1961-1992: Renewal and Expansion

The Columbia of the ’60s was the ultimate underdog. With flailing enrollment and few resources, the school could have folded. Instead, President Mike Alexandroff turned it into a thriving, accredited college with a reputation for breaking the mold of what arts education could be.

When Mirron “Mike” Alexandroff took the reins as president in 1961, Columbia was at a crossroads. The massive influx of GI Bill students virtually ceased after the war in Korea, and enrollment was less than 200 students. Though the college formally separated from Pestalozzi Froebel Teachers College (PFTC) in 1944, the two schools still shared many resources.

Herman Hofer Hegner, still the head of PFTC, was concerned about Columbia’s instability and in 1963 notified Alexandroff that PFTC would relocate to a new campus. All jointly shared staff, equipment and curricula accompanied PFTC, leaving Columbia with few possessions, a reduced staff, a limited curriculum and too much physical space.

With no endowments and an unsustainable business model, the future of the college was in jeopardy. “If I had been sensible,” Alexandroff said in An Oral History of Columbia College, “we would have just folded it up and walked away.”

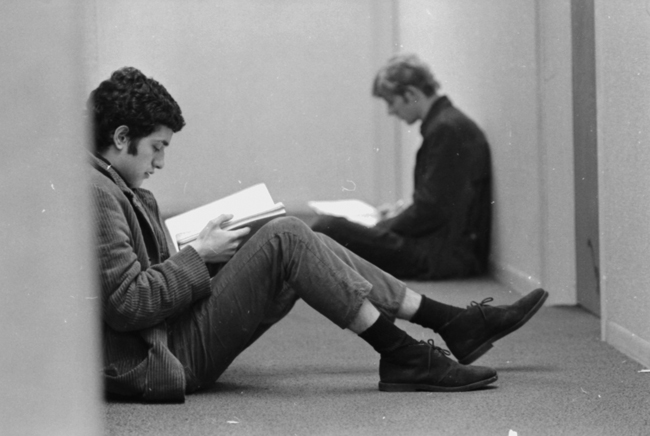

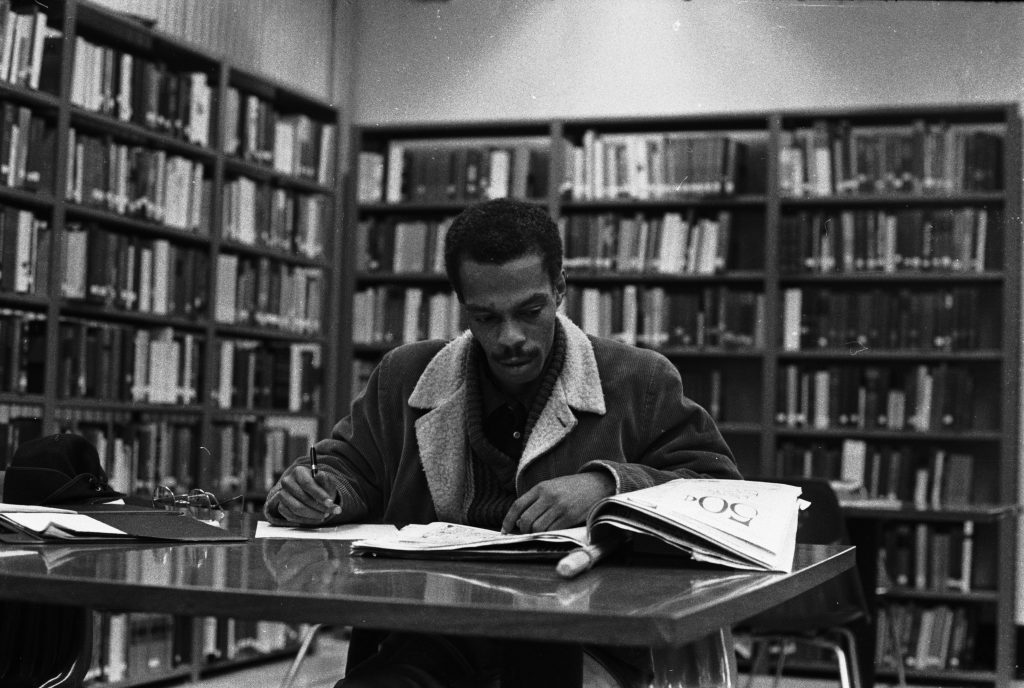

Instead, he crafted a new vision for the college that played on its strengths. The urban location was labeled as a “sidewalk campus.” He enlisted local media professionals as instructors, focused the curriculum on the arts and media, and pushed for higher minority enrollment. Most importantly, he focused on an open admissions policy that allowed more students to enroll—including students who didn’t always fit into typical higher education parameters. The formula worked: Between 1964 and 1974, enrollment increased from less than 200 to more than 1,000 students, 22 percent of whom were African American.

Between 1964 and 1974, enrollment increased from less than 200 to more than 1,000 students.

To meet the needs of the growing school, the college began renting its headquarters at 600 S. Michigan Ave. in the mid-1970s, establishing its campus in the South Loop. Marketing materials of the time put it like this: “Columbia is at the center of the city and the whole city is Columbia’s campus.” Alexandroff thought the building would provide the school with all the room for growth it would need for decades to come. Less than 10 years later, the college expanded yet again with two more buildings: 623 S. Wabash Ave. and the Theatre Center at 72 E. 11th St.

Alexandroff saw Columbia as a college that couldn’t—and shouldn’t—compete with more traditional schools. Columbia became a pioneer in combining arts and media curricula for a unique and relevant education.

