I Set a Fire

I don’t know why I set the fire. I haven’t wanted to think about it since. Though I know what I joked for years afterward— “We had to find that baseball didn’t we?” Like I’d been one more dopey kid.

It was a brutal July day that summer of 1955, not far from the ocean, and a too long bike ride away from the center of our small Rhode Island mill-town. I was about to turn twelve and enter the seventh grade. There’d been a steamy haze that morning, but now the sun was out full and what air that moved came warm off the land. Nobody wanted to play baseball, nobody, especially not slow-moving Earl. “Too hot,” Earl said, “too hot,” and it was, and still I pushed him to the ballfield right across from Dr. Gongaware’s and my big house on the hill. Dad called me “a bull.”

The game I wanted to play was my game with two players (call it “catch”), a game almost as good as our regular five against five, our neighborhood too little for baseball’s usual nine on a side. I played shortstop and Earl played first, his back to the high grass that surrounded the field the Gongawares mowed for us kids.

I stood at short on the yellowing grass and faced first base as Earl got ready, the unlevel field sloping down behind me to the missing leftfielder. Was that smell honeysuckle? I waited in the hum of insects and the flash of redwing blackbirds, the smell of saltwater heavy in the air, a seagull drifting down to the backstop behind home plate. The heat. The quiet.

“Come on, Earl, let’s go. Roll me one.”

Earl was a class grade behind me though we were about the same size. He never hurried, unlike his father who worked a machine at Cottrell’s factory and was always in a rush to a new home-project: “Why are those goddamn boys never around when I need ‘em? Where’s that lazy Earl?” And despite the hurry and the anger, he’d look at me and smile: “Howya doin’ Butchy-boy?” (Butch, my family nickname). Did he hope my straight A’s would rub off on his sons?

Earl took his time, and finally rolled an easy grounder at me and I charged it in a low crouch, gloved the well-used ball, and fired a rocket back. Earl shook his gloved hand in pain.

“You have to throw that hard?”

I didn’t answer. My arm was my one baseball talent. I couldn’t hit, I wasn’t the best fielder, he’d have to stand the pain. And even so, the problem was larger—I threw wild. We’d search for the ball in the high grass for forever.

“Jesus,” he whined. “Throw straighter why don’t chu. . . .”

I’d get better. I had to. I dreamed of being as good as the Yankees’ Phil Rizzuto, or maybe just better than I’d been the day before. I had to get better to be someone, to prove that I mattered, to prove I deserved respect on the field and was more than a “brain.” Work was the way. Dad said so: “Do every job right or don’t do it at all.”

I threw over Earl’s head the fifth time and he glared like I’d made him swallow puke.

I glared back. “Why don’t you learn how to catch?”

The pain in his hand, the searching, my pushing—ate at Earl. We were baking in the soggy late-afternoon sun and pouring sweat, t-shirts stuck to our backs, blue jeans gummy on our thighs, BVDs grabbing at our crotches.

Find the ball, find the ball, the only ball we had, the ball we’d used the whole summer. Why’d you lose it? kids’d say. How’d you lose it? Who’s gettin’ a new one?

Not me. And definitely not Earl. He didn’t like baseball that much. Anyway, who had the money? I’d saved two years from my paper route for the Dee Fondy first basemen’s glove he was using.

Earl tromped around in the grass in his black high tops. “Where’s that stupid thing? Come ahhhhnn. Come aaaahhhhnnnn . . . .”

He couldn’t stop groaning. “We should block out areas,” I said, “cover ground a small block at a time. Ball couldn’t have gone far.”

Earl ate early and he had to go soon or his father would yell when he came home from the mill and parked the rusted Chevy in their dirt yard: “Where are those damn boys?” His father’d moved the family out here by the saltwater to get Earl and his brothers away from the reform-school kids in town. No one fooled with his father.

Earl tromped into my block again.

“Hey, get out! What’re you doing? What’s wrong with you?”

The sun beat down, the dry grass scratchy on our arms as we moved around now on our knees. We’d lose the ball and the older kids’d rag, You crapheads never do anything right. You’re lucky we let you play.

I knelt in the grass and lit a match—why was I carrying matches?—and the fire took off in the off-shore air. The fire would burn the top of the grass and leave our ball buried below untouched, at least that’s what I hoped.

The flames spread, they flew, it was fire season, and they burned the dry brown grass all the way down to the ground. The fire’d scorch the ball and leave a black nothing, a black and brown nothing we couldn’t use, we wouldn’t use.

Earl slapped at the flames with my brand new first baseman’s mitt and I slapped with my old falling-apart infielder’s glove. Earl peeled off his clammy t-shirt and tried that. Nothing worked. Nothing. And I could see my house not far up the road. Dad ran the state forest service and wore a .32 for “those crazy sons-a-bitches” that set fires.

“Call the fire department,”I yelled, Earl’s house a good half-mile away and we didn’t have our bikes. “I’ll go get help.” Earl ran for home, and I ran for the house across the road, the Gongawares.

What would they say? We used their field with the bases and backstop, and drank from their freshwater spring, even ate apples from their trees when they weren’t looking and now I was torching their grass, their land, maybe their orchard, the blueberries, the lilacs, the rhododendrons, maybe their house . . . maybe mine.

No one outside. Was anybody even home? I pounded on the door, chest rising, chest falling, I couldn’t get breath. I pounded. No response. I pounded. The door opened, a woman my mother’s age—lean, a tight jaw. Her disapproving sister would be my English teacher in September.

“Fire. We’ve got a fire.” I didn’t say why, I didn’t say how big. She turned and disappeared into the house while I stood in the open door gasping. Was she phoning for the fire trucks?

