Sam talks about his writing journey, how to balance your life and writing, and tips for a future writer

I first discovered Sam Weller last semester in my Introduction to Literary Interpretation class here at Columbia College Chicago. I had heard great things about him from a previous professor at my community college, and the class was no disappointment. I was enthralled by his knowledge and experience in literature and his profession, including his past as Ray Bradbury’s personal biographer.

Through his spoken stories to his classes, you can tell just how much he has to teach the upcoming generations, and how much it means to him. His love for literature and teaching is one that is genuine. His work showcases his ability and talent as he delves into real-life topics, all the while adding his hint of science-fiction.

A journalist, fiction writer, and two-time Bram Stoker award-winner, Sam Weller is well known for his biographies of Ray Bradbury. His book The Bradbury Chronicles: The Life of Ray Bradbury was a bestseller and winner of 2005 Society of Midland Authors Award for Best Biography. It was followed by Listen to the Echoes: The Ray Bradbury Interviews in 2010 and in 2012, Weller co-edited Shadow Show: All-New Stories in Celebration of Ray Bradbury alongside Mort Castle. Sam was a Correspondent for Publishers Weeklymagazine and his own essays have appeared in the Paris Review, Slate magazine, and more. He is a current blogger for the Huffington Post. More recently, Sam’s fiction has been featured in various outlets such as Printer’s Row Journal, Rosebud, and the Chicago Reader among others. Upcoming, we have a lot to look forward to. Sam Weller is currently working on his debut novel and in 2020 he will be releasing a collection of short stories titled Dark Black.

* * *

I’d like to start by noting your previous work. You’re well known for your work as Ray Bradbury’s authorized biographer. What are a few of the key things you learned while working with him?

Ray taught me so much. First of all, he was creatively fearless. He was a tremendous creative risk taker. He wrote short stories, novels, essays, poems, screenplays, teleplays, radio dramas… He did whatever he wanted. This is what I try to emulate in my own writing career. I have done a travel book; a biography; a book of interviews; comic books; a graphic novel and, next up, I have a collection of short stories coming out in April. I don’t want to be confined by boundaries as a creator, and Ray taught me this.

Another important lesson is that he taught me to trust my creative intuition. As readers and writers, we are constantly training our subconscious in the art of storytelling. Ray often said, “Your intuition is smarter than you are, so get out of its way.” So, with this in mind, if a story keeps tapping me on the shoulder and saying “write me,” I listen! I don’t question where the story wants to lead me, I try to follow. When a story is really working, it almost starts to write itself, the writer is just the medium to channel the ghost.

Besides Bradbury, what stories and/or authors had a strong influence on you and your writing?

So, so many. I love writers who have an electric energy to their narrative movement. Tom Wolfe’s The Right Stuff is absolutely voltaic. That book was a towering influence on me. Same with Lester Bangs, the greatest rock-music critic ever. James Wolcott, the essayist, critic, and fiction writer has a similar lightning to his wordsmithery. I like to take this energy over to my fiction. Other important influences include Truman Capote, James Baldwin, John Steinbeck for sure, Louise Erdrich, Joan Didion and contemporary writers such as Joe Hill and Charles Yu.

You’ve had short stories published and have written for various magazines in the past – as a journalist and author, where did that journey begin for you?

As long as I’ve been writing nonfiction, I have been writing fiction. The commonalities between the two genres are far more pronounced than the differences, really. A story is a story. It needs to be told well, using all the senses, with memorable scenes, a sense of play, experimentation, use of narrative forms, dialogue, narrative movement and more. These things cross easily between nonfiction and fiction. And a story must be told in your voice. Like a great guitar player, you really should be able to recognize a writer’s signature very quickly. So, I have been writing fiction for years. My MFA is in fiction. My stories have been published in a number of anthologies, as well as in literary journals. After writing THE BRADBURY CHRONICLES: THE LIFE OF RAY BRADBURY (William Morrow, 2005) I was ready to get away from heavy research and interviews and footnotes and indexes and facts for a while, to just take a break, so I started publishing more and more short stories. This journey has been one of pure joy.

How did your journey lead you to where you are currently?

Well, I’ve been writing and publishing short stories for the last decade or so and it’s led to my first short story collection coming out in 2020. I’m very excited about it, but I’m now ready to get back to a huge nonfiction project that will take me deep into the research mines again! I was at the New York Public Library a few weeks ago in the rare manuscript room and my heartbeat sped up. It felt like Indiana Jones and Hogwarts rolled into one.

In Spring 2020, you have a collection of short stories being published. It’s a little different than what you’ve published previously. What was the inspiration for these stories? Without giving too much away, is there any more you can tell us about them?