Columbia emphasized the combination of theory and practice, with a focus on career-driven programs rather than classical training. However, Alexandroff was also concerned with legitimacy: He wanted to leave behind the semblance of a “trade school” and offer a robust, if nontraditional, liberal arts education. In an earlier era, the regional accrediting body, the North Central Association (NCA), “utterly dismissed the possibility of accrediting anything that was unlike the most conventional colleges,” he said. But the cultural revolution of the 1960s changed the landscape of higher education and eventually, the NCA warmed up to Columbia. After building a library and undergoing a years-long review process that Alexandroff characterized as “a hell of a struggle,” the college was fully accredited in 1974. The graduate division, created in 1981, was awarded full accreditation just three years after its founding.

The ’80s also saw the growth of Columbia’s flagship programs in radio and television. WCRX, Columbia’s student-run radio station, hit the airwaves in 1982. In 1985, the school acquired a Mobile Broadcasting Unit that functioned as a classroom on wheels, training students to broadcast on location—and drawing a crowd whenever students set up equipment on its rooftop.

By the time Alexandroff retired in 1992, Columbia had grown to more than 7,000 students. The college—now wholly independent, accredited and gaining a reputation as a diverse, dynamic training ground for arts and media careers—was ready to take on the 21st century.

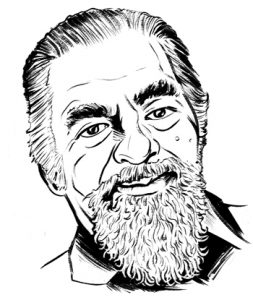

Mirron “Mike” Alexandroff: President 1961-1992

Following in the footsteps of his father Norman, Mirron “Mike” Alexandroff used his presidency to usher Columbia through a period of growth and transformation. Before stepping up as president, Alexandroff served as a sergeant in the U.S. Army in the South Pacific during World War II. When he came home, he took a position as a psychologist in Columbia’s Veterans Administration Guidance and Research Center, later becoming its manager. During the ’50s, when his father relocated to California to oversee Columbia College Los Angeles, Mike took on the college’s day-today operations as acting president.

Following in the footsteps of his father Norman, Mirron “Mike” Alexandroff used his presidency to usher Columbia through a period of growth and transformation. Before stepping up as president, Alexandroff served as a sergeant in the U.S. Army in the South Pacific during World War II. When he came home, he took a position as a psychologist in Columbia’s Veterans Administration Guidance and Research Center, later becoming its manager. During the ’50s, when his father relocated to California to oversee Columbia College Los Angeles, Mike took on the college’s day-today operations as acting president.

