1944-1960: Postwar Boom

In the mid-20th century, Columbia became a hub for veterans eager to enter the rapidly growing fields of radio and television. Columbia adapted to the demand for broadcast training, laying the foundation for today’s media arts college.

In 1944, Columbia formally separated from Pestalozzi Froebel Teachers College. Radio Department Chair Norman Alexandroff took over as president, and the school reinvented itself yet again. Alexandroff, a Jewish immigrant from Russia who came to the U.S. with $5 in his pocket, knew about reinvention. Under his tenure, Columbia expanded both its student body and its programs, bolstered by a postwar education boom from the GI Bill.

The GI Bill, signed into law in 1944, provided education, loans and access to psychiatric services to millions who served in World War II. It was legislation that shaped America, creating a robust middle class. It also shaped Columbia, adding an influx of male students to the traditionally female college and creating a demand for radio and television programs.

At the peak of the GI Bill era, veterans represented 49 percent of college admissions nationwide, and Alexandroff lobbied for a chance to make Columbia a destination for returning servicemen. In 1945, the U.S. government designated Columbia as one of a small number of Veterans Administration Guidance and Research Centers nationwide. The college counseled and provided job training to more than 20,000 vets (not all of whom were Columbia students) over the next five years.

The school’s emphasis on broadcast media made it a popular option among young vets, who were buoyed by postwar optimism and captivated by new technology.

The college added television classes to the curriculum in 1945—just a few years after the first NBC telecasts aired. The school’s emphasis on broadcast media made it a popular option among young vets, who were buoyed by postwar optimism and captivated by new technology. Increased enrollment also led to the creation of the Journalism Department and the Advertising and Business Department. (These subjects had previously been taught in radio and TV courses.)

In 1947, Columbia established a new method of teaching. The workshop method, still a fixture in Columbia classrooms today, teaches through the hands-on, collaborative efforts of a group of students working on a common project, such as a TV show or film that employs students as writers, camera operators, actors and more. This teaching method solidified Columbia’s integration of theory and practice and set the tone for the burgeoning arts and media college that would emerge in the 1960s.

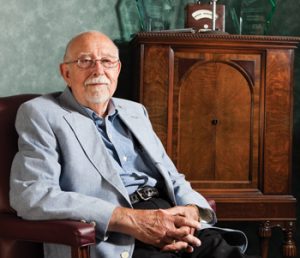

Norman Alexandroff: President 1944-1960

Nime Kulczinsky was born in 1887 in Kishinev, Russia. He never attended formal school but received tutoring from his older brother. Russia was not safe for progressive-thinking Jewish men at the time, so Kulczinsky left for America in 1902. He later changed his name to Norman Alexandroff.

Nime Kulczinsky was born in 1887 in Kishinev, Russia. He never attended formal school but received tutoring from his older brother. Russia was not safe for progressive-thinking Jewish men at the time, so Kulczinsky left for America in 1902. He later changed his name to Norman Alexandroff.

Alexandroff thrived in his new country. He became fluent in English, an accomplished writer and an in-demand speaker on the national lecture circuit. After obtaining naturalized citizenship in 1912, he worked to promote literacy among immigrants. A few years later, together with William Dean Howells, David Starr Jordan and Jack London, he founded the Literary Association of America and served as its president until 1922. That same year, he married Cherrie Phillips in New York and moved to Chicago.

In the late ’20s, Alexandroff worked in real estate, but when the market crashed in 1929, he tried something completely new: radio. In 1931, he launched a popular radio program, Pages from Life, recounting the adventures of the fictional Mr. Rubin and his Hurry-up Substitute Company, and starred in every role. He later developed the hit show Cavalcade of America, which recounted American history through dramatized accounts of individual heroism. His work caught the ear of Herman Hofer Hegner, who was acting president of Columbia and its sister institution, Pestalozzi Froebel Teachers College (PFTC). In 1934, Hegner recruited Alexandroff to build a new Radio Department, which would house Columbia’s most popular program for decades to come. Alexandroff became vice president of both colleges in 1937.

