A New Narrative: Artists Exploring Blackness

Three Columbia College Chicago alumni discuss how they explore contemporary black life through their visual art.

There is no one true definition of blackness in America today. As the country continues to diversify and change at a rapid pace, so too does our understanding of what it means to be black. Artists in particular continue to challenge our perceptions and understandings of blackness by creating work that speaks to their own lived experiences. They are telling new narratives of blackness, ones that center the minds, bodies, and environments of black people typically ignored. Here, three Columbia College Chicago alumni—Ervin A. Johnson ’12, Krista Franklin MFA ’13, and Tonika Johnson ’03—discuss how they explore contemporary black life through their visual art. – Britt Julious

Ervin A. Johnson

“I CAN’T SPEAK FOR ALL ARTISTS, but I know for myself personally, I use my work to figure out how I want to exist and how I see myself,” says Ervin A. Johnson ’12.

The multidisciplinary artist—best known for his deconstructed photo collages and colorful, abstract expressionist, mixed-media paintings—creates work that tries to disrupt and change the perceptions of black men and women. Specifically, Johnson is interested in depicting the femininity and humanity in the black body, two things that historically have been denied or ignored.

“I want to normalize how I see myself and how my friends present themselves to me,” Johnson says. “And then on a larger scale, how they present themselves to other people.”

Johnson cites his time at Columbia as a catalyst in the development of his artistic practice. At Columbia, Johnson learned the logistics of photography and experimented with painting. In 2016, Johnson also received the Diane Dammeyer Fellowship in Photographic Arts and Social Justice through Columbia and anti-poverty organization Heartland Alliance—which included a $25,000 stipend to create socially conscious work.

An art history class introduced him to the philosopher Walter Benjamin and his concepts of art in the age of mass reproduction. “The notion of reproduction is important just because I’m trying to alter the perception of black men and women,” says Johnson.

As a photographer, Johnson creates mass reproductions of images of black people. Later, he cuts, paints over, strips, and reconfigures those photographs to create entirely new works. Johnson pulls back on the reconstruction, he says, when the original humanity in the image is no longer there. Johnson is renegotiating how people understand and interpret black bodies and their existence in this world. His work—large and evocative—tells a new narrative of blackness.

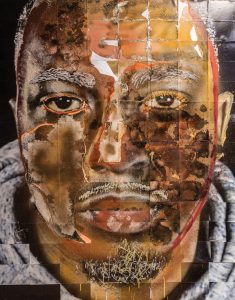

“Billy,” #InHonor series, photo-based mixed media, 2016—Johnson’s ongoing mixed-media project #InHonor began in response to the killings of Trayvon Martin and Eric Garner and will continue “as long as lives are lost from racism and police brutality.”

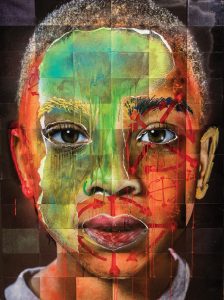

“Nicole,” #InHonor series, photo-based mixed media, 2016—The larger-than-life images portray various types of blackness and encompass different skin tones, genders, races, and sexualities

“George,” #InHonor series, photo-based mixed media, 2016—Johnson photographs his subjects in Chicago, Atlanta, and New York City. He enlarges their portraits and recreates “skin” using paint, glitter, paper, and other media.

“Victor,” #InHonor series, photo-based mixed media, 2016—Johnson’s aggressive, hands-on process of creating his #InHonor portraits (including occasionally ripping the canvas) reflects the violence of police brutality and American society’s hostility toward black people.

KRISTA FRANKLIN

KRISTA FRANKLIN

“I DECIDED TO GO BACK to school because I wanted to have more tools in my toolbox,” says Krista Franklin MFA ’13.

Prior to entering Columbia, Franklin worked almost exclusively as a writer and poet. She began making mixed-media collages to work through writer’s block. Although she never obtained a formal art education as an undergraduate (Franklin got her degree in Pan-African Studies), she took to the collage medium. Franklin often centers photographic images of black women or celebrated cultural figures like Run DMC in her work while playing with material as varied as magazine cutouts and craft ribbon. Soon, her collages found popularity among her peers.

