Patience

To what lengths would you travel to save a lost love? This question is what lies underneath the surface of Chicago-born comic book artist Daniel Clowes’ latest graphic novel, Patience (Fantagraphics Books, 2016). A book self-described as, “a cosmic time warp deathtrip to the primordial infinite of everlasting love,” Clowes expounds upon themes of love, loss, despair, obsession, and hyperrealism presented in previous works, while adding sci-fi elements of time travel, ray-guns and parallel timelines into the mix for a book that, although is severely tied to earlier works, stands out as one of his most unique and heartfelt to date.

The graphic novel begins in 2012, where relatively happily-married Patience and her husband, Jack, discover that Patience is pregnant. This leads to the usual woes of an expecting couple: what clothes should we buy for the baby? Do we make enough money to support this family? Will we be bringing this child into a less-than-acceptable future? One day, after returning home from his less-than-financially-satisfactory job, Jack finds Patience dead on their living room floor, supposedly murdered by an intruder. This leads to a whirlwind year of Jack being prosecuted, tried, and eventually imprisoned for ten months until his name is cleared, due to insufficient evidence. After being released, he conducts his own investigation, leading nowhere. Jump to 2029. There’s clubs with drinks served in scientific beakers, blue women in LeeLoo Dallas-esque attire and “Super-Creeps” in yellow Hulk Hands; this future is not quite Jetsons, no flying cars and floating buildings, but far from A Clockwork Orange. Jack is still severely depressed from Patience’s death and has been living in a self-loathing, obsessive freefall until he finds a man named Barry that has created the ability to time travel, and all hell breaks loose as Jack jumps from 2006 to 1985, and back to 2012, disastrously interacting with past incarnations of pivotal characters, including Patience.

Clowes’ exploration in Patience of lost love and the depths we as humans are willing to dive to retrieve retribution is a modification of themes explored in his earlier works, specifically David Boring (Pantheon Books, 2000) and Like a Velvet Glove Cast in Iron (Fantagraphics Books, 1993). But where Clowes utilizes the main characters of Boring (David Boring) and Velvet (Clay Loudermilk) as mediums for the idea of closure (i.e. Boring searching for a woman he considers his feminine ideal who previously abandoned him, and Loudermilk searching cross-country for his estranged wife after seeing her in a BDSM snuff film), Clowes has progressed to using Jack Barlow as a tool of retribution, a man so obsessed with the loss of his late wife he is willing to travel through space and time itself to avenge her.

In this journey to find and stop Patience’s killer, he becomes obsessed with attempting to better the lives of past incarnations of Patience, bringing forth several moments of moral ambiguity and complexity throughout Patience that rings true to Clowes’ style. For example, when back in 2006, a middle-aged, time-traveling Jack beats a teenage boy half to death that sexually humiliates Patience. At one point, thinking Patience’s con ex-boyfriend, Adam, was her future killer, Jack goes back to 1985 to when Adam was a child and almost murders him, to which he rationalizes and pontificates:

I can’t tell you exactly what happened. It sure as hell wasn’t because I couldn’t shoot a baby; nothing like that. One thing about a guy with my perspective—once you know how the story ends, you don’t much give a shit about human potential . . . And it wasn’t because I might fuck up the future . . . No, it was like some invisible force of nature took over for a second. I wanted to broil that little fucker so bad, but I just couldn’t pull the trigger.

Though these appear to be terrible deeds on Jack’s behalf, they are carried out with the full intent to continue the life he and Patience had, as well as attempting to make the life she had prior to their meeting and eventual marriage—to which she earlier expresses much disdain for, to the point of never talking about it with Jack—easier, effectively asking the reader the question of, “would you take a life to save the life of a loved one?”

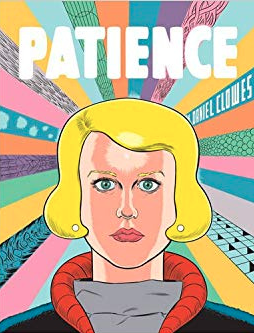

The hyperrealism at play with the elements of sci-fi of the plot is further pushed through the artwork of Patience. Relatively drab, muted colors and stark line-work are on display in the years of past, while when in the future that level of realism is literally layered over with vibrant colors and rotund figures. It is almost a bit jarring to see Jack with his colorful future technology in Clowes’ visual idea of yesteryear.

Daniel Clowes wrestles with ideas of love and loss in Patience, often times forcing the reader to ask themselves questions throughout about the things they would do, the depths they would sink to, and the sacrifices they would make to save a loved one. All the while letting the reader know ultimately no matter what you try, no matter what you do, that some outcomes are inevitable, but that for the ones that are capable of change, that change might not be immediate and often times one must exercise a certain degree of patience.

Davis R. Blackwell is a Chicago-based author. You can catch him ignoring you on the Red Line eating a six-piece chicken dinner from Harold’s.

June 19, 2017