After Norman Alexandroff died in 1960, the board appointed Mike as president in 1961. At the time, the tuition-driven college struggled with low enrollment and few resources. Inspired by his father’s own reinvention of Columbia in the ’40s, Alexandroff rebuilt the school for a new generation. He enlisted local media professionals as instructors, focused curriculum on arts and media, and championed an open admissions policy. Under his direction, the college received full accreditation and grew from less than 200 students to more than 7,000.

Alexandroff was active in progressive politics and civic life, receiving numerous awards for achievements in education and social justice. In 1961, he married Columbia’s registrar, Jane Legnard, and had a son, Norman. The couple threw parties in their home for faculty, staff and even students, building up a tight-knit Columbia community that felt like a family, according to faculty and staff from that time.

After Alexandroff retired in 1992, the city designated the block of Harrison Street between Michigan and Wabash avenues as “Mirron ‘Mike’ Alexandroff Way.” After Jane died in 1996, Alexandroff wrote his memoir, A Different Drummer, which today serves as a record of the day-to-day interactions and colorful characters from this formative stretch of Columbia’s history.

The Door Is Open

How an open admissions policy created today’s Columbia College Chicago

Though the two schools separated in 1944, Columbia and Pestalozzi Froebel Teachers College continued sharing resources until 1963. Stepping up as president in 1961, during this period of transition, Mike Alexandroff was forced to rethink the ways Columbia defined itself.

Although Columbia had always filled a unique niche, Alexandroff wanted to revamp the college’s mission and the institution’s place in the higher education landscape of the ’60s. “It was clear that Columbia could not prosper as a mild alternative to customary institutions,” he wrote in his memoir, A Different Drummer. “What was necessary instead was that Columbia become genuinely experimental and innovative in all respects.”

So the college instituted an open admissions policy that championed inclusivity over exclusivity, opening the doors of higher education to those passionate about studying arts and media.

The policy’s origins were both ideological and practical, according to Alexandroff. Reinvention included recruiting minority students from inner-city schools who were overlooked by other institutions. Alexandroff envisioned Columbia as “a low-cost specialized college that practiced open admissions and assembled an accomplished faculty … who could inspire students to liberate the best of themselves.”

Open enrollment made a huge impact: Between 1964 and 1974, the number of enrolled students jumped from less than 200 to more than 1,000. By 1974, Columbia was finally accredited and on a path to financial viability. Inclusivity was no longer absolutely necessary to the college’s survival, yet Alexandroff became more committed than ever to the idea.

“I think in a philosophical sense, I’d been a progressive my whole life,” he said in An Oral History of Columbia College. “But by ’66, I was beginning to have a kind of developed philosophy about the institution, and certainly a vigorous opposition to the elitist ideas that had governed higher education.”

Today, Columbia continues to build on Alexandroff’s progressive philosophies, marking it as a place where commitment to an artistic career is of the utmost importance. “We’re going to be a school that shows you can be great without being elite,” said President Kwang-Wu Kim.

Powerful Professors

Illustrious faculty members molded the college into a media powerhouse

In the 1960s and ’70s, President Mike Alexandroff aggressively campaigned to bring respected media and arts professionals to the college as faculty members and department chairs. Unlike other colleges, Columbia did not recruit instructors based on their academic credentials alone, but rather their professional accomplishments, industry knowledge and teaching ability.

When Columbia ceased sharing resources with Pestalozzi Froebel Teachers College, it was a small college with a nearly nonexistent budget; exceptional faculty became its key to survival. In An Oral History of Columbia College, Alexandroff said departments were built around a handful of instructors who had free reign: “I wanted to get these remarkable people, and give them a start and get out of their way.”

Prolific Chicago radio announcer Al Parker became chair of the Radio Department in 1957. There, he brought in faculty from major Chicago stations, who in turn hired Columbia alumni. Alexandroff wrote in his history of the college that Parker and the radio faculty “were literally an employment agency for the college’s broadcasting students.”

