On writing novels and stories for Businessweek

Interviewed by Cody Lee, Reviews Editor

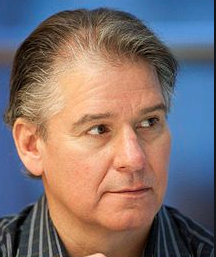

I bartend at a little Irish bar on the north side of Chicago, and people come and go every day—mostly bodies without faces or names. However, I remember first seeing this fellow sitting in the back, typing away at his computer, a stack of papers by his side, and a PBR in his glass. My manager, well aware that I consider myself somewhat of a writer, too, jumped on the opportunity to tell me that that’s Bryan Gruley, a Pulitzer-winning author that lives in the neighborhood. I didn’t believe him, so I googled the name, and there it was.

Fast forward a couple of weeks, and Bryan and I chat about books, and the processes of writing. I give him a drink or two free, and in return, he supplies me with some of the knowledge that he’s picked up over the years, dealing with agents and publishers, etc. etc.

He is the author of three mystery novels, and currently works as a reporter for Bloomberg Businessweek.

Cody Lee: What would you say is the difference between writing professionally and writing for fun? How would/should students entering the “real world” bridge the gap between the two?

Bryan Gruley: I don’t make much of a distinction between writing “professionally” and writing “for fun.” I suppose by the former you mean getting paid to write, but I have as much fun writing stories for Businessweek as I do making things up (for which I also enjoy getting paid). My first piece of advice to any aspiring writer is simply this: Ass in chair. Write. Write every day, whether you’re getting paid or not, whether it’s fun or not (some days are more fun than others, if you know what I mean). If you can find a forum for your writing, be it a website or a magazine or a book publisher, all the better. The only way to find the forum, though, is to write. I have a quotation taped to my laptop, supposedly from the novelist Jack London. It says, “You can’t wait for inspiration. You have to go after it with a club.”

CL: First published novel—could you walk us through the steps it took to get there? What did the aftermath consist of?

BG: I’ve wanted to write novels since I was in grade school. I took a pretty serious detour to nonfiction by way of newspapers from Kalamazoo to Washington D.C., to Chicago. In retrospect, it was also a necessary detour, because I didn’t have the personal experience nor the skills to write a novel until I actually wrote one. In 2000-01, I wrote about 25,000 words of a novel that my agent did not like. There was a glimmer of hockey in it, though, and my agent said, “Why don’t you write me a story about these middle-aged guys who play hockey in the middle of the night?” I had an idea that very instant.

It took me four years to write Starvation Lake. Then I endured a year of rejections—twenty-six in all—before the Simon & Schuster imprint Touchstoneoffered me a three-book contract. That was an exciting day in 2007. The book wasn’t published for almost two years. I wish I could tell you why, except to say that the publishing industry doesn’t move quickly. Meantime, I wrote what I thought would be the second book in the series. It wasn’t very good. I basically threw it out and started over. Seven months later, I turned in The Hanging Tree, much improved. In between, I enjoyed the thrill of being a first-time author. The best part was traveling around and talking with friends old and new about the town and characters I’d created. Starvation Lake sold very well for a debut, but I wasn’t about to be able to quit my day job.

CL: What, in your opinion, is missing in contemporary literature?

BG: I can’t really say. It’s a little embarrassing to admit, but between writing for Bloomberg Businessweek, working on my next novel, playing hockey, and enjoying my family and friends, I don’t have the time to read as much as I’d like. I do read almost every night before going to sleep, but not widely enough to answer your question. That said, my favorite book of the last couple of years is a contemporary novel, The Art of Fielding by Chad Harbach. It’s old-fashioned in the sense that it takes its time about moving the story along and developing the characters. Great story, great writing. I looked forward to picking it up every night.

CL: What would be your critique of schooling, and how could teachers and programs (specifically, related to writing) better prepare their students for the writing community outside of a school system bubble?

BG: I honestly don’t know enough about what’s happening in academia to answer the first part of your question, but the answer to the second one is simple: Write. Or, as my friend the essayist and novelist Brian Doyle told me years ago: 1) Ass in chair 2) Type better than sixty WPM 3) Shut up 4) Get a job. If #4 is a job that pays your bills, all the better.

CL: How important is understanding business as a writer, if at all?

BG: If you mean the importance of understanding the business of writing—selling your articles or books or poems or whatever—you certainly need to understand how things work if you’re going it alone, say, as a freelancer. You can be less worried about the sausage-making if you work for a large company that focuses on that.

CL: Quality or quantity in regards to online publications?

BG: Maybe I’m naïve, but I think you ought to always try to do your best work. That said, sometimes you have more time or freedom or resources than you do other times. Especially when you’re just getting started, you want to get your name out there, and the more it’s out there, the more likely you are to attract readers, viewers, sources, hiring editors. Still, crappy work is crappy work, and won’t help you regardless of how much of it is out there.

CL: In your own words, what significance does “mystery” have as a genre?

BG: I am fond of arguing that most novels are essentially mysteries in which the writer poses a question that the book seeks to answer. Holden Caulfield is in insane asylum. How and why did he wind up there? Salinger tells us in the rest of that book. As a genre, though, mystery attracts huge numbers of readers. Along with their close cousins, thriller, mysteries are by far the most popular books. Alas, some are formulaic, predictable, unimaginative. But the best ones are literature: Lehane, Mosely, Chandler, Hammett. Mystic River is one of the best novels I’ve ever read (and a lot better than some of the navel-gazing drivel that the elite “literature” reviewers love so much).

CL: Who are the best writers out right now, and why?

BG: Again, I don’t read enough for such superlatives, but in addition to Harbach’s novel, books by contemporary authors I’ve enjoyed in the past year or so include Frank Bills’s short-story collection, Crimes in Southern Indiana; Emma Cline’s The Girls; and my pal Doyle’s semi-autobiographical Chicago.

CL: Why do you write?

BG: You might as well ask why I love my wife and kids, why I get up in the morning, why I eat. It’s what makes me me.

CL: Donald Trump is our president. What is next for America? What is next for Bryan Gruley?

BG: I won’t hazard any specific guesses, except this one, which has been played out in history time and again: the party in power will overplay its hand and the political pendulum will swing back in the other direction. As for me, I’m finishing the rewrite of a novel called The Last of Danny, about the kidnapping of an autistic boy. Wish me luck persuading a publisher to take it on.

Cody Lee has no sense of humor, and hates everyone. He’s smart, too.

June 12, 2017