In 1944, Columbia split from PFTC, and Alexandroff became Columbia’s president. Alexandroff’s efforts to attract veterans— which included co-authoring a study contesting the common claim that all returning soldiers suffered mental trauma that made them unfit for work or higher education— paid off with the establishment of a Veterans Administration Guidance and Research Center at Columbia and skyrocketing enrollment driven by veterans.

Alexandroff thrived in his new country. He became fluent in English, an accomplished writer and an in-demand speaker on the national lecture circuit.

While Columbia has always maintained strong connections to the local community, its history includes some geographically far-flung projects. During the 1950s, Alexandroff relocated to California. He founded another branch of the school, Columbia College Los Angeles, to focus on film and television training and instituted a program for Columbia professors to train Mexican broadcast teachers at Columbia College Panamericano in Mexico City.

Alexandroff served as president of Columbia until his death in 1960 at age 72. His son, Mike Alexandroff, would take over the presidency and steer Columbia in a new direction.

Alumni Spotlights

1940s: Claudio Lazaro

Columbia has long attracted students from all walks of life, but even here, the arrival of an acclaimed Mexican matador was a surprise.

In 1942, 23-year-old bullfighter Claudio Lazaro came to Columbia to study drama, the Chicago Daily Tribune reported. He had previously fought bulls all over Mexico, including in Monterrey, Tampico and Guadalajara. Lazaro told the Tribune that bullfighting “combines the beauty of the ballet with the rough and real path of life.” But despite his love of the sport, the death of a friend led him to America.

Years before, Lazaro had made an oath to a fellow matador that if either died in battle, the other would leave the ring forever.

At Columbia, Lazaro studied drama, served as a correspondent for the Mexican bullfighting newspaper El Redondel and appeared on Chicago’s Spanish-language radio station WHIP each Saturday.

Lazaro told the Tribune that bullfighting “combines the beauty of the ballet with the rough and real path of life.”

1960s: Len Ellis

Len Ellis (BA ’52)—known on the radio as “Uncle Len”—is the longest-running country broadcaster in the Chicago market.

Len Ellis (BA ’52)—known on the radio as “Uncle Len”—is the longest-running country broadcaster in the Chicago market.

While studying in Columbia’s radio program, he worked part time at WJOB, a country station in Hammond, Indiana. He stayed in Hammond after graduating, earning a reputation as a leading country-and-western expert.

Ellis helped form the Country Music Association in 1958, which now has more than 7,000 members and throws an annual festival featuring country music’s biggest names. In 1964, he and his wife started the station WAKE-AM in Valparaiso, Indiana. “If you have your own ideas,” he said, “you need to go on your own.”

His company, Radio One Communications, owned four country radio stations, including WLJE, the highest-rated and longest-running Chicago country station, until 2014.

More Notable Alumni

Peter Berkos (BA ’51)

Sound effects editor; 1976 Academy Award winner for The Hindenburg

Shecky Greene (BA ’47)

Comedian, Las Vegas headliner, guest host for Johnny Carson and Merv Griffin

Howard Mendelsohn (BA ’49)

Radio announcer; public relations executive; founder of Columbia’s Howard Mendelsohn Scholar of Merit Award to support public relations students

Peter Schlesinger (BA ’59)

Producer and former governor of the Television Academy of Arts and Sciences; 18-time Emmy Award winner

Ron Weiner (BA ’52)

Three-time Emmy Award-winning director of The Phil Donahue Show

Beyond Chicago

Columbia opens new entities away from home

In a move historians came to characterize as visionary yet risky, given the college’s limited resources at the time, President Norman Alexandroff opened Columbia College Los Angeles (CCLA) in 1953.

The satellite campus in the heart of southern California’s television and film industry included such notable faculty as Mike Kizzah, a leading sports producer; Melvin Wald, a television and film director; and Ludwig Donath, an Academy Award-winning actor from The Jolson Story who had been blacklisted from the industry for his left-wing ideologies. Self-sufficient by 1959, the school separated from its Chicago counterpart and now operates as Columbia College Hollywood.

Following the successful opening of CCLA, Alexandroff received an opportunity to take the institution’s expertise global.