The chairs of the Television and Music departments—Thaine Lyman and Bill Russo, respectively—were equally crucial in building a strong reputation for their programs and attracting national attention to Columbia in the 1960s. Meanwhile, much-lauded modern dancer Shirley Mordine headed the Dance Department and opened the Dance Center in 1970 as Chicago’s only venue dedicated exclusively to contemporary dance, according to Alexandroff, which attracted innovative dancers and companies from around the world.

During this era, the part-time faculty roster was also filled with movers and shakers. Film critic Roger Ebert taught at Columbia in the early ’70s, and renowned journalist and author Studs Terkel led classes in jazz and folk music and later taught at Columbia’s Community Media Workshop. Terkel retained an affinity for Columbia throughout his life, calling it the college “for working-class kids who never had the dream.” From 1963 to 1969, Pulitzer Prize-winning poet Gwendolyn Brooks taught and directed the poetry curriculum at Columbia. She recalls in her autobiography that Alexandroff told her, “Take it outdoors. Take it to a restaurant. … Do absolutely anything you want with it. Anything!”

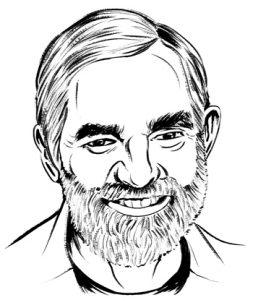

Bill Russo: Renegade Thespian

In 1965, accomplished musician, composer and conductor Bill Russo became a full-time faculty member at Columbia. Returning to his hometown of Chicago after spending time in New York City and London, he founded Columbia’s Music Department and became director of the Center for New Music. Three years into his tenure, he founded the Free Theater, an avant-garde company focusing on rock musicals—and a project that would shape both Columbia and the whole Chicago theatre scene.

In 1965, accomplished musician, composer and conductor Bill Russo became a full-time faculty member at Columbia. Returning to his hometown of Chicago after spending time in New York City and London, he founded Columbia’s Music Department and became director of the Center for New Music. Three years into his tenure, he founded the Free Theater, an avant-garde company focusing on rock musicals—and a project that would shape both Columbia and the whole Chicago theatre scene.

From its launch in 1968, Russo’s Free Theater channeled the era’s wild, creative, politically charged energy. Productions translated classic stories like Antigone and Aesop’s Fables into rock operas that also served as commentary about the Vietnam War, the Civil Rights movement and other topics of the day. Shows were always free, which made them accessible to everyone. (At the end of each show, the audience passed a hat for donations.)

Columbia students worked alongside community members and professional musicians on every part of the productions, from acting to sewing costumes to sweeping the stage. Some shows became cult-popular, with audience members returning again and again in costumes to match. In fact, the Free Theater’s popularity spawned sister companies in Baltimore and San Francisco.

Senior Theatre lecturer Albert “Bill” Williams (BA ’73) came to Columbia to study under Russo after seeing a Free Theater show. He remembers the multimedia aspect of productions, which in those days meant projecting 8 mm films onto bed sheets hung across the stage. “It was very funky and rough edged,” he said. “It had a very handmade, low-tech feel.” A seminal company in the Off-Loop theatre movement, the Free Theater was a precursor to modern Chicago companies like Steppenwolf and Lookingglass Theatre.

Gwendolyn Brooks: Legendary Poet

Chicagoan Gwendolyn Brooks achieved many firsts as an African-American poet. The first black author to win a Pulitzer Prize, serve as poetry consultant to the Library of Congress and be named poet laureate of Illinois, Brooks also received Columbia’s first honorary degree in 1964.

Chicagoan Gwendolyn Brooks achieved many firsts as an African-American poet. The first black author to win a Pulitzer Prize, serve as poetry consultant to the Library of Congress and be named poet laureate of Illinois, Brooks also received Columbia’s first honorary degree in 1964.

Already a Pulitzer winner when she arrived at Columbia, Brooks taught poetry and directed the poetry curriculum from 1963 to 1969. A poet of and for the people, specifically the black urban poor, Brooks raised voices in collections like A Street in Bronzeville, Annie Allen and The Bean Eaters. Today, she’s still remembered as the “Patron Saint of Bronzeville” and a huge force in Chicago poetry. Her 1991 poem “Speech to the Young” includes this advice: “Live not for battles won. / Live not for the-end-of-the-song. / Live in the along.”

