It takes your attention. Perhaps there is light in our fingertips. You think this for as long as you can—seconds, minutes, and then you turn, knowing you have to go back to where you came from before you were standing in the Caribbean.

Parties are like that. A good party makes you realize that you are dying soon.

You asked your oncologist to change your drug to a targeted therapy, one that the FDA has just approved. Then you visited the head of nuclear medicine in his hospital basement office, which is where all nuclear medicine departments are. You asked him about laser beam radiation for your type of cancer at this late stage. He twirled on his doctor’s stool, but paused several times to look at you. “There are no studies,” he began, and then he continued to think out loud until he arrived at, “Why not?”

You are brushing crushed garlic and olive oil on the bread, then you chop fresh basil and garnish it. As you slide it into the oven, you think, Yes, this has meaning. You hold your fingertips to your mouth. Your hands smell and taste like basil. The front door opens, the ghost dog barks. It is the woman from down the block whom you met while walking your dog. You invited her to the party on a whim. She has worn a sunhat, which you like because no one wears hats to parties anymore. You decide not to analyze this further. You hug her. It is a waning electricity in your chest.

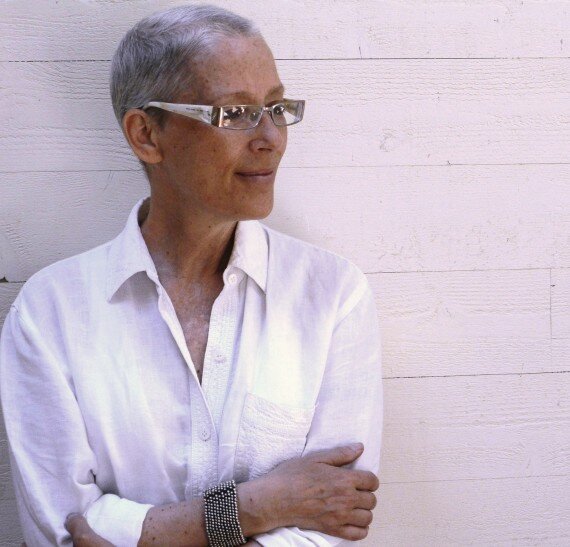

Re’Lynn Hansen is the author of To Some Women I Have Known. Her essays and memoir work have been published in Prism, New South, Florida Review, and Hypertext, and online at Contrary, and Slag Glass City. She has been awarded the New South Prose Prize, the Prism Creative Nonfiction Prize, and The Florida Review Meek Award. Her chapbook, 25 Sightings of the Ivory Billed Woodpecker, is about the personal nature of bird sightings. She is editor of Punctuate. A Nonfiction Magazine. She has researched early cancer vaccines at Yale’s archives for a memoir about living with cancer and she is among the first to receive a cancer vaccine in trials. Her website is at www.Relynnhansen.com