She came back with two long, wooden brooms and handed me one, and nodded in the direction of the field. I ran, my left arm thrashing about with the broom, and she ran too and said nothing, back across the road to the field, her head down and broom thrashing about like mine, skirt churning around her legs, and . . . we were at the fire.

She bent from the waist and whacked the flames with the broom, her long hair falling into her face. She whacked and I whacked. Her house might go, my house might go, our field, her field, our world, her world, and my fault, I had to do it my way—for a game, for a ball, my bottomless wanting.

I beat the flames and she beat the flames. How did she know this would work? I could feel my arms and back, my wobbly legs, the rasp of my breathing, the broom, my eyes filled with sweat. Could we win? I lost track of time. . . .

And the fire seemed to diminish slightly, ever so slightly, grow smaller, to ease off and die away, a few flares, some last flickers.

Mrs. Gongaware and I straightened up and leaned on our brooms. A woman I didn’t know, my neighbor, side by side with her in a scorched field, and we examined our work in silence. The blackened grass, some scrub pines burned, some tiny shrubs burned. . . . But not the lilacs, not the blueberries, not the raspberries, not the goldenrod and honeysuckle, not the flowering purple and pink and white rhododendrons, not her house, her house still standing, and my house. . . . What will Dad and Mom say? And what is Mrs. Gongaware thinking—the field, the fire, us kids. Is this the end of baseball?

I heard sirens, trucks, fire trucks, men I knew, men who knew me, Swamp Yankee volunteers my father fought fires beside. What will I say?

___________________

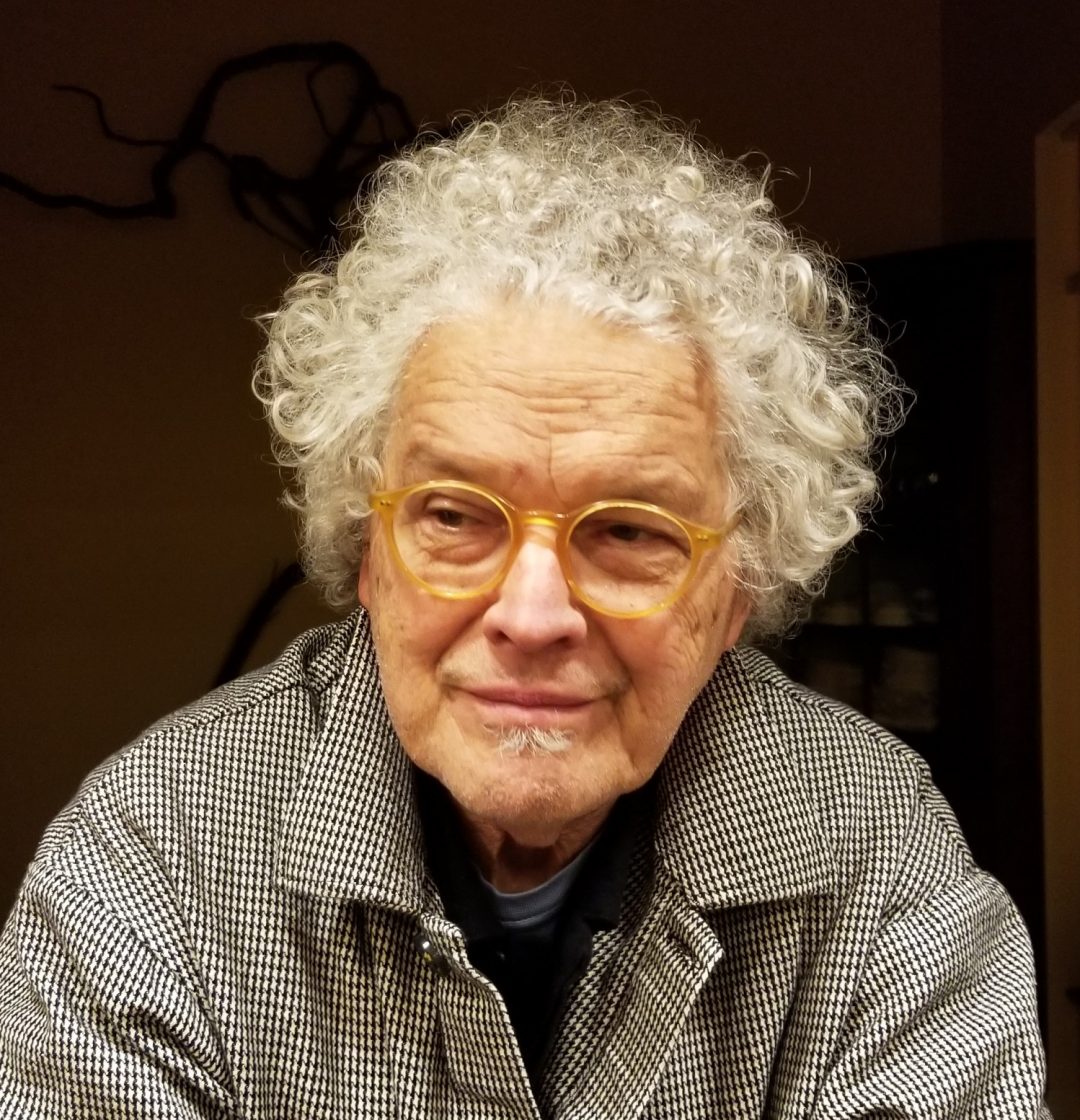

Kent Jacobson taught for nearly 20 years in Bard College’s Clemente Course in the Humanities, a 2015 winner of the National Humanities Medal. His nonfiction has appeared or will appear in Hobart, Under the Sun, Thread, Brown Alumni Magazine, and Northwest Review, among others. He lives in Massachusetts with his wife, landscape architect Martha Lyon, and their English Setter puppy, Ben.