In 1955, the Mexican and Latin American Association of Radio and Television Broadcasters asked Columbia to train professional radio and television teachers in Mexico City. Guillermo Camarena, creator of Columbia’s first TV installation, and Roberto Kenny, manager of Televicentro’s Channel 1, trained the Mexican teachers at Columbia College Panamericano until 1957. The Mexican and Latin American Association of Radio and Television Broadcasters continued to teach the Columbia method of broadcasting to future generations.

Play Ball!

A brief history of athletics at Columbia

Columbia is hardly known for sports, but back in the 1940s and ’50s, the college had basketball and softball teams. The influx of veterans to campus produced by the GI Bill led to the establishment of athletics at the college. Teams played games off campus in gymnasiums around the city. These mid-century athletics also represent an institutional continuation of the emphasis co-founder Mary Blood placed on physical education and fitness. Today, the college boasts more than a dozen intramural sports teams.

Columbia is hardly known for sports, but back in the 1940s and ’50s, the college had basketball and softball teams. The influx of veterans to campus produced by the GI Bill led to the establishment of athletics at the college. Teams played games off campus in gymnasiums around the city. These mid-century athletics also represent an institutional continuation of the emphasis co-founder Mary Blood placed on physical education and fitness. Today, the college boasts more than a dozen intramural sports teams.

Home Sweet Home

Where Columbia lived starting in 1937

421 S. Wabash Ave.

Occupied: 1937–1953

Housed: Radio classes, other classrooms

Trivia: Called the “narrowest in the Loop,” this building was originally used for the Veterans Administration Guidance and Research Center at Columbia and was connected by a footbridge on the fourth floor to the Fine Arts Building. It was demolished in 2010, but its façade is incorporated into the modern Roosevelt University building.

207 S. Wabash Ave.

Occupied: 1953–1963

Housed: Entire campus, including the library and a television studio

Trivia: Formerly home to the Chicago Business College, the building was razed in 1995 to expand the facilities of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra.

Al Parker: Radio Pioneer

Legendary Chicago radio announcer Al Parker was a cornerstone of Columbia’s Radio Department during his 54-year tenure at the college. A prolific broadcaster, he worked at WJJD, WIND and WLS-TV, and on a dizzying array of freelance projects.

Legendary Chicago radio announcer Al Parker was a cornerstone of Columbia’s Radio Department during his 54-year tenure at the college. A prolific broadcaster, he worked at WJJD, WIND and WLS-TV, and on a dizzying array of freelance projects.

It all started in the mid-1940s. After hearing Parker’s work, Columbia President Norman Alexandroff offered the announcer a teaching position. Parker taught one or two radio broadcasting classes a semester while he worked full time and built his reputation as one of Chicago’s most memorable broadcast voices, later becoming the voice of Chicago’s ABC-Channel 7 for 26 years.

In 1957, Parker was appointed chair of Columbia’s Radio Department. His students included Wheel of Fortune host Pat Sajak (’68); sports radio voice Chet Coppock (BA ’71); TV and radio host Bob Sirott (BA ’71); and WXRT DJs Johnny Mars (’78), Frank E. Lee (BA ’78) and Marty Lennartz (BA ’82). He hired WXRT’s Terri Hemmert, now in the National Radio Hall of Fame, as a faculty member in the 1970s. Said Hemmert: “I owe Al everything.”

Always eager to encourage his students to learn by doing, Parker helped launch WCRX, Columbia’s student-run radio station, in 1982.

Parker’s dedication to his students was as memorable as his voice, and in 1995 the college awarded him with its most prestigious honor: the President’s Medal. In 1996, Columbia established the Al Parker Scholarship to assist outstanding radio students in defraying tuition costs.

Then and Now: Workshop Method

Then: Columbia introduced the workshop method of teaching in 1947. Radio, television, advertising and journalism students worked in studio settings and created projects that mirrored what was happening in the industry.

Now: The workshop method is an integral part of nearly every discipline at Columbia. For example, Interactive Arts and Media students work in teams to create their own games from scratch; Business and Entrepreneurship classes create marketing plans for actual Chicago businesses; and Radio students use professional audio equipment to produce their own programs.