“It was really the poets in my life—the writers in my life—who realized what I was doing visually and inspired me to put it in the public eye,” she says.

Her time at Columbia in the Center for Book and Paper Arts allowed her to master her new creative outlet in collage. “Let me think of this as a craft, as an art practice, and let me consolidate it and put it in the framework of what I already do with my writing as an interdisciplinary artist,” she says about her decision to go back to school.

Many of her pieces are inspired by her deep love of science fiction and fantasy. Franklin cites the science-fiction writer Octavia Butler as one of her biggest influences. Butler is one of the best-known African American writers of the genre. Franklin says her 2013 project, The Two Thousand & Thirteen Narrative(s) of Naima Brown, about a girl changeling on the precipice of young adulthood, was inspired by Butler’s work.

Like Butler before her, Franklin is interested in exploring the ways in which we find solace in our world and in the work we create. “How do we find peace in this chaotic landscape that we’re living in?” she asks. “What are the mechanisms and tools that we can use to find peace?”

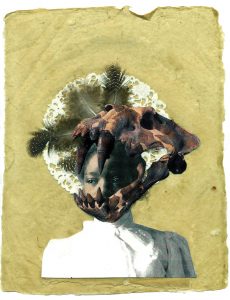

We Wear the Mask II, collage on handmade paper, 2014—Franklin’s work emerges from her interests in science fiction, surrealism, fantasy, mythmaking, and black identity.

To the Limit To the Wall, album covers in handmade paper, 2016—Many consider Franklin’s work to be AfroFuturist: an aesthetic combining history, fantasy, science fiction, magical realism, and Afrocentrism.

We Wear the Mask VIII, collage on handmade paper, 2014—We Wear the Mask investigates negative perceptions of women by fusing female bodies with parts of animals, plants, and other organic entities.

We Wear the Mask I, collage on handmade paper, 2014—The series inspiration comes from 19th-century poet Paul Laurence Dunbar’s poem “We Wear the Mask,” which explores surviving in the world as a person of color.

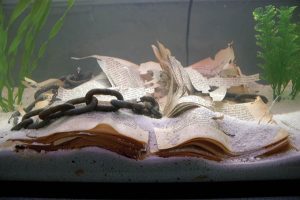

…voyage whose chartings are unlove, altered book and mixed media in aquarium, 2013—In this case, her alteration and implantation of a book into an aquarium transforms an existing work into a new installation. The title pays homage to Robert Hayden’s poem “Middle Passage.”

Tonika Johnson

Tonika Johnson

“I KNOW HOW TO TELL A STORY, and I know that because of Columbia and the resources it provided,” says photographer Tonika Johnson ’03.

At Columbia, Johnson studied journalism and photojournalism. Her work focuses on capturing neighborhoods of Chicago that are typically only seen in one light. Johnson grew up in the city, largely in the Englewood neighborhood and on the North Side of the city. She began photographing her community while in high school.

Looking through her images, she realized the photographs she took were different than the typical depictions of her neighborhood. As an artist, Johnson aims to dismantle stereotypes of the city she knows and loves.

Social justice and art go hand in hand for her. “Photography is my form of social justice to shatter negative stereotypes,” she says. “I just really love being able to cut out a moment from a scene. I was able to perfect my vision of what I want to capture at Columbia.” The school taught her the fundamentals and technical aspects of working a camera and reporting that she continues to carry with her not only as an artist and a photographer, but as a storyteller.

In her most recent exhibition, Everyday Rituals, Johnson bridges the gap between the black secular and the divine. Churches, hair, self-care, cooking: These fundamental elements and ideas structure the project. In this exhibition, Johnson sheds light on the routines, rituals, and environments that encompass contemporary black life and does so through new mediums like film. She is both documenting the everyday and elevating it from its origins to fine art worthy of a second look.

“With the political climate of today, especially with Chicago being a focus and the neighborhood I photograph in being a kind of reference, I want people to find a space of healing and beauty and to be able to appreciate this city and the diversity that still exists,” she says.

Rob and Lakeisha In Love—A young couple walks hand in hand after purchasing a bag of snacks from the corner store on 66th and Morgan streets.