One of my favorite books by Ray Bradbury is 1955’s, The October Country. It is very dark, very melancholy, deeply poetic and — psychologically — quite creepy. It is one of his finest short story collections. I wish he had written more stories in this tradition. The October Country got me interested in “weird” fiction, and then I went deep into the light-deprived rabbit hole of Gothic literature and haven’t returned. I noticed that most of the short stories I was writing were cut from this sort of dark, velveteen cloth. My subconscious was writing a collection of dark stories long before I saw the thematic connections. My book, Dark Black comes out in June of 2020. It includes twenty short stories. I played with narrative forms in some, one is written as a found transcript of a conversation; another is written as a sort of fictionalized, rock-music magazine feature story. I love playing with contemporary forms in the constructs of fiction. The title story of the book is one of my favorites. It is about an oceanographer who is at the end of his career and sets out to prove the existence of the mythic Kraken, something he is convinced he saw early on in his career. This story is sort of Moby-Dick meets Jaws meets my love of Kaiju monsters. The story is sad. It is very cold and autumnal and, strangely, reflects that I was listening to a lot of John Denver when I wrote it. It caused me to reflect on John Denver’s death in a plane crash, and how he died flying, which was something he loved very much.

Death is the pervasive connection between all of the stories in Dark Black. Death, grief, loss, loneliness, isolation and madness—the hallmarks of Gothic literature. I lost my Mom when I was in my early twenties. I lost Ray Bradbury, who was really like a second father to me, in 2012. I lost my childhood best friend in a car accident and one of the stories in the book (“Conjuring Danny Squires”) is a fictionalization of this tragic experience. I think the only way I could begin to grapple with all of this loss was to allow life to come from it—life in the form of story and art. Creativity is the flower, the miracle, that grows from the drought striken landscape. It’s very gratifying that Charles Yu called the book “haunted and haunting,” as this was my intent with this new book.

The final thing I will say about Dark Black is that it was very important to me to have every story include an illustration. I wanted the illustrations to be as haunting and desolate as the stories themselves. My publisher got this aesthetic immediately. They said, “Go for it!” They didn’t worry about cost. They just said, “Do it.” The art is all done by artist and printmaker Dan Grzeca, who is best known for his work rock bands like the Black Keys, Sharon van Etten and U2. In many ways, his art is the visual twin to my stories.

I’d love to know what your creative process looks like. When you sit down to write, do you have any rituals? What does your environment look like?

Music has always been absolutely imperative to my writing process. I have always listened to music when writing. Every project I have ever worked on always had an unexpected soundtrack that I listened to as I created—sort of a musical mood that painted a color and vibe. I listened to a lot of punk while writing Dark Black, as well as lot of Johnny Cash and old Irish folk songs. Most of the music was about broken hearts, broken people and redemption.

I would love to be precious about my process, but I really can’t afford to be. I would love to be able to rent a cabin somewhere in the woods to go away and just write. I could get so much done! This is a dream of mine, one day. Or to buy a small farmhouse somewhere. But I have three kids and really can’t do that. At least, not until they are a bit older. My years as a staff writer for alternative, weekly newspapers fostered in me an ability to write anywhere. Journalism is great training this way. Newsrooms are loud and people are constantly talking to you and you just have to stay focused. Edward R. Murrow wrote on battlefields, so I figure I can write in a loud house. I write sometimes on my phone using the memo app. I can write pretty much anywhere. It’s not ideal, but it’s how I get things done.

One thing I do like is to have several hours to get in a groove. I don’t like to only have 15 minutes here or there. I hate writing like a lurching car with a sputtering engine. I want to get on the highway and go for a long road trip. I am also very much a morning writer. I love the energy of the morning, with the promise of the day out before me.

You’re a father, a teacher, and a writer. How do you find the time to write?

Balance is the hardest part of my creative life. I have no answers. I fight for my creative time. That’s all I can say. If I don’t write, I get depressed and feel caged. So that’s good motivation to constantly look for an opportunity to be creative. I’m also a much better teacher when I am engaged with my creative practice. I’m also a better father because I am a happier person. Somehow, someway, I make the time.

Going off my last question, do you have any tips for those struggling to find a balance between their writing and life?

You have to want this career. You have to fight for it. You have no choice. If you are a writer, you must write. And cut it with the procrastination. Don’t do it tomorrow. Do it today. No one is going to facilitate your dream but you.

To end the interview, what would you say to those writers who are struggling to not only find their voice but also their footing in the literary world?

Don’t despair. We all feel these things. We all question our voice, or tire of the sound of our own voice because we are with it 24/7, on every page, in every sentence.

Write about the things that fascinate you. Be curious. Be an active listener. Be an active reader. Write with passion. Write the story you would want to read. Writing like this will never let you down. Ray Bradbury taught me, “Do what you love and love what you do.” So write what you love! If you do this, the story will take care of the rest.

Interview by Alison Brackett

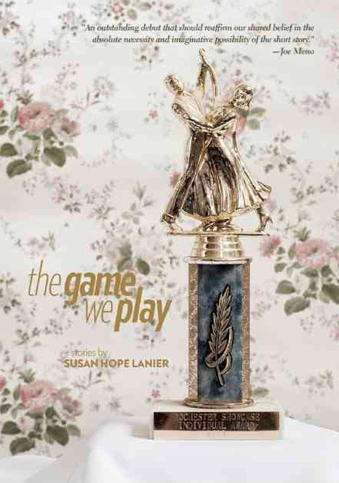

Dark BlackHat & Beard Press

254 pages

https://hatandbeard.com/products/dark-black

The Ray Bradbury Chronicles

Published by HarperCollins Publisher on April 5, 2005

ISBN: 006054581X

383 Pages