Shirley Mordine: Contemporary Dancemaker

For three decades, Shirley Mordine built and directed Columbia’s Dance Center, one of few centers in Chicago devoted exclusively to contemporary dance, and shaped the city’s now-thriving dance scene.

For three decades, Shirley Mordine built and directed Columbia’s Dance Center, one of few centers in Chicago devoted exclusively to contemporary dance, and shaped the city’s now-thriving dance scene.

“There was nothing else going on in dance in Chicago,” Mordine told Chicago Artists Resource of the scene she entered in 1969. “Maybe a few isolated teachers here and there, but [virtually] nothing that had any sort of foundation or organization.”

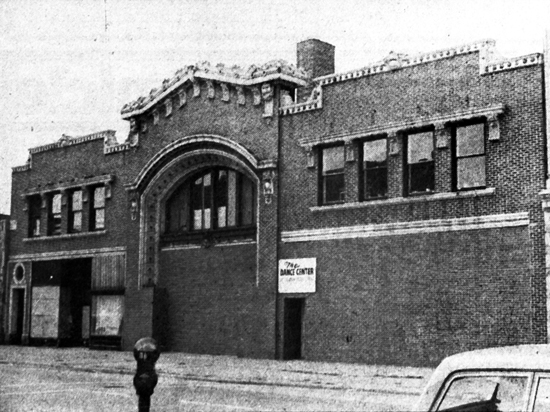

Mordine began teaching in Columbia’s Theatre Department, but soon laid the foundation for a separate Dance Department. By 1972, the Dance Center moved into 4730 N. Sheridan Road in Chicago’s Uptown neighborhood and began presenting work from outside companies—including Hubbard Street Dance, now one of Chicago’s leading contemporary dance companies.

The creative groundswell quickly led to greater support, larger shows, and a $100,000 MacArthur grant to boost production and technical levels. Now a multifaceted and renowned institution that acts as a teaching, learning and performing arts vehicle, the Dance Center continues to receive national recognition and host companies from around the world.

By spearheading the Dance Center, Mordine helped transform Columbia into the powerhouse arts school it is today. She earned the college’s Presidential Medal for Distinguished Service in 1999.

Sheldon Patinkin: Chicago’s Theatre Giant

Saturday Night Live star Aidy Bryant (BA ’09). Award-winning theatre director David Cromer (’86). Steppenwolf Theatre Artistic Director Anna Shapiro (BA ’90). The late and legendary Sheldon Patinkin taught hundreds of students as chair of Columbia’s Theatre Department from 1980 to 2009. The alumni he influenced went on to shape theatre in Chicago and beyond.

Saturday Night Live star Aidy Bryant (BA ’09). Award-winning theatre director David Cromer (’86). Steppenwolf Theatre Artistic Director Anna Shapiro (BA ’90). The late and legendary Sheldon Patinkin taught hundreds of students as chair of Columbia’s Theatre Department from 1980 to 2009. The alumni he influenced went on to shape theatre in Chicago and beyond.

Patinkin began his career as a founding member of The Second City and its precursor ensemble, The Compass Players. He helped sculpt the city’s theatrical landscape by providing artistic guidance for renowned performance companies, including Second City and Steppenwolf Theatre. In 1980, Patinkin brought his award-winning directing into Columbia’s classrooms when he was tapped to lead the school’s Theatre Department, growing the department into one of the country’s largest. He used his unique relationship with Second City to develop Columbia’s BA in Comedy Writing and Performance—the first degree of its kind in the nation.

“I don’t think there is anybody practicing in Chicago today that hasn’t been helped by Sheldon, and so many theater people have stayed here, or returned here, because of the life he modeled,” Shapiro told The New York Times.

Today, he is remembered on campus through the Sheldon Patinkin Award, which provides a senior Theatre student with a cash stipend to aid in their professional journey.

