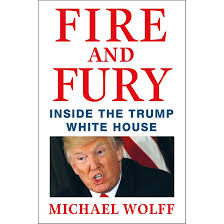

Reading Michael Wolff’s account in The Hollywood Reporter about how he got access to the West Wing while writing Fire and Fury: Inside the Trump White House got me thinking about Lillian Ross, the longtime writer for The New Yorker, who died last fall at the age of ninety-nine. Ross’s dictum, “Your attention should always be on the subject, not on you,” was most famously on display in a profile she wrote for the magazine in 1950.

Reading Michael Wolff’s account in The Hollywood Reporter about how he got access to the West Wing while writing Fire and Fury: Inside the Trump White House got me thinking about Lillian Ross, the longtime writer for The New Yorker, who died last fall at the age of ninety-nine. Ross’s dictum, “Your attention should always be on the subject, not on you,” was most famously on display in a profile she wrote for the magazine in 1950.

Ernest Hemingway—who had just turned fifty—and his fourth wife, Mary, were stopping over in New York on their way from Cuba to Italy. In the time Ross spent with the pair, they shopped for an overcoat, drank Champagne at ten in the morning in their suite at the Plaza hotel, and listened as Marlene Dietrich—who lived at the Plaza and who had just turned fifty herself—described her typical evening spent babysitting her grandson, cleaning her daughter’s apartment, and then taking a cab home to the hotel, with the young family’s dirty laundry.

Though Ross wrote dispassionately and offered no judgement on what she had seen or heard, the resulting The New Yorker piece, “How Do You Like It Now, Gentleman?” set off something of a furor when it was published in May of 1950 for the portrait of the man it revealed. Hemingway at fifty, it seemed, was a voluble galoot with tape on his glasses and a compulsion for sports analogies. For his part, Hemingway liked the profile, calling it “a good, funny, well intentioned and well-inventioned piece,” in a letter to A. E. Hotchman.

Though both Wolff and Ross practiced what has come to be called “access journalism,” Wolff eschews Ross’s “fly on the wall” approach for that of a guest at the table of the subjects he covers. In that respect, it is not surprising that as much of the conversation surrounding Fire and Fury was about Wolff and his methods as it was about the revelations contained within—as mind-blowing as many of them were. That may have largely been because the portrait of Trump as a self-obsessed, paranoid glutton presiding over an incompetent, back-biting staff surprised exactly no one. Therefore, talk quickly turned to the question of how the White House communications staff could have been so incompetent as to greenlight this tell-all.

What was surprising was that after dominating the public conversation for a little more than a week, nearly all talk about Wolff and his book disappeared from the internet and the airwaves. It is likely the nausea-inducing pace of political news under the current administration has a lot to do with that, but another explanation may lay in the nature of the writing. Since Ross’s day, the best nonfiction profilers have taken advantage of the access they were afforded into closed societies to reveal the humanity of the people they encounter, as Ross did with Hemingway and Marlene Dietrich. Whereas Wolff’s only apparent interest in people is what they can tell him about other people.

Of course, Trump is too invested in his own bloated self-image to be made interesting, much less human, but the book is not about Trump. Imagine how revealing it would have been to hear the inner thoughts of a young aide in Trump’s chaotic West Wing, juggling the job descriptions of three unfilled positions, while lacking the education, training, or institutional knowledge of the three veteran functionaries who had held those positions in the previous administration. How interesting it would be to hear the interior monologue that begins each morning as she dresses in the dark to start another eighteen-hour day in the service of a man she has come to see as a crass buffoon surrounded by sycophants and in-laws. Such were the people who Wolff walked past on his way into Steve Bannon’s office.

The gossip is fun, especially when dished by unscrupulous people with an axe to grind. And the facts revealed will add to the public record from which future generations will seek to understand that which is so difficult to conceive of, much less endure. But the book, like so many objects of this transactional age, is deposable.

In our February issue, we have four examples of more thoughtful reflection: An essay by Mark Dostert on overcoming a common, nagging writing habit. The piece references Hemingway, himself a prodigious dispenser of writing advice. “The Professor’s Body,” by Natania Rosenfeld, an exercise in familiarity through disassociation. Timothy Parfitt reviews the anthology Writers Who Love Too Much: NewNarrative 1977-1997. And we offer two exercises in craft by assistant editors Lauren Antonelli and Tabitha Chartos.

Ian Morris, Managing Editor