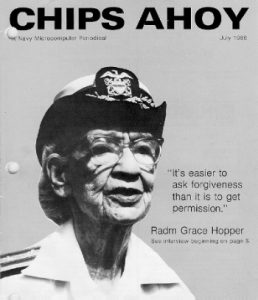

It’s easier to ask forgiveness than it is to get permission. This handy little phrase has been invoked since at least the mid-1980s. The idiom was coined by Rear Admiral (and Yale PhD recipient) Grace Hopper in a 1986 edition of the US Navy’s Chips Ahoy magazine, or so says my cursory research. Today it is invoked as a kind of get out of jail free card by anyone from big business CEOs crushing the competition in the name of progress to teenagers getting caught sneaking back into the house in the wee hours of the morning. But should we apply this catchy maxim in the realm of creative nonfiction?

Welcome to the sticky realm through which we creative nonfiction writers, unlike our kin in the poetry and fiction genres, must tread. If we’re writing the truth or an even the truth as we see it, the most basic way to establish our credibility is to use the actual names of those we are writing about. And if what we are writing is true, why would we need to ask permission to use it? Simple right?

Not so simple. If the individual we are writing about is a living person or, worse, the wealthy estate of a deceased person, then we find ourselves thumbing through our well-worn copies of Slander for Dummies before our first draft is even completed. This is because the threat of legal action looms over us like the shadow of a giant lawyer with a cease-and-desist letter. In this regard, only journalists have it worse—they have to do a lot more than a Google search to prove the factual value of what they are writing.

Defamation! Libel! Misappropriation! Negligence! Malice! Invasion of Privacy! These terms swirl around the mind of the creative nonfiction writer like leaves in an autumn wind. Horror stories abound where an individual is portrayed negatively in a story or book, sues the author and publisher, and receives a hefty award or settlement in the end. Suddenly, the advance the writer received isn’t worth quite so much.

The author can choose, of course, to portray said individual in a positive—or even a neutral—light, but where is the integrity if this portrayal is not true? Maybe that’s where nonfiction gets creative. Remember that important rule of writing, the one that says, “show and don’t tell?” Write your piece so that the readers will be able to formulate their own opinions about your subject matter.

Sometimes, it’s not even a matter of legal repercussions stemming from a questionable characterization. Some individuals, unlike narcissistic writers, don’t want notoriety of any kind—even if you are writing an ode to their many virtues (which, by the way, would be poetry and not creative nonfiction). Seeing their name in print for any reason whatsoever is disconcerting to them. The writer’s decision to “ask forgiveness” then becomes an issue of scrupulous social conduct and graceful personal behavior.

Maybe it is easier to ask forgiveness than it is to get permission. I’m sure that’s a key to succeeding in business (editor’s note: the blogger does not have a business degree) and that it works when one needs to make up with their partner for losing the rent money at the casino. But in creative nonfiction, it’s different.

If you want to use someone’s name in your work, ask permission. In writing. That’s the most honest piece of nonfiction any of us is likely ever to compose.

Andrew Krzak, Assistant Editor