Jacob Caref: Columbia’s Craftsman

When people remember the building of Columbia’s foundation, they don’t usually mean it literally—unless they’re talking about Jacob Caref. A pipe fitter by trade and a carpenter out of necessity, Caref was a virtual one-man shop at Columbia throughout the 1960s.

When people remember the building of Columbia’s foundation, they don’t usually mean it literally—unless they’re talking about Jacob Caref. A pipe fitter by trade and a carpenter out of necessity, Caref was a virtual one-man shop at Columbia throughout the 1960s.

As a staff member, he matched the “can do” spirit of hardworking faculty and eager students. In his earliest days, with a shoestring budget and the occasional student helper, Caref built backdrops in a television studio and darkrooms for photography students. Later, he constructed sets and stages for the Theatre Department and a new Dance Center that contractors might have charged thousands of dollars to build.

A Jewish-Polish immigrant whose entire family was killed during World War II, Caref said he felt welcomed into President Mike Alexandroff’s family. He even spent several Thanksgiving dinners with the Alexandroffs.

In an oral history published in the late 1990s, Caref described the Columbia atmosphere of three decades earlier, when the population consisted of just a few hundred students and a host of part-time instructors spread throughout the city. “I am a carpenter, a builder,” he said. “What people don’t see in a house is the foundation. The same thing [is true] in Columbia College. People don’t see [the] type of foundation, but it is very strong.”

Then and Now: Liberals Arts and Sciences Core

Then: Columbia strengthened its liberal arts and sciences (LAS) core in the early 1960s, requiring nearly 50 percent of a student’s coursework to be completed under the LAS umbrella. However, students were able to take these courses as electives “when such studies [had] relevance to the student’s life and career,” said President Mike Alexandroff.

Now: All undergraduate students complete an LAS core curriculum, with many science and mathematics courses designed specifically for artistic disciplines. Courses include Chemistry of Art and Color, Physics for Filmmakers, and the Science of Acoustics.

Then and Now: Student Media

Then: Since its earliest days, Columbia has encouraged students to jump straight into their artistic practice. The birth of many student media outlets in the late ’70s and early ’80s helped hone countless student voices. Hair Trigger, a compilation of undergraduate and graduate fiction, launched in 1977. In 1978, Columbia’s student newspaper, the CC Writer, was replaced by the weekly (and now award-winning) Columbia Chronicle. In 1982, student radio station WCRX went on air, sharing music and public affairs programming from departments across the college. That year also saw the launch of Columbia’s record label, AEMMP Records, managed by Arts, Entertainment and Media Management (AEMM, now Business and Entrepreneurship) students.

Now: All of these student outlets are still going strong, with more organizations added to their ranks over the years. Creative Writing students edit and produce the nationally distributed Columbia Poetry Review and the nonfiction journals South Loop Review and Punctuate. Journalism students run citizen-reporter sites ChicagoTalks.org and AustinTalks.org, as well as the biannual magazine Echo. Television students and volunteers from all across the college run Frequency TV, producing entertainment and news programming with state-of-the-art technology (including a mobile production truck).

Home Sweet Home

Where Columbia lived starting in 1963

540 N. Lake Shore Drive

Occupied: 1963–1977

Housed: Entire campus, including studio space, library, classrooms, a fully equipped television station and a darkroom

Trivia: Columbia enrolled approximately 1,800 students while at this location, which is across the street from what is now called Navy Pier.

4730 N. Sheridan Road

Occupied: 1972–2000

Housed: Dance Center

Trivia: This was the only building Columbia actually owned in the early 1970s.

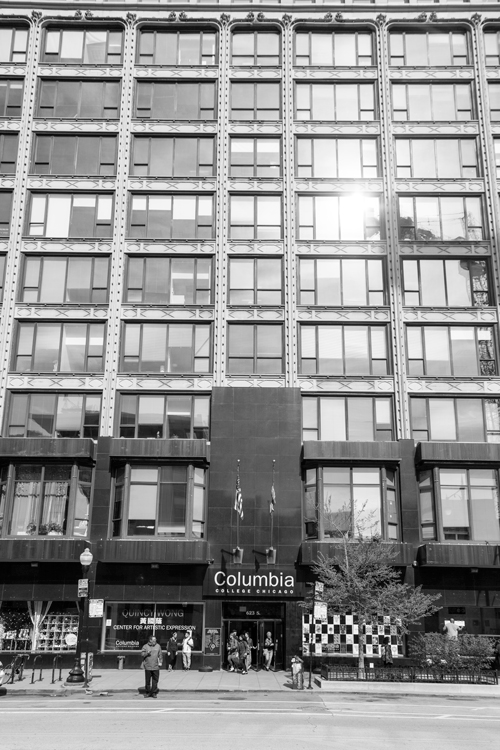

Alexandroff Campus Center, 600 S. Michigan Ave.

Occupied: 1977–present

Houses: Administrative operations, classrooms, darkrooms, TV studios, film/video editing facilities, Museum of Contemporary Photography

Trivia: Designed by Christian Eckstorm in 1906–1907 for the International Harvester Co., one of the nation’s leading industrial corporations. When Columbia’s expanding population needed more space, this building served as the college’s first permanent home in the South Loop.

Getz Theater, 72 E. 11th St.

Occupied: 1980–present

Houses: Theater spaces, classrooms

Trivia: Designed in 1929 by Holabird & Root, one of Chicago’s leading architectural firms. The building was previously used by the Chicago Women’s Club to rally for voting rights.

623 S. Wabash Ave.

Occupied: 1983–present

Houses: Classrooms, academic offices, science laboratories, art studios, stage and costume design workshops, public gallery spaces

Trivia: Designed in 1895 by Solon S. Beman for the Studebaker Brothers Carriage Company. Later tenants included the Brunswick Company, makers of wood furnishings and built-in furniture for libraries, universities and a variety of other facilities.

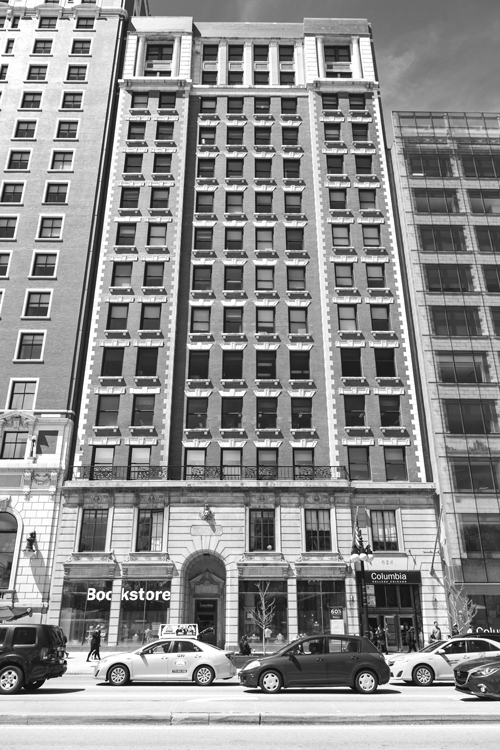

624 S. Michigan Ave.

Occupied: 1990–present

Houses: Five-story library, classrooms, departmental offices, student and faculty lounges, the bookstore

Trivia: When it was constructed in 1908, the building was only seven stories tall. Seven additional stories were added in 1922.

Alumni Spotlights

1960s: Bob McNamara

For four decades, family rooms all over America welcomed Bob McNamara (BA ’66) onto their screens. The five-time Emmy Award-winning journalist filed reports for the CBS Evening News, The Early Show, 48 Hours and CBS Sunday Morning. And he credits Columbia with getting him there.

At Columbia, McNamara studied under professors like Pulitzer Prize-winning writer Tom Fitzpatrick and legendary radio instructor Al Parker. In 2010, Columbia honored McNamara as one of three Alumni of the Year.

McNamara’s resume reads like a lesson in U.S. history, which he helped to document on a nightly basis. He covered five school shootings, several hurricanes and the Oklahoma City bombing, to name a few historical events. Through it all, human interest stories remained his favorite to report.

Through hundreds of broadcasts—from the Lebanese Civil War in the 1970s to the 2003 Columbia shuttle disaster—McNamara brought the world home to his viewers. And many of those stories will never be forgotten.

1970s: Melissa Ann Pinney

In the first photo of Guggenheim-winning photographer Melissa Ann Pinney’s (BA ’77) series Girl Ascending, a young girl hangs by one hand on a chain-link fence, suspended against a dusty baseball field; she looks like she can fly. Throughout a photography career that spans four decades, Pinney captures countless moments of girlhood rituals and the transition from adolescence to adulthood.

Many of her projects, like Regarding Emma and Cellar Door, revolve around her daughter. Her photographs have been exhibited at the Art Institute of Chicago, the Museum of Modern Art and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City, and the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, among many others. In 2015, HarperCollins released Pinney’s latest book, TWO, a collaboration with acclaimed author Ann Patchett. The book pairs Pinney’s photos of twosomes—from couples in love to a couple of teacups—with essays from writers including Barbara Kingsolver, Elizabeth Gilbert and Susan Orlean. Pinney’s career has blossomed since she graduated in 1977, but she’s stayed close to her alma mater— she’s taught in the Photography Department since 1985.

1980s: Marlon West

Pocahontas, Mulan, The Princess and the Frog—if it’s a Disney animated classic produced after 1990, chances are animator Marlon West (BA ’85) had a hand in the production. West started at Disney creating effects for the blockbuster The Lion King. In 2013, he worked as head of effects animation on megahit Frozen, which won the Academy Award for Best Animated Feature.

Pocahontas, Mulan, The Princess and the Frog—if it’s a Disney animated classic produced after 1990, chances are animator Marlon West (BA ’85) had a hand in the production. West started at Disney creating effects for the blockbuster The Lion King. In 2013, he worked as head of effects animation on megahit Frozen, which won the Academy Award for Best Animated Feature.

After graduating with an animation degree and working briefly in the Chicago film industry, West headed to Los Angeles. West still remembers what inspired it all: the first time he saw a photograph of legendary animator Willis O’Brien working on The Lost World. “To my second-grade mind, this was a man who had a gig where he could bring his toys to work,” he said. “That’s what I wanted to do.”

More Notable Alumni

Scott Adsit (’87)

Actor (30 Rock, Big Hero 6)

Paul Broucek (BA ’74)

President, Music, Warner Brothers Pictures

David Cromer (’86)

Jeff, Obie and Lucille Lortel Award-winning theatre director, 2010 MacArthur Fellow

Michael Goi (BA ’80)

Cinematographer (American Horror Story, Glee, The Mentalist), board member and former president of American Society of Cinematographers

Janusz Kaminski (BA ’87)

Two-time Academy Award-winning cinematographer (Saving Private Ryan, Schindler’s List)

Parisa Khosravi (BA ’87)

Former senior vice president of international newsgathering and global relations, CNN Worldwide

Steve Pink (’86)

Director (Hot Tub Time Machine, Accepted), writer (Grosse Pointe Blank, High Fidelity)

Cynthia Pushek (BA ’87)

Cinematographer (Revenge, Brothers & Sisters)

Andy Richter (’88)

Writer, actor, announcer (Conan)

Karine Saporta (BA ’72)

Photographer, filmmaker, choreographer, one of the most prominent figures in French dance

Therese Sherman (BA ’90)

Emmy-nominated cinematographer (Wipeout, Fear Factor, Little Man)

Nana Shineflug (MA ’86)

Dancer, owner and founder of The Chicago Moving Company

Bob Sirott (BA ’71)

Radio host, WGN-AM Chicago

Robert Teitel (BA ’90)

Producer (Men of Honor, Barbershop, Notorious)

Ruth Thorne-Thomsen (BA ’74)

Surrealist photographer with work exhibited in the Art Institute of Chicago and the Musee d’Arles in France

George Tillman Jr. (BA ’91)

Director (Men of Honor, The Longest Ride), producer (Barbershop)